Didem Sen was living in Nişantaşı, a wealthy Istanbul neighbourhood mostly inhabited by members of the secular elite, when she was trying to conceive her first child at the age of 40.

She had felt the need to wait until she was married and her career was developed before trying to have a child, but fertility treatments did not work and she soon gave up.

Six years later, she says she is grateful for having missed her chance.

“At least three children you must have, before it’s too late”

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan

“I woke up this morning feeling blessed not to have [a child],” she said. “It’s a huge responsibility and a lot of work, and I worried about how my child would get a proper education in this system and what sort of future would be in store for them.”

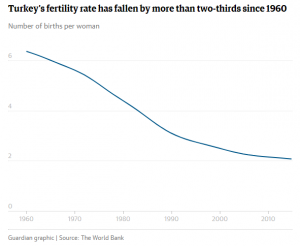

The Turkish president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, has regularly urged Turkish women to have as many as three children (most recently after the birth of his sixth grandchild, saying the country needs “bigger numbers for our population as a nation”) but underlying what many see as out-of-date, patriarchal statements is an inconvenient truth: Turkey’s population growth has stalled, and its fertility rate has declined to its lowest level since the first world war. It is also ageing.

Though Turkey remains the second most populous country in Europe after Germany, with a population of 79.5 million, and has one of the lowest median ages in Europe at 31.5 – but up from 28.8 in 2009 – figures this year from the government-run Turkish Statistical Institute showed the first time that fertility rates had dropped to the replacement rate of 2.1 in 2016.

That decline masks steeper falls in the cities but is coupled with an accelerating birth rate among refugees and rural communities that heralds the potential for major changes in the country’s demographics over the next decade.

“People in the upper social groups in Turkey have one or two children, they don’t have three or four,” said one doctor who requested anonymity. “People with larger families are in lower socio-economic groups.”

Turkey is in a dilemma that is familiar to both its Arab and European neighbours. On the one hand, a population boom without an expanding economy capable of creating jobs for young people can lead to a youth bulge and rising unemployment and marginalization – a problem facing many Middle Eastern societies. But an unchecked decline in its fertility rate would leave Turkey with an ageing population – a problem that many countries in Europe face.

“Turkey is never going to have a population of 100 million people,” said Prof Ahmet Içduygu, a sociologist from Koç University. “The policy that a bigger population means a strong country belongs to the 20th century, and we are likely to face the same problems as western countries today in 50 years.”

“Moreover, if young people don’t get a proper education and the economic system doesn’t absorb them, you will have consequences like integration problems with the refugee population, unemployment and other complications,” he added.

Figures show population growth in rural areas vastly surpassing that in the largely secular cities. While western provinces nearer Europe, such as Edirne, had birth rates as low as 1.5, the south-eastern province of Şanlıurfa, which has a high Kurdish population and half a million Syrian refugees, had a rate nearly three times as high: 4.33.

Dr Ali Enver Kurt, a gynaecologist and expert in fertility who was tapped by the municipality of Beyoğlu in Istanbul to deliver lectures and seminars to the public on fertility and in vitro fertilisation, said environmental factors such as pollution, a high smoking rate, prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases and everyday stress factors in big cities were the main reasons for infertility problems.

He estimated that 15-20% of the Turkish population suffered from difficulties conceiving, a figure that is relatively normal in developed societies.

The fall is also a symptom of Turkey’s modernity, rising education levels and improving career opportunities for women, in addition to fears over the country’s increasing polarisation. Many who delay having children, or do not have any at all, do so for a number of reasons, such as cost, the prioritization of careers, or because they do not want to raise children in a country with myriad social conflicts.

Many of the factors limiting Turkey’s population growth are common to countries in the developed world, but Turkey is particularly distinctive because of its large refugee population. It already hosts 3 million people who fled the fighting in neighbouring Syria, many of whom will be eligible for citizenship, and that number is set to increase rapidly. About 177,000 babies were born to Syrian mothers in Turkey between 2011 and 2016, with researchers at Hacettepe University estimating that 80,000 were born in 2016 with another 90,000 projected births in 2017.

“This means from now on every year 100 thousand babies will be born and this will generate 1 million more refugees in 10 years,” said Dr Murat Erdoğan, the director of Hacettepe University’s Migration and Politics Research Centre. He that if Syrian refugee families settle permanently in Turkey, it could make up for the country’s labour shortfall but also strengthen the influence of Islam in the 100-year-old secular republic. “This has aspects Turkey has to consider aside from the humanitarian side,” he said.

Source: theguardian.com

Ask me anything

Explore related questions