Few Europeans were guilty of assuming that new Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras would perform what Greeks call a kolotoumba (“somersault”) the instant he assumed duties, meaning to quickly change political positions.

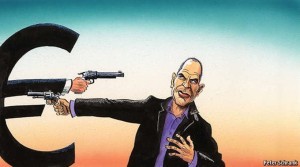

The Economist provides an extensive report entitled “Greece had a chance to make the Eurozone to work better and blew it”, on how Europe watched in a daze over the past two weeks as flamboyant Greek FinMin Yanis Varoufakis urged the Eurozone members to follow a new path.

Citing Yanis’ recent televised statements to the BBC, the media standard-bearer of the world’s liberal school refers to the former’s statement of “… the disease that we’re facing in Greece is that a problem of insolvency for five years has been treated as a problem of liquidity.”

Based on the above statement, the article explains how this view would not seem outlandish in the academic world that Varoufakis recently left, and adds: “few believe that Greece’s debts, worth over 175% of GDP, will ever be repaid in full. But saying so betrayed a woeful misunderstanding of the euro zone’s rules. If the European Central Bank shared Mr Varoufakis’s view, it would have to cut off Greek banks, potentially driving Greece out of the euro.”

Furthermore, the report continues by stressing that earlier this month, when Varoufakis visited the ECB in Frankfurt, its president, Mario Draghi, curtly told him to keep his opinion to himself. He has not repeated the mistep since.

The Economist cites what it calls Varoufakis’s gaffe as a mere footnote in a list of ‘faux paus’ that have characterized Greece’s miserable experience in the euro. But it is depressingly typical for a government that, despite its rising popularity at home, has squandered every opportunity to improve its lot, and ultimately that of the euro zone.

“Even as Mr. Varoufakis and his associates in Greece’s ruling Syriza party,” continues the article, “have loftily declared that the changes they seek would benefit all Europeans, not just Greeks, their negotiating strategy has been small-minded, self-defeating and naive.”

However, the Economist puts all the above down to inexperience. A few Europeans were guilty of assuming that Alexis Tsipras, the prime minister, would perform what Greeks call a kolotoumba (“somersault”) the instant he assumed duties.

Among others, the weekly magazine explains that Greece’s survival in the euro depends on two factors largely outside its control: the willingness of the ECB to keep supporting its banks and Eurogroup to strike a long-term financing deal.

As for a long-term deal, the Economist says that Germany and others have dangled sweeteners before Greece, including an easing of debt terms and a lower primary-surplus target. But these are prizes to be won at the end of talks, not the beginning. Syriza has already started to reverse some reforms, including privatizations and collective-bargaining rules. The Eurogroup will probably not withdraw its fiscal offers but, with trust in the Greeks at zero, the reform conditions that it will attach to a third bail-out will surely be tougher than ever.

Time is short, particularly if the Eurogroup fails to agree with Greece on the terms for a bail-out extension, adds the Economist, but continues by saying that yet an essential formula remains unchanged: that neither Greece nor its partners want to see it forced out of the euro (although the odds of an accidental “Grexit” have shortened). So at some point Mr Tsipras will have to perform his kolotoumba, potentially at high cost. At home, having raised expectations of a big win (75% of Greeks support his tough line) he might face calls for a referendum or a new election.

The article concludes by pointing out that the real Greek tragedy is that, with a bit more statesmanship, Mr. Tsipras could have nudged Europe on to a happier path. The euro zone desperately needs a counter-narrative to its failed German-inspired policy of austerity. As leader of the hardest-hit economy, armed with a strong democratic mandate, Mr. Tsipras was well placed to offer one. He could have sought allies against excessive austerity and for looser fiscal and monetary policy in places like Italy and France—and even inside the ECB. Yet by quibbling over his debt extension and backtracking so ostentatiously on sensible reform he has alienated more or less everyone. That is quite some achievement.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions