Vrasidas Karalis holds the Sir Nicholas Laurantos’ Chair in Modern Greek and Byzantine Studies at the University of Sydney. He has published extensively on Byzantine historiography, Greek political life, Greek Cinema, European cinema and contemporary political philosophy. He has edited three volumes on modern European political philosophy, especially on Martin Heidegger, Hannah Arendt and Cornelius Castoriadis. His recent publications include Realism in Greek Cinema: From the Post-War Period to the Present (2017) and A History of Greek Cinema (2013). He has also published two volumes of oral history, Recollections of Mr Manoly Lascaris (2007) and The Demons of Athens (2014), a chronicle of his experiences from Athens in the time of recent crisis.

Professor Karalis, who has been very active in promoting Modern Greek and Byzantine Studies in Australia, talks to Greek News Agenda,* stressing that Greek Cinema is one of the oldest cinematic traditions in Europe, with a big production compared to the country’s market size. He refers to Greek films that deserve more study and analysis as the foundational filmic texts of Greek cinema, such as “Daphnis and Chloe” (1931) by Orestis Laskos. He describes the Renaissance of Greek Cinema, a reversal of the cinematic traditions currently taking place, as a reflection of the deep structural incongruity between image and reality in the years before the Greek economic crisis. He also comments on the so called Greek weird wave that it is a new form that de-constructs in a way that gives new momentum to the visual tradition that started after the war.

Karalis also explores the quest for Greekness (Greek identity) throughout the History of Greek Cinema, concluding that in the new millennium Greek identity became associated with global trends, regaining a universality that transcends barriers of language and historical experience. Finally, he suggests that Greek Film studies will benefit by gender and queer studies approaches as long as they remain historically informed and underlines that his main point throughout his two books on Greek cinema is that Greek films form a continuous conversation between filmmakers and their audience, but above all between society and its historical trajectory.

(Daphnis and Chloe, Orestis Laskos, 1931)

What is the current state of Modern Greek studies in Australia? How did you decide to focus on the history of Greek cinema?

The current status of Greek studies in Australia is relatively positive. However, after the remarkable proliferation of Modern Greek departments in the 70s and 80s, a distinct decline became obvious in the early 2000s. Yet, three departments still remain strong and have a continuous impact on the academic representation of Modern Greek Studies at tertiary level. The University of Sydney, Flinders University in Adelaide and Macquarie University continue to have considerable enrollments while publishing original research and promoting Greek culture through publications, journals and conferences.

My specific focus on the history of Greek cinema emanated from the interest that our students showed for Greek films and film stars, as well as after using Greek films to teach Greek language. While literature was the preferred course during the 70s and 80, cinema became a much more attractive course for students as the language of images was a universal language which could be understood without translation. For me personally, the absence of a history of Greek cinema constituted an obvious gap in the curriculum of Greek studies.

My perception was that we needed a narrative account of how Greek cinema evolved in contrast or comparison to other cinematic traditions in the Balkans and Europe. By researching further I understood that beyond the literary achievements of Greek writers, the cinematic work of Greek directors was in many ways equal or even surpassed many filmmakers from global cinemas and needed a comprehensive, fair and accurate presentation.

(From the edge of the city, Constantinos Giannaris, 1998. Watch Giannaris film online here)

In your work you often mention that Greek film culture “deserves more recognition and credit”. Why is that? Moreover, as you conclude in ‘A History of Greek Cinema’, “In reality, many good films were produced in Greece and some of them could be safely and comfortably labeled as “great films” in the European or even global canon”. To which films are you referring?

Very few people world-wide know that Greek cinema is one of the oldest cinematic traditions in Europe. The fact that Greece was a small ‘market’ but managed to produce more than 7, 000 films indicated that the realm of images was an extremely important cultural form of expression for Greek society and a distinct socializing experience for Greek people.

Most people know for example Michael Cacoyannis’ Zorba the Greek (1964) or for more artistic audiences Theo Angelopoulos’ The Travelling Players (1975). However early films like Dimitris Gaziadis’ Astero (1929) or Orestis Laskos’ Daphnis and Chloe (1931) are films that deserve more study and analysis as the foundational filmic texts of Greek cinema. What we see in them remained one of the most enduring threads of semiotic resignification throughout the last 100 years of cinematic production.

There are also many other films whose quality and complexity stands next to the best productions of Hollywood and European cinemas. I just want to mention Michael Cacoyannis’ A Girl in Black (1956), Nikos Koundouros’ Young Aphrodites (1963) and Constantinos Giannaris’ From the Edge of the City (1997), films with their own aesthetic philosophy and visual form. Furthermore, films like Maria Plyta’s Eve (1953) or Greg Tallas’ The Barefoot Battalion (1954) even Yannis Dalianidis’ Stephania (1965) are films which deserve to be discussed for their unique organization of visual time and space. The whole oeuvre of Yorgos Tzavellas is, according to my opinion, at the same level as Jean Renoir’s and Rene Clair’s.

(Young Aphrodites, Nikos Koundouros, 1963)

You state that a Renaissance of Greek cinema is currently taking place, “which, breaking through the barriers of language and introspection, constructs a significant new chapter in the history of European and global cinema”. Is this renaissance a cultural product of the economic crisis?

I think that the renaissance started before the crisis as a crisis in representation before becoming a crisis of what was represented. The first films of what I call the ‘radical un-imagining’ of Greek cinematic tradition were those by Nikos Nikolaides, an un-imagining which in its early stages culminated with Yorgos Lanthimos’ Kinetta (2004), a film that turned Theo Angelopoulos’ Reconstruction (1970) upside down.

Also Yannis Oikonomides’ films deconstructed the language, ideology and sexuality on which the cultural complacency of the urban petit-bourgeoisie was founded. I believe that the renaissance started after the Athens Olympics in 2004 when the whole edifice of conspicuous consumption and reckless spending took monumental dimensions. A deep structural incongruity between image and reality became initially obvious and in several years disastrous. The new cinema was the consequence of a profound cultural implosion that engulfed the Greek imaginary and was crystalized around forms of disaster and catastrophe even in comedies (prime example is P.N. Koutras’ The Attack of the Giant Moussaka).

As you suggest in your work, the so-called Weird Wave that emerged after 2005 with Yorgos Lanthimos and Athina Rachel Tsangari, deconstructed all codes of representation that legitimised the dominant political order. Would you like to elaborate? What do you think about the term Weird Wave?

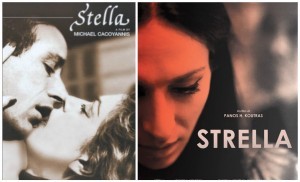

The foundations of the dominant political order were legitimized by a belief in the perenniality of Greek language, the idealization of the family institution, the myth of historical victimhood of the nation and finally of the ideology of a vital transparency in the cultural imaginary of the country. With Lanthimos, Tsangari, Panos Koutras and Costas Zappas, these pillars of self-deception were single-handedly demolished. Greek landscapes, the archetypal forms of lucidity and rationality were covered by shadows, dark secrets and incomprehensible words. The so-called ‘weird wave’ looks weird outside Greece but within the country it is what I call “the cinema of transgression.” It is a new form of representation that challenges, dismantles and demolishes. It is not destructive; it de-constructs but in a way that gives new momentum to the visual tradition that started after the war. When we realize how Stella becomes Strella we immediately see the continuity and the rupture of this new form of representation.

The quest for Greekness has been an important aspect in Greek arts and literature since the 30’s. What was its impact on Greek Cinema?

Historically, the quest for Greekness indicated lack, loss and absence, something that was the case after the Asia Minor Catastrophe. It appeared fleetingly in Astero and in some other neglected masterworks of the 30s, like The Refugee Girl. But the German Occupation and the Civil War raised new questions and defined new existential, political and stylistic quests which had more to do with class, status and power and less with history, memory or landscape. The new perception of the self emerged with Tzavellas, Gregoris Gregoriou and Cacoyannis who struggled to construct a new style for the new reality while using the underdeveloped infrastructure of small private studios. Tzavellas’ Applause (1944) is the film which re-imagined the representational codes that dominated Greek cinema with an ingenious use of montage and editing.

Following him, Gregoriou, Maria Plyta, Alekos Sakellarios and Dinos Dimopoulos established new codes of visual self-perception which later became more sophisticated and complex by directors like Roviros Mathoulis, Kostas Manousakis, Panos Glykofridis and Costas Andritsos: each one of them constructed a new style for the multiple political, sexual and class identities that emerged during the 60s. An oscillation between representational empathy and abstraction, between melodrama and critical realism offered a new impetus just around the 1967 dictatorship. The New Greek Cinema of the 1970s is the product of the immense tension between conflicting social energies, incongruous visual styles and colliding perceptions of the self.

Greekness took many forms because it represented the polymorphous diversity of desires that we find in Greek society after the 60s. In the 80s, Greekness was transformed to new perceptions of gender and sexuality whereas in the 90s expanded to the resident aliens, the immigrants. In the new millennium Greek identity became associated with global trends, discourses and codes regaining a universality that transcends barriers of language and historical experience.

In “Realism in Greek Cinema”, you mostly focus on the work of five Greek Cinema directors: Michael Cacoyannis, Nikos Koundouros, Yannis Dalianidis, Theo Angelopoulos and Antoinetta Angelidi, all representing distinct cinema styles and approaches. Which were the criteria for your choice?

First of all I wanted to map out a complete picture of cinematic production in the country. I included a chapter on Cacoyannis, as nothing was written on his complete oeuvre in English, intended to focus on his less known films, beyond Stella and Zorba the Greek. His first film Windfall in Athens (1954) for example represents a turning point to the construction of the new visual idiom that established what we call ‘national Greek cinema’. Furthermore I wanted his masterpiece Electra (1962) to be re-interpreted as his response to postwar existentialist angst as expressed by Ingmar Bergman. Electra stands on the same level both stylistically and philosophically as The Seventh Seal. And while it is true that his other films do not have the visual strength and stylistic coherence of his early creative period, his whole work represents a social commentary on the violent transformation of Greek society towards the capitalist organization of time and therefore of social relations.

The same perception was behind the chapter on the most neglected director Nikos Koundouros. Despite the fact that many critics believe that his Ogre of Athens (O Drakos) is the finest film ever made in the country nothing was also written in English on his work. Koundouros was a truth-seeker in films like The Outlaws, The River, Vortex and especially 1922: he was the first director who confronted the successive traumas of history and tried to deal with their lingering impact by transforming them into public discourse and cultural discussion. Unfortunately his work is not known outside Greece and the chapter in my book wanted to cover this gap.

Usually we ignore or denigrate the ‘commercial cinema’ of Yannis Dalianidis but in my reading I found in his films one of the most ruthless critics of the Greek petit-bourgeoisie and its ideological regimes. I insisted on the films he made during the most productive period of his career, between 1964 and 1975, when, together with his musicals and comedies, he released some of the most vicious attacks against dominant ideas about normality, sexual identity and political ideology. I think that his film The Sinners (1971), which was never released, still remains one of the most rebellious and subversive films made in the country. His film The Story of a Life (1966) is, I believe, one of the most significant feminist films ever made in the country exposing the capitalist exploitation of the female body in all classes of society.

As for Theo Angelopoulos, who is well-known, I approached him from the perspective of what I call his ‘ocular poetics.’ He was the first director who tried to teach the viewer’s eye to watch filmic images with cinematic intelligence and sensibility. Beyond his politics and his post-political melancholia, I saw him as the director who throughout his films experimented with light and color, and therefore as a major formal innovator globally. His magnificent achievement in infusing colors with emotional and self-critical content links him to the work of Kurosawa and Godard. He is one of the few global directors who succeeded in making color an integral part of cinematic iconography, with images ranging between expressionism, impressionism and hyper-realism in a surprising way transcending the obsessions of his left-wing ideological disenchantment.

Antouaneta Angelidi is also the most important film-maker in the tradition of what we call ‘experimental’ or “avant-garde cinema.’ Very few people know of the extremely complex works of Costas Sfikas, Thanasis Rentzis and many others which were produced in the country and can safely take a prominent position next to the most significant experimental films world-wide. Angelidi’s four films stand out as unique explorations of the limits of cinematic representation as well as hypnotic images foregrounding the archetypal platonic forms under the ephemerality of visual impressions.

So my purpose was to give a comprehensive account of the diversity and the complexity of filmmaking in Greece. In the introductory section of the book, I delineated the historical ruptures that made Greek cinema possible (what I call Greek visuality). Namely the discovery of perspective and the abandonment of the two-dimensional space of Byzantine iconography, the introduction of a new perception of filmic time through montage and exploration of different forms of realism in order to express the unstable realities of historical experience.

Since 1929 the dominant moods of the filmic imaginary in Greece remained those of trauma and mourning, with the relief offered by comedies also foregrounding a sense of dislocation and displacement mainly from rustic communitarianism to the anonymity of large urban centers.

(Dogtooth, Yorgos Lanthimos, 2009)

It seems that there is an increasing interest in family, gender and queer sexuality in Modern Greek studies. Which Greek cinema aspects could be viewed in this perspective?

From the first Greek film Golfo, in 1911, the central question was always about the inferior position of women in society and their peculiar representation in public discourse. Gender was at the central organizational principle of all images produced from Gaziadis to Pandelis Voulgaris – both female and male. In the beginning women were the central focus of cinematic images as innocent girls or femmes fatales, as mothers, sisters, wives or lovers. Their sexuality was always unsettling, or even threatening, as we see in most films by George Tzavellas or mischievously popularized by the only star of the industry, Aliki Vouyouklaki.

In the 70s and 80s masculinity and male sexuality were also problematized and unsettled the norms of representation. I think that ‘queer’ Greek films go back to Dalianidis’ closeted sexuality, or even further to Cacoyannis’ cryptic Eroica. Queering Greek films does not mean simply homosexualising them: it means pointing out the submerged libidinal currents that unsettled the moral certainties of dominant social groups and classes. Greek Film studies will be benefited by such approaches as long as they remain historically informed. My main point throughout my two books on Greek cinema is that Greek films form a continuous conversation between filmmakers and their audience, but above all between society and its historical trajectory.

Finally, many things remain to be discovered. Early films which believed to be lost, or films which have been neglected for various reasons. The formal aesthetics of cinematic representation in the country also needs to be explored. The lonely enigmatic figures of Takis Kanelopoulos and Stavros Tornes invite new explorations of cinematic visualities in the country.

For these reasons I believe that the importance of Greek cinema as a unique cultural achievement will increase and expand. As scholars of Greek culture in all its manifestations, we must articulate a language which will situate and interpret the achievements of Greek filmmakers in order to help other scholars to construct theoretical models and hermeneutical positions accounting for the development, form and ideology of cinematic images in Greece.

* Interview by Florentia Kiortsi

Read Vrassidas Karalis’ History of Greek Cinema [the full text] here & a book review in Filmicon Journal.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions