On the afternoon of February 9, 2011, in a suite at the City Hotel in Bucharest, two men, hoping to sell a stash of Russian military-grade weapons on the black market, met with an ebullient businessman in his sixties named Yianni. A short man with a neatly trimmed beard and a bulging midriff, Yianni was, the men had learned, a financier entrusted by the Taliban to buy armaments. As is advisable when broaching the sale of millions of dollars’ worth of illicit goods, the men—a thirtysomething Iranian-American who once worked as a translator for the U.S. Army and a Chicago-based Israeli-American in his mid-fifties—began their negotiations with caution. But after several meetings they were reassured by Yianni’s confident manner and social ease.

The men had put together a list of weapons they could supply, including FIM-92 Stingers, Javelins, and M47 Dragon missiles. At the hotel, Yianni, who spoke with a thick Greek accent, greeted them warmly. He had ordered some hot appetizers and began laying out plates and silverware on the coffee table. The Iranian-American got up to help, but Yianni waved him away: “Let me play Mama, all right?” In the next hour, the two parties settled on a price of three million dollars for the first cache, which Yianni wanted delivered to the port of Constanta, in the Black Sea. The Taliban needed the weapons urgently, he explained, to safeguard its heroin labs against American forces.

The next day, at around noon, the men met again. “You look sharp today,” Yianni said to the Israeli-American, and then explained that an advance of two hundred and fifty thousand euros was on its way. They discussed ammunition, specialists they would hire to train the Taliban in the use of the weapons, and banks to which the main deposit would be transferred. Yianni reassured the men that the BlackBerry he had given them was secure. “No, I trust you one hundred per cent,” the Iranian-American said. When Yianni’s cell phone rang, he answered: “Listen, leave the bag in the back seat, all right?” The men walked out of the suite to collect the cash.

In the hallway, they were met by a dozen Romanian policemen, their guns drawn. The men later learned, in court, that Yianni, whose real name is Spyros Enotiades, was a confidential source for the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, and that their meetings in the suite had been recorded and monitored. In 2013, the men were convicted in a U.S. federal court, each receiving a twenty-five-year prison sentence.

Sting operations are often criticized for inducing targets to commit crimes, but the D.E.A. has relied on them in its global war on drugs ever since the agency was founded, in 1973. “Nothing has been more effective than somehow penetrating a criminal organization and having an individual who can engage the organization firsthand and ideally develop evidence firsthand,” Randall Jackson, a former federal prosecutor who is now a criminal-defense attorney in a New York law firm, told me. Between 2010 and 2015, according to a Department of Justice audit released in 2016, the D.E.A. used more than eighteen thousand sources. Most of them were criminals who, in exchange for lenient sentences for their own crimes, agreed to help the D.E.A. by informing on their bosses or associates, passing on their knowledge about criminal enterprises, or collecting information from targets with whom they still had relationships. To initiate a sting operation, the D.E.A. generally asks an informant to introduce the target to an undercover D.E.A. agent or a “confidential source,” an actor for hire, who presents the target with a business opportunity that would violate American laws. If the target takes the bait, the two parties negotiate the details in meetings that the confidential source records with a device small enough to be hidden behind a shirt button. Some confidential sources are chosen for their expertise in aviation or banking, so that they can speak convincingly to targets about transporting drugs by private plane or wiring large sums of money. Some, like Enotiades, have become D.E.A. favorites.

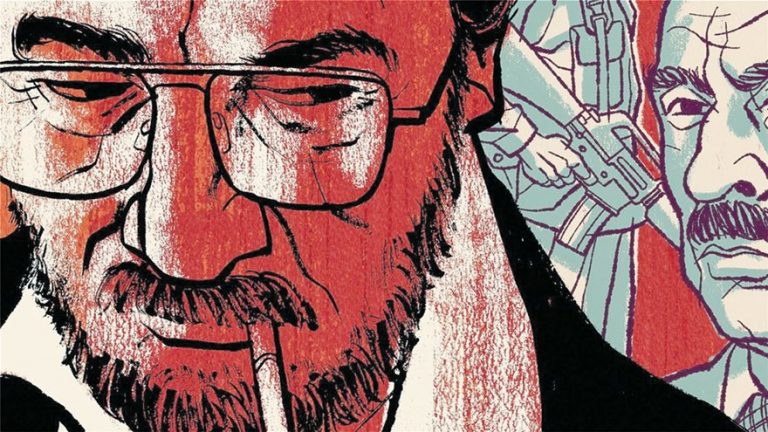

I first heard about Enotiades while reporting on a story about a D.E.A. sting conducted in Liberia in 2011, which culminated in the arrests of, among others, a Nigerian trafficker and a Russian pilot. Enotiades, who played a Lebanese financial consultant, testified at trial about his role in gathering the evidence. Listening to the recordings of his conversations with the traffickers, I was struck by how quickly he had built a rapport with them. Robert Russillo, a former D.E.A. agent who worked with Enotiades in the mid-nineties, credited Enotiades’s success to his “worldly ways” and a knack for “putting people at ease.” When Enotiades played Yianni, he took to calling the Iranian-American his “adopted son.”

Enotiades is Cypriot, with a background in pharmaceuticals and night clubs. (In addition to Greek and Lebanese roles, he has played an Italian and a Kurd.) He is in some ways an unlikely undercover operative; at seventy-two, he has suffered three strokes and has aching hips. He smokes two packs of cigarettes a day and eats with little regard for his heart condition. Recently, over lunch, his wife, a slim and genial woman named Lu Ann, asked the waiter to bring her order without the fried egg. Enotiades promptly asked that it be added to his brisket.

We met for the first time in 2015, at a restaurant in Philadelphia, and Enotiades greeted me like an old friend. A raconteur with a sharp memory who tells unlikely narratives that prove to be true, he frequently interrupts others, offering profuse apologies while doing so, and takes charge of conversations with the utmost graciousness. He is quick to express amazement or to spew expletives, often in Greek, when frustrated. This lends him an emotional transparency that gives the impression of trustworthiness. When, at a bakery in Miami, the person ahead of him was taking too long to decide what to buy, he became suddenly furious. “This is absolutely ridiculous!” he barked. “No consideration for others!” At Greek night clubs, he sings along with more passion than musicality.

Fluent in English, French, German, Italian, Spanish, and Greek, Enotiades specializes in playing the role of cartel boss, middleman, or money manager, making phone calls and holding face-to-face meetings with the D.E.A.’s targets. During the past thirty years, he has become one of the agency’s longest-serving and most successful confidential sources, participating in dozens of investigations targeting narcotics and weapons traffickers in the United States, Europe, South America, and Africa. “His ability to migrate between different types of people and cultures is incredible,” Russillo said. Louis Milione, a former supervisor in the D.E.A.’s Special Operations Division who retired last year, oversaw many of Enotiades’s operations, including the stings in Liberia and in Bucharest. “He’s got huge balls,” Milione said. “He can command a room.”

Conducting sting operations is extraordinarily dangerous. “Every little move, everything you say is being analyzed by the target,” Russillo told me. “As much as you think, This guy is just a thug, they are thinking every minute, I want to protect myself, I don’t want to get into any jeopardy.” The role-players hired by the D.E.A. receive no official training. Criminal informants are expected to know how to behave with their targets so as not to raise suspicion; confidential sources like Enotiades learn on the job. Michael Braun, who served as the D.E.A.’s chief of operations during the two-thousands, told me, “It happens routinely that you get a frigging gun pointed at your head, and somebody starts asking some tough questions, and you better not fold.” The consequences of mistakes can be dire. According to Russillo, one source who helped the D.E.A. take down several Colombian targets was found in Miami with a “Colombian necktie”—his tongue pulled through a slit in his throat.

Until the late eighties, D.E.A. agents usually did undercover work themselves. Michael Levine, a former agent who has written books about his undercover experiences in Central and South America during the seventies and eighties, told me, “We played Russian roulette with our lives.” Starting in the early nineties, the agency increasingly assigned those roles to outsiders. Milione confirmed that the D.E.A. was inclined to hire confidential sources in situations where supervisors did not want to endanger the life of an agent. “It could be too risky,” he said. At the same time, he added, “it’s not like we consider the sources disposable.” The D.E.A. is equally invested in protecting all undercover role-players, whether sources or agents, he said. Some argue that outsourcing such work to freelancers could lead to unethical practices. “How do you protect their safety and security?” Cyrille Fijnaut, a retired law professor and expert in comparative criminal law, asked. “You always have the practical issue: how can you insure that you will not run into an entrapment scenario?” (A spokesman for the D.E.A. denied that risk motivates its use of confidential sources, and said that the D.E.A. prefers to use agents “in as many investigations as possible.”)

