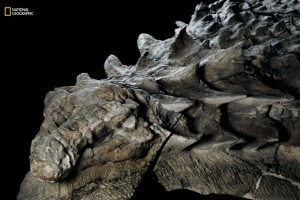

Before being assembled into something recognizable at a museum, most dinosaur fossils look to the casual observer like nothing more than common rocks. No one, however, would confuse the over 110 million-year-old nodosaur fossil for a stone.

The fossil, being unveiled today in Canada’s Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology, is so well preserved it looks like a statue.

Even more surprising might be its accidental discovery, as unveiled in the June issue of National Geographic magazine.

On March 21, 2011, Shawn Funk was digging in Alberta’s Millennium Mine with a mechanical backhoe, when he hit “something much harder than the surrounding rock.” A closer look revealed something that looked like no rock Funk had ever seen, just “row after row of sandy brown disks, each ringed in gunmetal gray stone.”

What he had found was a 2,500-pound dinosaur fossil, which was soon shipped to the museum in Alberta, where technicians scraped extraneous rock from the fossilized bone and experts examined the specimen.

(A close-up of the nodosaur fossil. The dinosaur’s head is clearly visible!)

“I couldn’t believe my eyes — it was a dinosaur,” Donald Henderson, the curator of dinosaurs at the museum, told Alberta Oil. “When we first saw the pictures we were convinced we were going to see another plesiosaur (a more commonly discovered marine reptile).”

More specifically, it was the snout-to-hips portion of a nodosaur, a “member of the heavily-armored ankylosaur subgroup,” that roamed during the Cretaceous Period, according to Smithsonian. This group of heavy herbivores, which walked on four legs, likely resembled a cross between a lizard and a lion — but covered in scales.

(A model showing how the nodosaur likely appeared)

Unlike its cousins in the ankylosaur subgroup, the nodosaur lacked a bony club at the end of its tail, instead using armor plates, thick knobs and two 20-inch spikes along its armored side for protection, according to the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History.

“These guys were like four-footed tanks,” dinosaur tracker Ray Stanford told The Washington Post in 2012.

This particular one, according to a news release, was 18 feet long and weighed around 3,000 pounds.

As Michael Greshko wrote for National Geographic, such level of preservation “is a rare as winning the lottery.” He continued:

The more I look at it, the more mind-boggling it becomes. Fossilized remnants of skin still cover the bumpy armor plates dotting the animal’s skull. Its right forefoot lies by its side, its five digits splayed upward. I can count the scales on its sole. Caleb Brown, a postdoctoral researcher at the museum, grins at my astonishment. “We don’t just have a skeleton,” he tells me later. “We have a dinosaur as it would have been.”

The reason this particular dinosaur was so well preserved is likely due to a stroke of good luck. (Well, perhaps a stroke of bad luck for the poor nodosaur.)

Researchers believe it was on a river’s edge, perhaps having a drink of water, when a flood swept it downriver.

Eventually, the land creature floated out to the sea — which the mine where it was found once was — and sank to the bottom.

There, minerals quickly “infiltrated the skin and armor and cradled its back, ensuring that the dead nodosaur would keep its true-to-life form as eons’ worth of rock piled atop it.”

That is a boon to researchers, particularly given that teeth and bone fragments are much more common finds.

“Even partially complete skeletons remain elusive,” Smithsonian reported.

(The first known example of fossilized brain tissue from a dinosaur was identified using a scanning electron microscope to peer inside a rock. Scientists say it resembles the brains of modern-day crocodiles and birds)

Ask me anything

Explore related questions