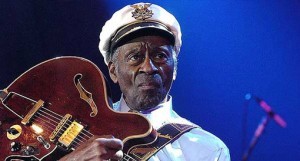

Chuck Berry, the singer, songwriter and guitar great who practically defined rock music with his impeccably twangy hits “Maybellene,” “Roll Over Beethoven,” “Memphis,” “My Ding-a-Ling” and “Sweet Little Sixteen,” has died. He was 90.

The singer/songwriter, whose classic “Johnny B. Goode” was chosen by Carl Sagan to be included on the golden record of Earth Sounds and Music launched with Voyager in 1977, died Saturday afternoon, St. Charles County Police Department confirmed. The cause of death was not revealed.

During his 60-plus years in show business, Berry in 1986 became one of the first inductees into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. He entered The Blues Foundation’s Blues Hall of Fame in ’85 and that year also received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.

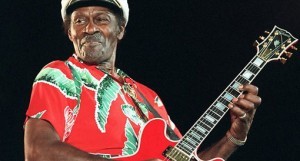

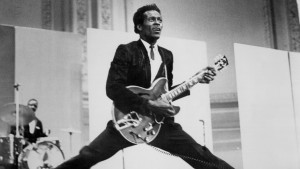

He performed in 1979 for President Jimmy Carter at the White House, landed at No. 6 on Rolling Stone’s list of the “100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time” and trademarked his stage showmanship with his famous “duck walk.”

John Lennon once said, “If you tried to give rock and roll another name, you might call it ‘Chuck Berry.’” He paved the way for such music legends as the Rolling Stones, the Beatles, the Beach Boys, the Band, Jimi Hendrix, David Bowie, Eric Clapton, AC/DC, Sex Pistols and Jerry Lee Lewis, among many others.

Muddy Waters, Berry’s idol and musical influence, gave him some constructive backstage advice: contact Leonard Chess. Chicago-based Chess Records, primarily a blues label run by Polish brothers Leonard and Phil Chess, had a series of transplanted blues artists on its roster, including Howlin’ Wolf, Bo Diddley, Jimmy Reed and John Lee Hooker.

The Chess brothers signed Berry in 1955 and produced and released his first single, “Maybellene,” an adaption of the Bob Wills song “Ida Red.” It sold more than a million copies, reached No. 1 on the Billboard R&B charts and hit No. 5 on the Pop charts, allowing Berry to build crossover appeal beyond the R&B audience.

“Maybellene” blended hillbilly licks and high-spirited blues riffs, ultimately creating the signature sound that pioneered the rock revolution. The lyrics for the song had narrative swagger, reflecting the spirit of teenage angst depicting fast cars, drag races and the story of an unfaithful girl as its main themes.

He explained his appeal to adolescents across different cultural backgrounds: “Everything I wrote about wasn’t about me but [was about] the people listening.” He had a way of identifying what people wanted to express, but weren’t able to, during this segregated time.

Berry, the fourth of six children, was born on Oct. 18, 1926, as Charles Edward Anderson. He was raised in St. Louis in a middle-class black neighborhood. His father Henry was a contractor and his mother Martha a school principal.

Berry married Themetta Suggs in 1948 and had four children with her. He supported his family by becoming a factory worker, janitor and cosmetologist before pounding the pavement in the club circuit to earn extra cash. He partnered with pianist Johnnie Johnson, joining his group Sir John’s Trio, which later became known as the Chuck Berry Combo.

His debut album, After School Session, produced by the Chess brothers, featured a variety of musicians including Johnson, Ebby Hardy, Jimmy Rogers, Willie Dixon, Otis Spann and Fred Below. The effort was tailored toward a youthful market featuring comedic cut-up lyrics, rhythmically intricate guitar parts and stand-alone solos in effortless anthems like “School Days,” “Too Much Monkey Business,” “Wee Wee Hours,” “Roll Over Beethoven” and “Thirty Days.”

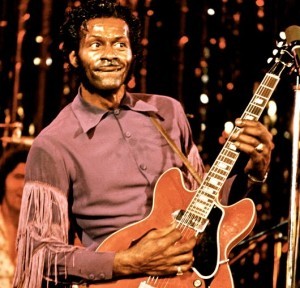

Keith Richards of the Stones, a big fan, said, “Chuck Berry always was the epitome of rhythm and blues playing, rock ’n’ roll playing. It was beautiful and effortless, and his timing was perfection. He is rhythm supreme. He plays that lovely double-string stuff, which I got down a long time ago but I’m still getting the hang of. Later I realized why he played that way — because of the sheer physical size of the guy. I mean, he makes one of those big Gibsons look like a ukulele!”

His 1972 album The London Chuck Berry Sessions, featuring a who’s who of British rock royalty went gold within a month, selling more than 500,000 copies. It featured both studio and live recordings with such songs as “Let’s Boogie,” “I Love You,” “Johnny B. Goode” and “My Ding a Ling,” a late-period hit written and first recorded by Dave Bartholomew. The novelty song about his private part became his only No. 1 pop hit on both the Billboard and U.K. pop charts.

Berry fought a number of legal situations that arised in his life. He was arrested in high school for stealing a car and robbing convenience stores. He received his GED in prison and was released at age 21. He was imprisoned under the Mann Act in the early 1960s for having sexual intercourse with a minor and in 1979 for tax evasion. He continued to make music behind bars, writing “Thirty Days,” “Nadine” and “No Particular Place to Go.”

Expressing his disagreement with the charges, “Thirty Days” included the lyrics, “If I don’t get no satisfaction from the judge/I’m gonna take it to the FBI and voice my grudge/If they don’t give me no consolation/I’m gonna take it to the United Nations/I’m gonna see that you be back home in 30 days.”

Bands like the Stones, Beach Boys (basing “Surfing U.S.A.” on his “Sweet Little Sixteen”) and Beatles covered his songs, allowing him to remain relevant to the music world, and he signed with Mercury Records in the mid-1960s. He released five albums on the label and toured on the success of his earlier hits. He quickly built a bad reputation during his live shows by hiring spur-of-the-moment backup bands, somehow thinking they’d know each lick of his music.

Bruce Springsteen and Steve Miller occasionally performed live with Berry. Springsteen and the E Street Band backed Berry during his performance of “Johnny B. Goode” and “Rock and Roll Music” at his induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Director Taylor Hackford captured Berry’s 60th birthday in the 1986 documentary Hail! Hail! Rock ‘n’ Roll, where he famously clashed with his protégé Richards. Those who appeared in the film included Diddley, Lennon, Lewis and Little Richard, all of whom revealed personal stories and relationships with him. Berry performed concerts that same year with a number of artists including Linda Ronstadt, Etta James, Julian Lennon, Robert Cray and Johnson, his original mentor.

Rolling Stone ranked his compilation album The Great Twenty-Eight as No. 21 on its list of “500 Greatest Albums of All Time,” with six of his songs included on their “500 Greatest Songs of All Time,” including “Johnny B. Goode” (No. 7), “Maybelline” (No. 18), “Roll Over Beethoven” (No. 97), “Rock and Roll Music” (No. 128), “Sweet Little Sixteen” (No. 272) and “Brown Eyed Handsome Man” (No. 374).

In 2012, Berry reported to Rolling Stone that “My singing days have passed. My voice is gone. My throat is worn. And my lungs are going fast. I think that explains it.” He continued to perform, though his shows featured little more than his trusty Gibson and those hastily assembled back-up bands.

In his 2011 autobiography, Life, Richards wrote: “The beautiful thing about Chuck Berry’s playing was it had such an effortless swing. None of this sweating and grinding away and grimacing… just pure, effortless swing, like a lion.”

Ask me anything

Explore related questions