In its report, titled “Health at a Glance: Europe 2014”, the OECD has presented the most recent data on health status, risk factors to health and access to high-quality care across all EU member states and candidate countries.

The report shows that life expectancy at birth has risen in Greece to reach 80.7 years, whereas the EU average is at 79.2 years. Greece is in the 13th place, lagging behind top-ranking nations such as Spain (82.5 years). The gap between states with the highest and lowest life expectancies is at around eight years.

Life expectancy generally rose by five years on average since 1990. “Although broad measurements of health status such as life expectancy have continued to improve in nearly all EU member states, it will take some additional years to be able to fully assess the impact of the crisis on public health,” said the report.

Life expectancy has continued to increase, but inequalities persist

* Life expectancy at birth in EU member states increased by over five years between 1990 and 2012 to 79.2 years. However, the gap between the highest life expectancies (Spain, Italy and France) and the lowest (Lithuania, Latvia, Bulgaria and Romania) has not fallen since 1990.

* Life expectancy at age 65 has also increased substantially, averaging 20.4 years for women and 16.8 years for men in the EU in 2012. Life expectancy at age 65 varies by about five years between those countries with the highest life expectancies and those with the lowest.

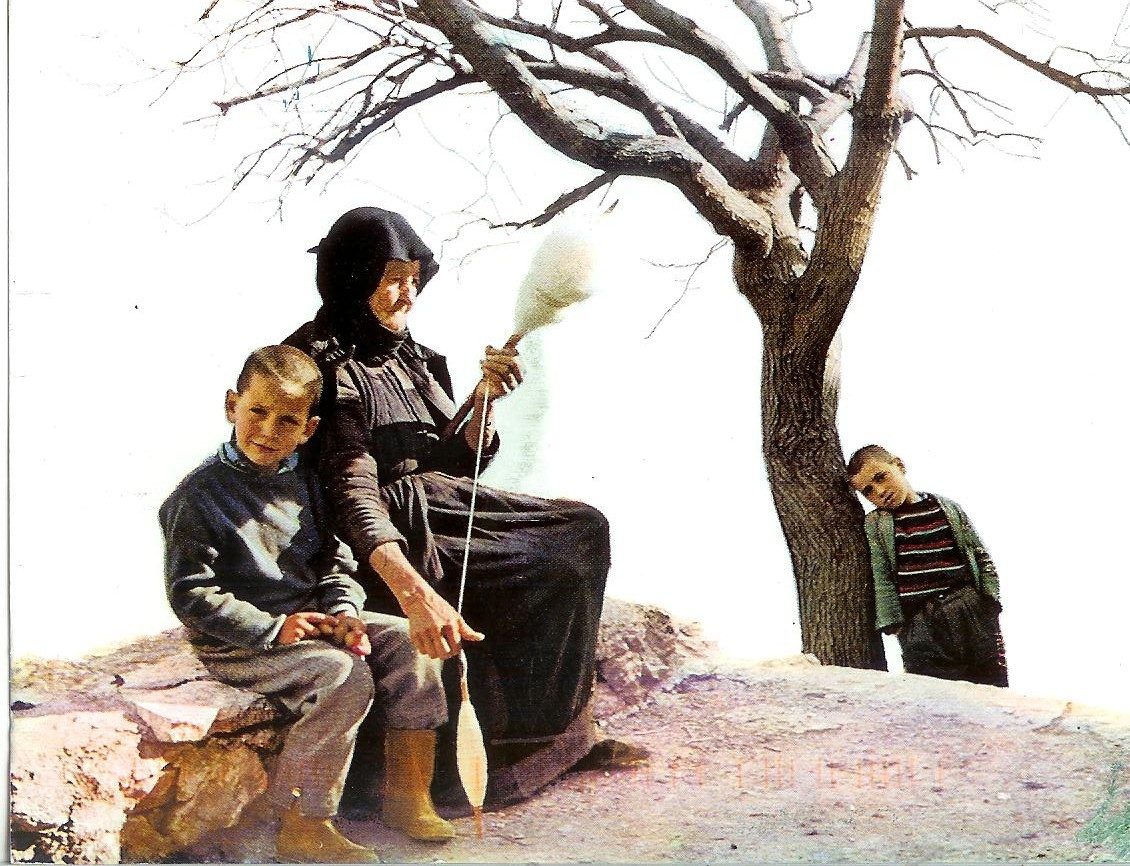

* Highly educated men and women are likely to live several years longer and to be in better health. For example, in some Central and Eastern European countries, 65-year-old men with a high level of education can expect to live four to seven years longer than those with a low education level.

