Everybody knows that smoking is bad for you. After all, look at the statistics. According to the Center for Disease Control, it is responsible for 87% of lung cancer cases and one out of three cancer cases overall, resulting in circa 6 million deaths a year worldwide.

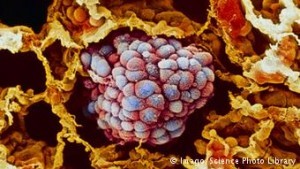

What scientists have been trying to understand is exactly how the more than 60 carcinogens in tobacco smoke manage to damage to the lungs, livers and kidneys of smokers and passive smokers.

By examining the DNA of over 3,000 tumors from the bodies of smokers and non-smokers, researchers from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and the Los Alamos National Laboratory discovered that deep molecular “signatures” were etched in tumor cells, even those never exposed directly to cigarette smoke. Their report, published this week in the journal Science, also showed how DNA has been damaged, and how each signature is a potential starting point for future cancer development.

Ludmil B. Alexandrov, a biophysicist and Oppenheimer Fellow at Los Alamos National Laboratory, and co-lead author of the study explained how they were able to identify over than 20 mutational signatures: “Different carcinogens can leave fingerprints on the genome. So what we do is we just perform a bit of molecular CSI, and we lift the fingerprints off the genome of cancers. So we are able to say based on that, what are the processes of this mutation.”

Since cells tend to mutate more as they divide and age, by increasing the number of mutations, smoking essentially ages one’s cells. Whether in smoking or non-smoking related organ cancers, smoking still accelerates a “molecular clock” that normally would “tick” regularly with age.

For those who smoke a pack of cigarettes a day, the researchers discovered that each year caused 150 extra mutations in every lung cell, each of which was a copy of the mutation. And the more mutations, the more likely the cell would become cancerous.

This ground-breaking new study could help establish “not only the complex relationship between tobacco and cancer, but also the pathogenesis of the disease from its earliest points,” points out Dr. Steven Dubinett, director of UCLA’s lung cancer research program and a professor of pulmonary and critical care medicine.

The only problem is, to quote Alexandrov: “Even if you stop smoking, these mutations are there—they are not reversible. Even if you just start smoking for a bit you will be scarred, the genetic material of your cells will be scarred for your lifetime.”

Source: Smithsonian

Ask me anything

Explore related questions