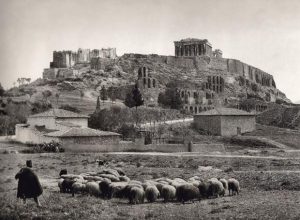

When Athens was officially declared the capital of the newly established Greek State on September 18, 1834, it was a small village of 7,000 residents living around the Acropolis Hill.

Following the assassination of Governor Ioannis Kapodistrias in the Peloponnesian city in 1831, Greece’s first politicians had to decide where the new government and first parliament would be established. At the time, Athens was an area of ancient, Byzantine and medieval ruins with makeshift houses around them, all around the Acropolis Hill.

The decision was far from easy. Personalities of the time, politicians, as well as architects and city planners took part in the debate, trying to influence developments and the final decision. The cities proposed were, among others, Corinth, Megara, Piraeus, Argos, as well as Nafplio again.

Eventually, Athens won the race and in September 18, 1834 it was officially proclaimed “Royal Seat and Capital”. The main reason was the city’s glorious history as the cradle of Hellenic Civilization. According to historians King of Bavaria Ludwig I was influential to the decision as he was a great admirer of ancient Greece.

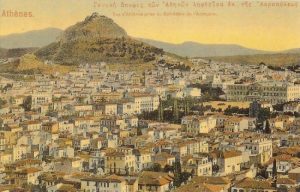

(Athens circa 1890)

However, the city was not prepared to carry the weight of the capital of the new state. It was more of a town than a city, with 7,000 residents and 170 regular houses, as the remaining Athenians were living in huts. Furthermore, the battles that took place in Athens had left many ruins. By comparison, at the time, the population of Patras amounted to 15,000 thousand, while Thessaloniki had 60,000.

Athens stretched around the Acropolis (from Psiri to Makrygianni), having as its center the area of Plaka (the Old Town). One of the major problems of the new capital was the lack of a water supply system, as well as the absence of public lighting and transport, while there was a complete lack of social services.

Greece’s first king, Otto of Bavaria, commissioned the reconstruction of the devastated city to Greek architect Stamatis Kleanthis and the Bavarian Leo von Klenze with a strict order not to damage the archaeological sites. For the protection of antiquities, Otto issued a decree prohibiting the construction of limestone at a distance of 2,500 meters from ancient Greek ruins, so that antiquities could not be damaged.

Within four years, about 1,000 houses were built in Athens, many of them makeshift, with no architectural or street plan. Otto banned quarrying in the hills of Nymphs, Achanthos (Strefi), Philopappou and Lycabettus and issued decrees with the strict order to immediately demolish every house built near archaeological sites and everything built on the outskirts of the Acropolis Hill.

The strict measures regarding building houses made Otto lose his popularity with the poor masses, but he insisted on issuing other decrees.

In the years to come, Athens became the pole of attraction for Greeks, who arrived in the capital from all parts of the country. In 1896, Greece hosted the first modern Olympic Games. By that time, the picture of the capital was radically changed. It had expanded and now was a city of 140,000 residents with great buildings and important archeological sites, and the commercial and cultural intellectual center of the country. A true capital.

Source: Philip Chrysopoulos/greekreporter

Ask me anything

Explore related questions