Confidential sources can be handsomely rewarded. A former drug dealer named Carlos Sagastume, who played a member of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or farc, in a sting that led to the capture, in 2008, of the arms trafficker Viktor Bout, was given seven and a half million dollars for his work on two cases. Enotiades received a paltry income from the D.E.A. until around 2003. Since then, he has earned more than six million dollars, including two million for the sting in Liberia. When he was starting out, he said, he seldom thought about the money: “Every time I was called to play an undercover role, I felt like I was being invited to a game of chess or backgammon that I wanted to win.”

When posing as a drug trafficker or a money launderer, Enotiades thinks of himself as a businessman. He told me that he draws upon his memories of accompanying his father, Harris, a pharmaceuticals distributor in Cyprus, to lunch meetings with company executives. “If you ask me to play the role of a street guy, I will fail,” he said. The key is to present his assumed identity as a self-evident truth. “If you were a drug dealer, you’d be sitting here because you believe that I can satisfy your needs,” he said. “If you don’t believe it, my attitude is, You can go the hell out of here and find someone else. I don’t need you. Who are you to doubt me? Why do I have to prove myself to you? Show me ten thousand kilos of coke right now if you are such a big shit. Where is it? Let’s go and see.” When he was younger, Enotiades sometimes had to raise his voice or slam his fist on the table to gain control of a meeting. “Now I say, ‘Please don’t make me angry,’ ” he said. “Instead of shouting, I lower my voice so that people have to bend over to hear what I’m saying. It has a stronger effect.”

Enotiades and his three siblings, Stephanie, Christis, and Marina, grew up in a wealthy family in Nicosia, at a time when Cyprus was a British colony. E.O.K.A., the National Organization of Cypriot Fighters, was growing in popularity, and when Enotiades was eleven he began helping to distribute flyers. “What I learned from there as a child was secrecy and loyalty,” he said. “These things are not negotiable.” At twelve, he transported a pistol for E.O.K.A. across Nicosia and, at thirteen, was interrogated by the police following a demonstration. It was then that his father sent him off to a French Catholic boarding school in Athens. At night, he and his friends sneaked out to bars, night clubs, and brothels.

After Cyprus gained its independence, in 1960, Enotiades did a stint in the Cypriot Army, then studied business administration at the Northwestern Polytechnic, in London. He had never much liked drinking and, at twenty, after smoking hash, developed an aversion to drugs. “I decided I want my senses in full performance at all times,” he recalled. But he loved night life, and an uncle taught him how to gamble. After graduating, in 1968, he spent time in France, Germany, and Austria, and worked briefly as a sales manager for Johnson & Johnson. In the mid-seventies, he moved to Rhodesia, where he started a company importing pharmaceuticals, and returned to Cyprus in 1980, to join his father’s company.

One evening in 1982, his father mentioned that a Cypriot pharmacist based in Johannesburg had approached him to buy twenty thousand tablets of the amphetamine Captagon, which was manufactured by the German company Chemiewerk Homburg. The pharmacist wanted Enotiades’s father to relabel the drug, apparently to save on customs charges when the tablets were exported to South Africa. Enotiades consulted a friend, Panicos Hadjiloizou, the head of the narcotics squad in the Cyprus Police Department, who told him that the medication was widely abused as a narcotic. Hadjiloizou, who now manages a private-investigations firm in Nicosia, recently recalled telling Enotiades that reporting the scheme to him was the right move; his father could have ended up in prison. Directed by Hadjiloizou, Enotiades asked the buyer to meet him in Frankfurt, to supervise the shipping to Johannesburg. When the man showed up, he was arrested by the German federal police. “I felt as though someone had lifted a huge rock from my shoulders,” Enotiades said.

Enotiades’s association with the D.E.A. began in 1988. Intent on forging his own path, he had moved to Buenos Aires to start a business exporting beef to the United States. There he befriended a Greek taxi-driver named Stavros, who, he later learned, was a drug dealer. One day, Stavros asked Enotiades if he would help locate buyers of cocaine in the United States. “I thought, I must be jinxed,” Enotiades said. “They tried to do this to my father, now they are trying to do this to me.”

Again, Enotiades sought advice from Hadjiloizou, who cautioned him against going to the local police, because he feared that they were corrupt, and directed him instead to D.E.A. agents at the U.S. Embassy in Buenos Aires. The D.E.A. signed Enotiades up as a source on the case, asking him to accompany Stavros to Panama to meet with dealers. Enotiades’s job was to convince the dealers that he could organize the delivery of barrels of acetone—used in the manufacture of cocaine—in exchange for the drug. This meant gaining their trust. “We were literally together 24/7,” he said. The targets took him to strip clubs and to a party at a private residence where Panama’s military dictator, Manuel Noriega, made a cameo appearance. One day, Enotiades invited one of the Panamanians to his hotel room, where the target noticed his passport on a table and discovered that Enotiades wasn’t Greek, as he’d claimed. The target took the passport and informed his associates. “I was really paranoid,” Enotiades recalled. He left the hotel and went to the case agents, who pressured local authorities to retrieve his passport from the target. Within hours, Enotiades was on a flight out of Panama, having left his bags behind. “I’m lucky they didn’t kill me,” he said.

Enotiades was exhilarated by the danger and the thrill of manipulating criminals: “Once you get into this and you’re hooked, you’re hooked.” He began looking for drug dealers in the night clubs and casinos that he frequented in Buenos Aires, sometimes by dropping hints that he was a dealer himself. In 1991, he moved to Brussels with a plan to start a business importing aluminum from Russia and exporting Argentine beef there. He began dating a restaurant owner, Mary, whose brother knew a Greek businessman and night-club owner named Nicos Tsakalakis. Mary’s brother told Enotiades that Tsakalakis was in the drug trade. One night at his club, Tsakalakis, a skinny, nervous man in his early thirties, invited Enotiades to his office, where he cut and snorted heroin and offered some to Enotiades, who politely declined. “I say, ‘When I drink, I don’t,’ ” Enotiades recalled. Tsakalakis claimed to have the best heroin from Afghanistan, and asked whether Enotiades could find a distributor in the United States. Enotiades replied noncommittally, but got in touch with an agent in the D.E.A.’s office in Brussels. (The agent, J., who asked that his full name not be used, is now retired from the D.E.A.) Enotiades told him about Tsakalakis, and J., after contacting the Belgian police, discovered that they had been pursuing him for years.

Under J.’s direction, Enotiades informed Tsakalakis that he had spoken to contacts in Boston and could attempt to broker a deal for about fifty kilos. Tsakalakis quoted a price, and later took Enotiades to Amsterdam, where he introduced him to his partner, Gerard Raven, a stocky Dutchman who was about fifty years old. Raven took a liking to Enotiades’s new Alfa Romeo, and suggested that they make a trade. Enotiades, sensing that Raven was testing him, agreed. (He claims that he did so at J.’s suggestion; J. says that it was Enotiades’s idea.) Soon afterward, Tsakalakis told Enotiades that Raven and another partner would accompany him to meet with the buyers.

In early 1993, Enotiades travelled with the men to Boston, where, according to Enotiades, the D.E.A. had booked four suites at the Swissôtel in the financial district. Two undercover agents, acting as his buyers, greeted him with feigned familiarity and took the visitors out to expensive restaurants, leaving extravagant tips in the style of moneyed mobsters. One afternoon, the agents picked up the four men from the hotel and drove them to a bank, where a manager escorted the men into a vault in the back, its walls lined with metal drawers. One of the agents unlocked a drawer and pulled it out. It was packed with bundles of hundred-dollar bills. As Enotiades recalls, the manager told the men, “This one is earmarked for you.” (One of the two undercover agents, who now works in the private sector, confirmed the sting, including the “flash roll” at the bank.

Tsakalakis said that they would get everything ready for delivery when they returned to Brussels. Enotiades had completed his assignment, and the investigation proceeded without him. In 1995, the three men were indicted in federal district court in Boston on charges of conspiring to import heroin into the United States. Extradited to the U.S., they pleaded guilty and received sentences ranging from six to nine years.

One of Enotiades favorite stories is the ancient Greek legend of Damon and Pythias, in which Damon offers himself as a hostage to the tyrannical king Dionysus I, so that his friend Pythias, who has been sentenced to death for plotting against the King, may visit his family to say goodbye. The King agrees, not expecting Pythias to return, but he does. Moved by the friends’ mutual trust, the King grants them both their freedom. “Friendship is not just a word,” Enotiades said. “It is a philosophy.” He claimed to see no contradiction between his avowal of loyalty toward friends and his betrayal of the targets whom he befriended: “When I work, I feel like an extension of law enforcement. I don’t feel like a snitch. I am like any other agent who might be doing an undercover job.” Ultimately, his deceptions rely in large part on the greed of the drug dealers and arms traffickers with whom he has negotiated. “They want to believe in me because they are preposterously narcissistic, and they believe they can get anything they want,” he said. “They have these people around them kissing their feet all day long. They believe that I am a friend of theirs. I am like a rope, a long piece of rope. They grab that rope and they put it around themselves till they get hanged, because they are in this dirty business. I feel sorry for them, but they know what they’re doing.” Yet there have been times when he has felt uneasy about the fate awaiting a target. He almost admired Konstantin Yaroshenko, the pilot in the Liberian sting, because he spoke so fondly of his wife and daughter. If Yaroshenko had ever wanted to pull out of the deal the two had struck, Enotiades said, “I would have fought tooth and nail to protect him.”

Enotiades’s business ventures and personal relationships have often suffered because of his work with the D.E.A. After the case in Brussels ended, so did his relationship with Mary. “Everybody found out,” he said. “If I had gone back to Brussels, Tsakalakis’s friends would have chopped me to pieces.” The D.E.A. advised Enotiades to move to Detroit, where he rented an apartment, and the agency paid him nine hundred dollars a week to collect intelligence on the city’s drug traffickers. (The agency arranged for his U.S. visa, which, according to Enotiades, has been renewed every six months for more than a decade.) He became romantically involved with a Greek singer named Elena, and, in early 1994, frustrated that none of his leads were developing into major cases, he moved with her back to Buenos Aires, to open a Greek night club, First Class. He saw it as a business venture, one that would allow him to indulge his love of night life while also, he hoped, giving him opportunities to identify potential targets.

Looking for help in protecting the club, he befriended an Armenian-Argentine named Agop, who had contacts in the local police department. Enotiades learned that Agop worked for cocaine traffickers related to leaders of Colombia’s Medellín cartel, the Ochoa brothers, who were in prison. Under the direction of D.E.A. agents in Buenos Aires, Enotiades claimed that he knew distributors in the United States who were interested in buying bulk quantities of cocaine.

Orchestrating a sting is like staging a play, one with a script flexible enough to accommodate the words and actions of the oblivious key antagonist. Louis Milione, Enotiades’s former supervisor, told me that he and his team would draw flowcharts simulating the various ways in which a meeting could proceed. “You have to anticipate—O.K., if the target comes up with a proposal, this is our response,” he said. “If the target goes in this direction, you take it in this direction.” The undercover source mustn’t make any promises that he can’t keep, such as committing to arranging for a safe house to store drugs at a transit point. “We have to live with the lie that we create,” Milione said. “So if we put something out there that we say we can do, and then it’s time to do it and we can’t do it, that might be enough to create suspicion.”

Enotiades has enjoyed collaborating with the agents, although he hasn’t always agreed with their directives. Sometimes, he said, “I say no. I do what I feel I can do well. You have to be able to go by intuition. If it rains, you take an umbrella.” The D.E.A. attempts to minimize risks in a sting—by monitoring meetings as closely as possible, using distress signals and code phrases—but the most ambitious operations involve multiple parties and locations, and targets’ responses are harder to predict. In the summer of 1994, Enotiades flew to Salta, in northern Argentina, to meet with two traffickers, Luis and Miguel, who had agreed to supply ten thousand kilos of cocaine to the American buyers whom Enotiades claimed to represent. Before finalizing the deal, however, the cartel members wanted to meet the buyers face to face. The D.E.A. began working on a plan to have undercover agents play the American buyers, but the traffickers grew impatient, and on Thanksgiving Day Luis, Miguel, and another cartel member flew to Buenos Aires in a private plane.

Agop had warned Enotiades of the visit, but D.E.A. agents at the U.S. Embassy were on Thanksgiving break and weren’t responding to messages. When the traffickers arrived, Enotiades tried to explain that he had no control over the buyers’ whereabouts. But the men insisted on driving him to the airport. As they boarded an eight-seater turboprop, one of them took his passport.

Enotiades quickly realized his mistake. “What I should have done, knowing what I know today, I would have disappeared until I was able to get in contact with the controlling agents and get direction from them,” he told me. The plane made a stop in Salta. Enotiades recalled, “I said, ‘Listen, I know you don’t understand it, but, by the same token that I wouldn’t be able to find any of you over Christmas, I can’t find anybody over there.’ ” Instructed to keep trying to reach the buyers, Enotiades called Bill Weinman, a D.E.A. contact in Detroit, hoping to convey his predicament without drawing suspicion, but there was no response. The plane took off again, and finally landed on a dirt runway in the middle of flat grassland. As Enotiades got off, he saw guards with assault rifles idling in front of a large barn. One of them handed him a phone, and asked him again to call the buyers in the United States. Enotiades tried Weinman again, to no avail. His hosts ushered him into the barn, where piles of cocaine, compressed and packaged in plastic wrapping, were stacked on wooden pallets, and gave him the phone, explaining that, if the buyers were not in Buenos Aires the next day, there would be trouble. Enotiades, who knew that the agents would likely not be at their desks until after the Thanksgiving weekend, left Weinman a string of voice mails. Weinman, who has since retired, recalled the panic in Enotiades’s voice.

Enotiades sat by the door inside the barn, listening to the guards talking about him—he recalls the phrases “son-of-a-bitch liar” and “dead meat”—as they cooked beef on a grill. Someone brought him a blanket, then locked the door for the night. After his eyes adjusted to the darkness, Enotiades found a spot where he thought he could feel a breeze passing beneath the wall of the barn. He began to move bricks of cocaine from one of the pallets, and then, using a plank, dug a hole in the dirt floor. Eventually, he began to claw out the dirt with his hands. “I started hurting, I really started hurting, and I didn’t know what to do,” Enotiades said, recalling that he tore open a brick of cocaine and covered his injured hands with the plastic, so that he could keep digging. Early the next morning, he squeezed under the wall, and then ran until he reached a dirt road, where a pickup truck gave him a ride to the nearest city, Clorinda, near Argentina’s border with Paraguay. He was so scraped and muddied that he recalls having to persuade the driver not to take him to a hospital. Instead, he contacted a friend, who took him to the U.S. Embassy in Asunción, and then on to São Paulo, Brazil, where D.E.A. agents got him a new U.S. visa. On Christmas Eve, a month after his ordeal began, he flew into New York City. Russillo, the D.E.A. agent, who helped him get settled in New York, told me that among the first things Enotiades needed were shoes and a winter coat, since he’d left South America in flip-flops and a shirt.

The D.E.A. won’t disclose how many sources have come to harm because of their work for the agency, but a 2015 audit by the Department of Justice found seventeen cases in which federal benefits were being paid either to the families of sources who had been killed or to sources who had been disabled. The report noted that the procedures for determining eligibility for such benefits were vague and inconsistent. It is possible that the number of people who have died or suffered injuries while working for the D.E.A. is higher.

Enotiades believes that the D.E.A. was negligent in not insuring that he had a means of getting in touch over the holidays. But, he said, “it was a bigger fuckup on my part that I thought I would be able to handle it by myself.” (A spokesman for the D.E.A. declined to discuss the case or “the specifics of any past or present D.E.A. confidential source’s involvement with D.E.A. investigations.”) The terrifying experience reminded him of how many losses he’d incurred on the job—once again, he was forced to abandon his home, his business, and his girlfriend. (Elena, like many of Enotiades’s friends, learned about his work only after news of the Liberian sting became public, and never knew why he had left Brussels. “I was very upset with him . . . too many lies,” she wrote to me. “Til today I don’t know what is true, what is a lie.”) Enotiades reminded me that, in 2011, after the Liberian sting, another D.E.A. confidential source who worked with him, a pilot who had a business registering airplanes in Malta, had been forced to go into hiding. The man, who preferred that I not use his name, told me, “My girlfriend of ten years had no idea what I was doing until that court case came out.” The relationship ended and the man closed down his business and moved elsewhere in Europe, where he has continued to work with the D.E.A.

In 1995, Enotiades started a telecommunications business and a construction company in New York with friends. Both had closed by 1999, in part because Enotiades had spent most of his time working for the D.E.A., investigating dealers within the Greek community in Queens. “If you want to do this job right, you have to do it full time,” he told me, adding that D.E.A. agents had always praised him for his willingness to quickly prepare for a new operation. Enotiades’s younger brother, Christis, who works in finance in Nicosia, told me that he used to worry whenever Enotiades was out of touch for more than a few days. Then, in 1999, Enotiades’s father visited New York, and Enotiades introduced him to Russillo, his main contact at the D.E.A., and explained what he did. Enotiades recalled, “I wanted my family to at least know that, hey, if something happens to me, you shouldn’t be ashamed. What happened to me wasn’t because I was on the wrong side.”

In 1999, Enotiades met Lu Ann on a flight to Las Vegas, where she was moving to work as a kitchen designer. He flew to Las Vegas every two weeks to spend time with her. She knew him only as a businessman, but, after he failed to contact her for three weeks because he was on an assignment, he was forced to tell her that he worked for the D.E.A. (“I didn’t know what she would think,” Enotiades recalled. “I said something like ‘Because I speak many languages, I work as a consultant, as an interpreter.’ You make it sound as clean as possible.”) Lu Ann still had her doubts about his profession when, four months after meeting, they got married. Soon afterward, agents from the D.E.A.’s Las Vegas office called him, asking to meet in the parking lot of a Walgreens so that they could hand him a recording device. She drove him there, and saw two men dressed in suits and white shirts waiting for him. “I was, like, Well, it’s got to be true,” she recalled. “Who else would be dressed like that in Las Vegas in the middle of the night?”

In October, 2001, Enotiades and Lu Ann moved to Dallas and opened an outlet for designer kitchens. But, Lu Ann told me, undercover work “was always more exciting to him than having a brick-and-mortar place.” It was years before she understood the nature of his work and his relationship with it. “He’s visionary in finding an opportunity, but making a business out of it is not something that Spyros’s personality is suited to, on a day to day,” she said. “Anything that requires routine, being steadfast—none of those things really work for Spyros.”

Until the early two-thousands, Enotiades had played mainly mid-ranking members of drug-trafficking organizations or the underling of a cartel boss. As he neared sixty, his roles began to change. In September, 2004, agents from the D.E.A.’s Special Operations Division brought Enotiades into an investigation targeting a Colombian cocaine trafficker named José María Corredor Ibagué, who went by the nickname Boyaco. He was thought to have close links to farc, which the U.S. government considered to be a terrorist organization. The D.E.A. assigned Enotiades to play a kingpin named El Ruso, based in Argentina, who supplied cocaine to several countries, transporting the drugs using a personal fleet of cargo ships.

Enotiades prepares for the roles he’s assigned through research and often by repeating the name of the character he’s about to play while he’s in the shower, “getting rid of any thoughts that have nothing to do with the case.” He obsesses over little things: the deodorant he wears to conceal the smell of his fear, whether to gel his hair, “whether I should have the look of a banker or look so casual as to convey that I don’t care about my appearance.” He once bought a four-thousand-five-hundred-dollar Corum sailing watch for a meeting with a target on a yacht. “Sometimes you wear an expensive suit, and you let the label show—there are ways of doing it—and they think, Fuck, he is wearing a two-thousand-dollar suit! Even if you bought it for three hundred dollars.” To play El Ruso, he wore a stylish sports coat and expensive shoes. On the evening of September 20, 2004, Boyaco, a short man who carried himself with an exaggerated air of authority, came to see Enotiades at the Tamanaco InterContinental, a luxury hotel in Caracas, Venezuela, with three men, one of whom he introduced as Sandro, a pilot.

The men had a drink at the bar, and then walked to a patio by the hotel’s swimming pool, where everybody ordered drinks and food. D., a D.E.A. agent who worked on the investigation, told me that he and other agents were monitoring the meeting through binoculars from a hotel room with a poolside view. Venezuelan law-enforcement officers, dressed in plain clothes, were scattered throughout the property; some sipped drinks at a table close to where Enotiades and his guests sat. Despite the security, the D.E.A. had decided that it wouldn’t be safe for Enotiades to wear a wire. “Just in case they patted him down or insisted that he lift his shirt,” D. explained.

After some introductory conversation, Enotiades told Boyaco that he was looking for a new supplier. Boyaco and his partners would have to commit to whatever price was agreed on, he said, even if the market price went down. When one of Boyaco’s men objected, Enotiades got up as if to leave. Boyaco beckoned to him to sit down, and rebuked the man for speaking out of turn. Enotiades said that he would buy five thousand kilograms of cocaine at five thousand dollars per kilogram, and would pay seventy per cent for the first thousand kilograms in advance. He wanted the cocaine packaged in plastic and stamped with an “R,” for “Ruso.” Boyaco offered another thousand kilos on credit, but Enotiades said they needed to establish trust with a first purchase. The snub seemed to convince Boyaco that their relationship was worth cultivating.

Three hours later, the agents were delighted by what they saw from the hotel room. “They walked out arms locked, like they knew each other for fifty years, hugging and patting each other,” D. told me, adding that the agents could tell from the body language that Boyaco would be willing to meet again. At Enotiades’s invitation, Boyaco agreed to return to the Tamanaco for a follow-up meeting on October 1st. That evening, shortly after Boyaco and his two associates arrived at the hotel bar, where Enotiades was waiting, the three men were arrested by the Venezuelan National Guard. The cops maintained Enotiades’s cover by handcuffing him and marching him out of sight.

Boyaco escaped from a Venezuelan prison in 2005, and was recaptured in Colombia before being extradited to the United States in 2008. Federal prosecutors confronted him with evidence that the D.E.A. had collected, including an affidavit by Enotiades detailing the meeting at the Tamanaco InterContinental. Among other charges, Boyaco pleaded guilty to one count of narco-terrorism, becoming the first person to be convicted under a new federal statute, enacted in 2006, to combat what the U.S. government views as a growing nexus between drug crimes and terrorist activity. In 2012, the State Department paid Enotiades five hundred thousand dollars for his role in the operation. To celebrate, he bought an African gray parrot and named it Boyaco.

When we began talking, in 2015, Enotiades told me that he planned to retire soon, and that was why he felt comfortable sharing his story. He was keen to get recognition for the work he had been doing, even though he was aware of the risks of drawing attention to himself. He sometimes seemed bitter about the difficulties of working with the D.E.A., whose larger payments can take years to materialize, he said. He needed daily medication for his heart and his hips, and had no health insurance. But it struck me that it was Enotiades’s other ventures, in which he had invested his earnings, that had more often failed him. The kitchen outlet in Dallas had closed in 2009, forcing him and Lu Ann to sell their house and move into an apartment owned by a friend. Enotiades had no choice other than to keep working, but he remained upbeat. “If I had the money, what would I do? Sit by a beach somewhere?” he said. “That’s not my style.”

He seemed not to lack assignments, flying off on short notice to the Bahamas, Panama, and Moldova to meet with targets. One afternoon, as we talked on Skype, he answered a call from a drug trafficker in California who had been released from prison. Enotiades adopted a gruff and dismissive tone. The trafficker knew him as Ross, a major distributor of drugs in the United States, and was looking to supply both heroin and meth. After a brief conversation in Spanish, Enotiades hung up and turned to me, beaming. “Thank you, you brought me good luck!” he said. A moment later, an agent called from a field office. She had been monitoring his exchange with the target, and asked Enotiades if he knew what she liked most about the conversation.

“What did you like about that conversation?” Enotiades asked with a laugh.

“He said himself that he could hear you,” the agent said; Enotiades had apparently pretended that the line was bad. Having those words on the recording meant that it would be more valuable as evidence if the investigation culminated in a prosecution.

The agent had heard everything, too, but Enotiades summarized what the trafficker had agreed to. “We can have up to twenty kilos of heroin,” he said. “I specified the quantity for the meth because I’d told him that I wasn’t working in meth, and I didn’t all of a sudden want big quantities of meth. And he said clearly, ‘Whatever quantity you want.’ ” That, in Enotiades’s view, was the unambiguously incriminating utterance that would prove the target’s guilt in court.

Source: newyorker

Ask me anything

Explore related questions