Besna Tosun has her own son now. He will likely never know his grandfather. Besna herself barely got to know him. Fehmi Tosun was detained by Turkish authorities in 1995 and disappeared when he was in custody. Her youngest sibling was only five.

Tosun is also a member of the group Cumartesi Anneleri, or Saturday Mothers. The group used to meet every Saturday in front of Galatasaray square, a busy intersection in the downtown district of Taksim in Istanbul, to protest the Turkish government’s disappearing of their family members in the 1980s and 1990s.

After the 1980 coup, the military junta ruling the country established a new constitution that allowed for state-of-emergency laws that were used liberally in the country’s Kurdish southeast territories. A post-coup crackdown on political dissidents and ensuing skirmishes with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a separatist group, placed the southeast’s Kurds, civilian and otherwise, under the state’s gaze. Hafiza Merkezi, a local human rights organization, recorded 1,353 cases of forced disappearances.

The longest-running protest in Turkey, the Saturday Mothers started meeting in 1995.

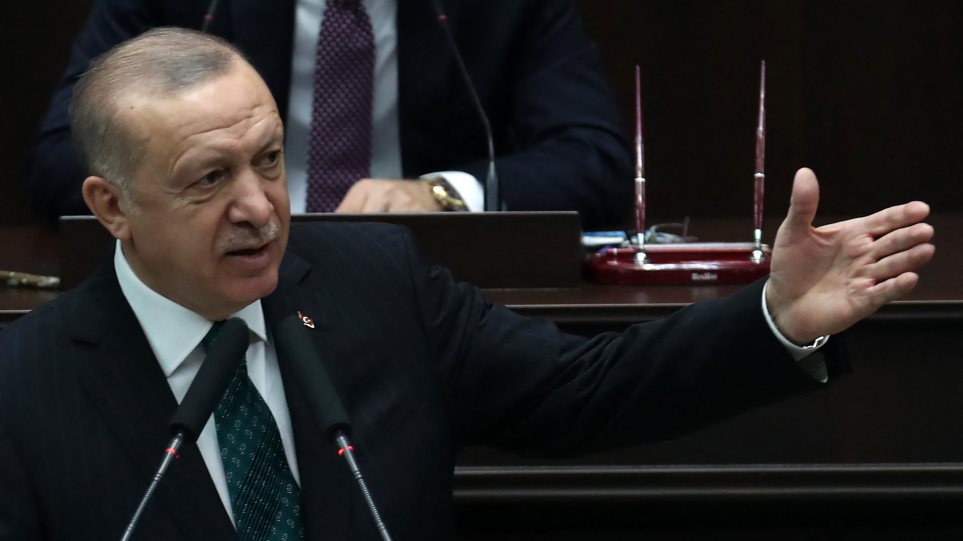

The group endured harassment, beatings, and detention, which intensified in 1998, according to an Amnesty International report at the time. Following the increased police harassment, the group took a break from weekly protests in 1999 but restarted in 2009 under Recep Tayyıp Erdoğan’s prime ministership.

Erdoğan’s initial years as prime minister were full of promises of reform and a dismantling of the privileges of Turkey’s so-called secular elites. The mothers thought a reckoning of Turkey’s past would have to include the military’s history of deposing elected governments and the violence that followed.

“In the case of these disappearances, there was simply no space for that discussion. So (the mothers) had to create these kinds of spaces to speak what was officially unrecognizable,” said Stanford University professor Kabir Tambar.

Where are Greece’s beautiful ‘fjords’? (drone video)

Grigoris Afxentiou: 64 years since the Greek Hero’s death (video)

It worked. The protests had people publicly discussing enforced disappearances by the Turkish state. Then, in August 2018, Interior Minister Süleyman Soylu barred the group from gathering ahead of their 700th meeting.

Soylu declared a link between the mothers and the PKK. Turkey and the U.S. have designated the PKK as a terrorist organization. Since the failed coup in 2016, Erdoğan and his government greatly broadened the use of the terms “terrorist” and “PKK associate.” Erdoğan’s interest in muzzling the mothers’ public presence appeared to increase as criticisms of his own government grew.

For over 800 weeks, the group’s resilience in the face of multiple states of emergency, changing governments, and Erdoğan’s dwindling concern with the appearance of democratic norms led to its latest move to create an online, accessible testament to the Turkish state’s violence.

“State violence is as old as the history of Turkey,” said Gülseren Yoleri, a lawyer and elected chair of Istanbul’s İnsan Hakları Derneği (Human Rights Association or IHD) branch. She started volunteering with the human rights nonprofit in 1991.

IHD was founded in 1986. It reports on human rights violations in Turkey and has a close relationship with the Saturday Mothers dating back to the group’s first protest.

Prior to the coronavirus pandemic and the restrictions on gathering that came with it, the Saturday Mothers were a constant on the famous İstiklal Street in Istanbul. Every Saturday, the mothers — a group that includes brothers, sisters, and other relatives — came together to protest the Turkish government’s disappearing of their family members in the ‘80s and ‘90s and its refusal to acknowledge those incidents.

Read more: New Lines