* On average across EU countries, women live six years longer than men. This gender gap is one year only for healthy life years (defined as the number of years of life free of activity limitation).

Assessing the impact of the economic crisis on health

* The crisis has had a mixed impact on population health and mortality. While suicide rates increased slightly at the start of the crisis, they seem to have returned to pre-crisis levels. Mortality from transport accidents declined more rapidly in the years following the crisis than 2 in prior years. The exposure of the population to air pollution also fell following the crisis, although some air pollutants seem to have risen since then.

* The economic crisis might also have contributed to the long-term rise in obesity. One in six adults on average across EU member states was obese around 2012, up from one in eight around 2002. Evidence from some countries shows a link between financial distress and obesity: regardless of their income or wealth, people who experience periods of financial hardship are at increased risk. Obesity also tends to be more common among disadvantaged groups. Health spending has fallen or slowed following the economic crisis

* Between 2009 and 2012, expenditure on health in real terms (adjusted for inflation) fell in half of the EU countries and significantly slowed in the rest. On average, health spending decreased by 0.6% each year, compared with annual growth of 4.7% between 2000 and 2009. This was due to cuts in health workforce and salaries, reductions in fees paid to health providers, lower pharmaceutical prices, and increased patient co-payments.

* While health spending has grown at a modest rate in 2012 in several countries (including in Austria, Germany and Poland), it has continued to fall in Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain, as well as in the Czech Republic and Hungary. Universal health coverage has protected access to health care

* Most EU countries have maintained universal (or near-universal) coverage for a core set of health services, with the exception of Bulgaria, Greece and Cyprus where a significant proportion of the population is uninsured. Still, even in these countries measures have been taken to provide coverage for the uninsured.

* Ensuring effective access to health care requires the right number, mix and distribution of health care providers. The number of doctors and nurses per capita has continued to grow in nearly all European countries, although there are concerns about shortages of certain categories of doctors, such as general practitioners in rural and remote regions.

* On average across EU countries, the number of doctors per capita increased from 2.9 doctors per 1,000 population in 2000 to 3.4 in 2012. This growth was particularly rapid in Greece (mostly before the economic crisis) and in the United Kingdom (an increase of 50% between 2000 and 2012).

* In all countries, the density of doctors is greater in urban regions. Many European countries provide financial incentives to attract and retain doctors in underserved areas.

* Long waiting times for health services is an important policy issue in many European countries. There are wide variations in waiting times for non-emergency surgical interventions. Quality of care has improved in most countries, but disparities persist

* Progress in the treatment of life-threatening conditions such as heart attack, stroke and cancer has led to higher survival rates in most European countries. On average, mortality rates following hospital admissions for heart attack fell by 40% between 2000 and 2011 and for stroke by over 20%. Lower mortality rates reflect better acute care and greater access to dedicated stroke units in some countries.

* Cancer survival has improved in most countries, including cervical cancer, breast cancer and colorectal cancer. But cervical cancer survival was over 20% lower in Poland compared with Austria and Sweden, while breast cancer survival was almost 20% lower in Poland than in Sweden.

* The quality of primary care has also improved in most countries, as shown by the reduction in avoidable hospital admissions for chronic diseases such as asthma and diabetes. Still, there is room to improve primary care to further reduce costly hospital admissions.

* Population ageing will continue to increase demands on health and long-term care systems in the years ahead. The DG for Economic and Financial Affairs projected in 2012 that public spending on health care would increase by 1% to 2% of GDP on average across EU countries between 2010 and 2060, and there would be a similar growth in public spending on long-term care. Amid tight budget constraints, the challenge will be to preserve access to high-quality care for the whole population at an affordable cost.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions