PASOK celebrates 50 years of existence today, having been founded by Andreas Papandreou on September 3rd at the Capital Hotel in Syntagma. Protothema.gr marks this anniversary with five articles by Pantelis Kapsis, Nikos Felekis, Dimitris Pagadakis, Dimitris Danikas, and Stefanos Tzanakis.

Until 2012, when SYRIZA overtook it in the elections, PASOK was one of the main pillars of Greece’s post-junta political system, governing alone or in coalitions for 23 of the 50 years of this era. It played a leading role in several landmark reforms that transformed Greece across various fields.

Today, PASOK faces a leadership election, not regaining its second place in the European elections. Despite significantly narrowing the gap with SYRIZA, it remained in third place under the leadership of Nikos Androulakis. The anniversary of September 3rd offers a moment for reflection not just on the past but also on the future.

Pantelis Kapsis: Half a century later

Much has been written about the causes of PASOK’s decline. Yet, while it is important to discuss the party’s 50-year history, it is perhaps more relevant to explore the reasons behind its political dominance for much of the post-junta era. Why did it come to be seen as the natural party of power for a time? These factors are still relevant today, and recognizing them might benefit those who aspire to inherit its legacy. Some of these reasons are obvious but often forgotten, while others have gone unnoticed.

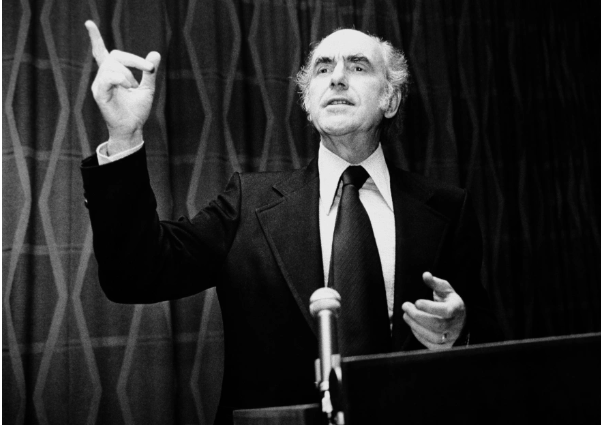

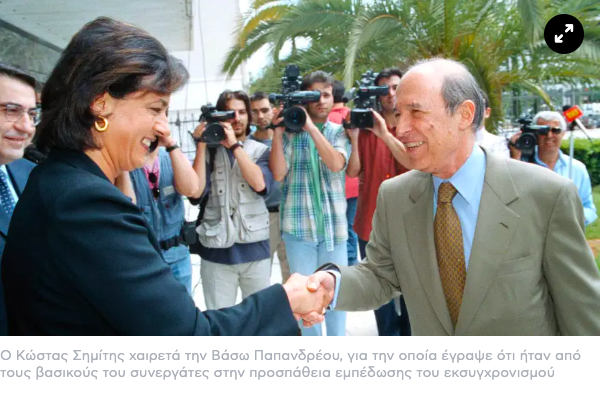

At the heart of it are the personalities. PASOK’s history is inseparable from its leaders. Foremost is the charismatic Andreas Papandreou, who, despite a challenging environment, articulated the demand for a radical transformation of Greek society in the 1980s, encapsulated by the slogan “Change.” In his way, Kostas Simitis also contributed, expressing society’s need for “modernization” in the 1990s, emphasizing Greece’s alignment with Europe, both institutionally and economically.

It wasn’t just the leaders. Alongside them emerged an entire generation of new figures who replaced the so-called “old guard” — the pre-dictatorship politicians burdened with the sins of the post-civil war political system. These new figures, many of whom entered politics through their resistance to the dictatorship, were not career politicians but represented renewal. They became the strength of PASOK, though some later became its Achilles’ heel.

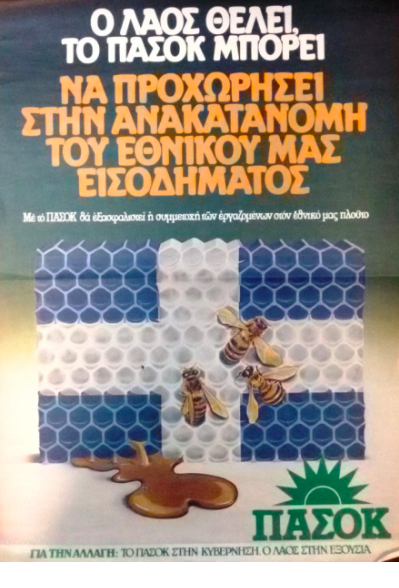

Another key element of PASOK’s strength was its ability to bring together diverse ideological and social groups under one banner. Socialists and traditional centrists, populists and modernizers, Europeanists and Third-Worldists, farmers and the middle class—all united under the concept of the “underprivileged.” Much of this was due to Andreas Papandreou himself and his populist rhetoric, which helped balance a politics of benefits with the economic realities of the time.

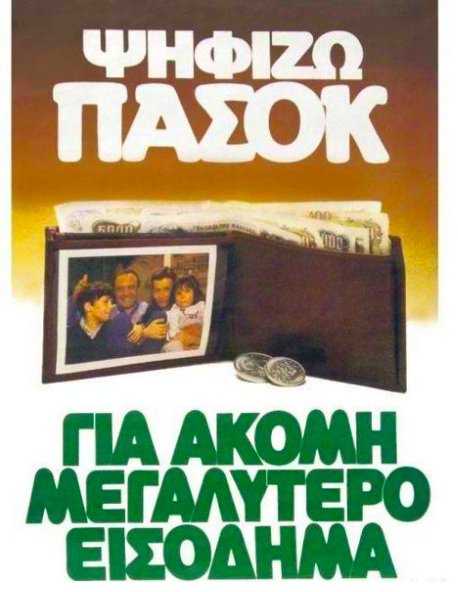

PASOK also stood out for having a clear plan. Unlike today, when governments often seem to follow the media headlines and stumble through problems, most of PASOK’s governments had a clear direction. An exception was the 1987-89 period when PASOK faced turmoil due to the Koskotas scandal and Andreas Papandreou’s illness. In its first term, PASOK enacted major institutional reforms, such as the National Health System (ESY), the reform of family law, the eradication of post-civil war state remnants, and the recognition of the National Resistance. It redistributed income through significant wage increases and introduced Automatic Price Indexing. In education, it implemented the monotonic system and introduced a new law framework for higher education. In the second term, until the 1987 retreat, the focus was on stabilizing the economy. After 1993, the goal was convergence with Europe and joining the euro, accompanied by major infrastructure projects and the 2004 Olympics. It was then that Andreas declared, “Either the nation will eliminate the debt, or the debt will eliminate the nation.”

A final characteristic of PASOK’s governments was their ability to self-correct. PASOK’s history is marked by significant shifts, each of which can be seen as a form of practical self-criticism, albeit not always successful. After the first year, for instance, there was a major reshuffle—a “reconstruction”—with a new economic team and the abandonment of Keynesian economics in favor of demand-stimulation policies. This shift became even more decisive in 1985 under Kostas Simitis as Minister of National Economy, and again in 1993 when Andreas set the goal of economic convergence with Europe.

Similar radical shifts occurred in foreign policy, initially towards Europe through the Integrated Mediterranean Programs, and later towards the United States with the “calm waters” policy, and towards Turkey in 1988 with the Andreas-Ozal meeting in Davos, Switzerland. In terms of state management, PASOK was known for its extensive appointments during the 1980s. However, it was also PASOK, through the Papponis Law of 1994, that established ASEP (Supreme Council for Civil Personnel Selection) and took the crucial step towards regulating these appointments.

Today, PASOK’s legacy is often viewed through the lens of the 2010 financial crisis. As a result, some aspects are criticized with particular severity. The 1980s are considered a lost decade from a development perspective, marked by a dramatic increase in public debt and visible limits of the country’s productive model. Yet, it was also a transitional decade, with the economy tested by competition and many Greek businesses heading toward bankruptcy. These businesses entered the Organization for Problematic Enterprises, burdening the state budget with hundreds of billions of drachmas in a doomed effort to save jobs. It was the beginning of significant deindustrialization. Different management might have led to more rational outcomes but could have intensified social tensions during a period already fraught with unrest following the seven-year dictatorship. This might have been PASOK’s greatest contribution: managing the contradictions of Greek society during a transitional period. It did so with the smallest possible social cost but also with serious economic side effects—costs that, in a sense, we are still paying today.

Nikolas Felekis: Four stories with Andreas

My first meeting with Andreas Papandreou was in 1977. PASOK had become the official opposition and was galloping towards power. I was in the student wing of PASOK and, as I worked at the central offices on Charilaou Trikoupi Street, I was called by someone (I don’t remember who) to inform him about what was happening with PAMK and the students. “What’s your name?” he asked. “Felekis.” “Your first name.” “Nikos.” “Listen, Nikos,” he said, “we will win the next elections. The older folks want to become MPs, and ministers, and take positions in the government. But we need to change the world. I am counting on you and your kids (meaning the PASOK students). You will come once a month to update me on what you’re doing. And make sure the best and most active members join the Youth.” After asking me what we were planning to do next and hearing our ideas, he repeated that the “old folks” wanted positions, but he was relying on the youth, “your kids,” to change the world. When a leader like Andreas tells a young person—truthfully, I did have a bit of a mustache back then—that we need to change the world, you can imagine how I feel. He might have been just flattering me, but at that moment, he made me a… zealot for change. It’s a meeting I’ve never forgotten.

There’s another moment I also remember vividly. It was a Friday afternoon, November 17, 1995, when I dialed the phone number of then-Prime Minister Andreas Papandreou’s residence. I wanted to discuss a serious issue: the forced loan that the Bank of Greece had secured from the Third Reich in March 1942. The newspaper Epitheoristis, which I edited, had exclusively revealed the previous Saturday that the Greek government had requested from a united Germany under Helmut Kohl the return of the occupation loan (38 million gold pounds), which was then estimated at 17 billion dollars or 4 trillion drachmas based on the exchange rate at that time. I remember the details of the call because I had the sad privilege of being the last journalist to speak with Andreas Papandreou before he was admitted to the Onassis Hospital two days later, marking the political and biological end of the late PASOK founder. For details on what was discussed in that conversation, you can refer to the article available online (12/3/2015) titled “What Andreas Papandreou Told Me About the Occupation Loan.”

I will pause here regarding Andreas. Or rather, I should mention another moment with Andreas and the role he assigned to me during the election of Kostis Stefanopoulos as President of the Republic in 1995. For the full details, you can Google “the unknown story of Kostis Stefanopoulos’s election as President of the Republic.” For the historical record, I’ll share that the newspaper Epitheoristis published a front-page headline: “End of the Elections – Stefanopoulos Elected President,” with the subtitle, “On Sunday, Samaras will propose him, and on Wednesday, PASOK’s Central Committee will accept him.” The risk of absolute affirmation was significant. Although the report was certain and from a “first-hand” source, in politics, you never know what might go wrong at the last moment. I took the risk entirely. I wrote about 500 words, and while I usually signed as Aristidis Oikonomou, I signed this piece with my name. If it wasn’t confirmed, I wanted the responsibility for any failure to be entirely mine. The headline made a big impact, especially since almost the entire press particularly the Sunday newspapers suggested that the most likely scenario, due to the inability to elect a President, was that we would face new elections.

Now that I think about it, there’s another story about Andreas worth mentioning. It’s somewhat amusing and perhaps justifies the “thunderbolt reporter” title I was given when covering PASOK as a political editor for Flash 9.61. It was April 2004. Andreas was receiving an invitation to visit the White House for the first time. During his first eight years as Prime Minister (1981-1988), he was somewhat of a persona non grata for the US administration, with Presidents being the hardline Republicans, Ronald Reagan (1980-1988), and George Bush the elder. They considered Andreas almost a communist. In 1992, Bill Clinton was elected President, a fan of Andreas from the time when Papandreou was a professor at Berkeley. In the 1968 uprising, “Papandreou was a legend for us,” Clinton had told us six months earlier during a Europe-America meeting in Brussels.

We arrived in Washington. In Tel Aviv, Olympiakos had just defeated Panathinaikos 77-72 in the Euroleague semifinal. In two days, they would play against the Spanish team Badalona, which had caused an upset by beating Barcelona in the other semifinal. Panos Koliopanos, then editor of Flash 9.61, called me and said, “I don’t know what you’re going to do, Felekis, but Socrates (meaning Kokkalis, who was then the president of Olympiakos and also of the amateur team) wants a statement from Papandreou about winning the cup. They thought it was a sure thing that Olympiakos would win and get their first European basketball cup.” “You’re crazy,” I said. “The first statement Papandreou makes in America will not be about Olympiakos. It’s impossible.” “I don’t care if it’s possible or not. Socrates wants a statement from the Prime Minister about Olympiakos. We’ll have it as our top news when they win the final. Figure it out.” I didn’t cut my throat, so to speak. I called Telemahos Hytiris, the Minister of Press for Andreas. “Forget it,” he told me. “Please, ask him,” I pleaded. “I’ll ask him, Nikos, but I don’t think he’ll agree.” A little later, he called me back, “He almost cursed me out. And rightly so.” “Telemachus, is it possible that my first statement as Prime Minister in America is about Olympiakos?” I said, echoing what I had told Koliopanos.

I tried through Teti Georgantopoulou, a close collaborator of Dimitra Liani. No luck there either. What to do, what to do? The next morning, I decided to go to the Hay Adams, the hotel where Andreas was staying. That day, Papandreou was to visit Congress. I sat in the hotel lobby and waited. After about forty-five minutes, the doors of the two elevators opened. One had Andreas, Dimitra, and his security, and the other had Karolos Papoulias, then Minister of Foreign Affairs, Telemahos, Teti, and others from the delegation. As they exited the elevator, I rushed up and stood in front of Andreas. Everyone was surprised. “Mr. President, I have good news,” I said. “What, Nikos?” he asked, puzzled. “Olympiacos has won the European basketball championship, and I would like a statement,” I said boldly, pulling out a small tape recorder from my pocket. No matter how many years pass, I still remember his statement: “What can one say but to rejoice in the great successes of Greek sports? Congratulations to Olympiacos for winning the European basketball championship.” “Thank you very much, Mr. President,” I said and stepped aside for him to pass. As you can imagine, the expletives I received, as Hytiris later relayed to me, were indescribable.

Anyway, I had done the job. Socrates wanted a statement from Andreas, and he got one. The game, of course, had not yet been played. I sent the statement, but for it to make news, Olympiakos needed to win the final. Olympiakos didn’t win. They lost by two points. Zarko Paspalj had missed key shots in the last five minutes. So, I had the statement left over. In 1996, Andreas passed away. In 1997, Olympiakos won their first Euroleague cup in Rome. I still have the tape of Andreas’s statement congratulating Olympiakos. The dilemma was significant: should I release the statement to the radio and cause a stir? Just think about it—Andreas’s statement from the beyond for Olympiakos. I decided to later write the story in Symbol, the magazine of Epitheoristis. Petros Kostopoulos read it and called me. “Man, I’m dying of laughter. Please give me the statement so I can play it.” I don’t remember which radio or TV station he was on. I still have the statement. If Olympiakos wins the Euroleague this year, I’ll look for it in the basement of my house, buried among many other mementos, and I’ll have it broadcast.

When asked to write something for PASOK’s 50th anniversary, I thought about how everyone is writing analyses about what PASOK was, what it is, and whether it can become a major governing party again. At some point, I’ll write too. And I have, truthfully, a lot to say. Experiences. Memories. Any suggestions? Today, I chose to write, in memory of Andreas, and because “we need to change the world,” four small and largely unknown stories…

Dimitris Pagadakis: “Andreas, what are you trying to do?”

At 9:05 PM on the warm Friday evening of August 16, 1974, the Olympic Airways plane, City of Mycenae, touches down at the Ellinikon Airport. On board is 55-year-old Andreas Papandreou, returning to Greece from Toronto, Canada, via London. It’s his first return to Athens after seven years of enforced exile. By July 24, 1974, the junta of colonels had collapsed under the weight of its crimes, culminating in the national tragedy in Cyprus.

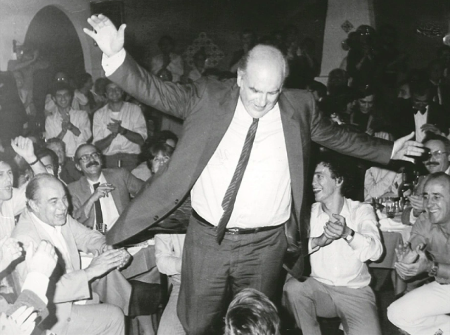

At the airport, he is met with an overwhelming reception. A massive crowd greets him with deafening cheers and thunderous slogans. Thousands rush to touch him, embrace him, and carry him triumphantly on their shoulders. The sea of people accompanies him in a celebratory procession to his family home in Kastelli.

Having survived the oppressive outpouring of adoration, the man who escaped annihilation at the hands of the brutal junta is now assured of surviving any attempt against him. He would even withstand an excessive dose of Carmina Burana. His shield is the mass appeal and the warm embrace of the people.

He returns with his luggage filled with dreams, hopes, plans, and visions. He intends to play an active role in shaping the post-junta political landscape. He aims to transform the modern Greek political body, sweep away the old political contracts of power, and thoroughly dismantle the entrenched traditional seats of wealth and influence.

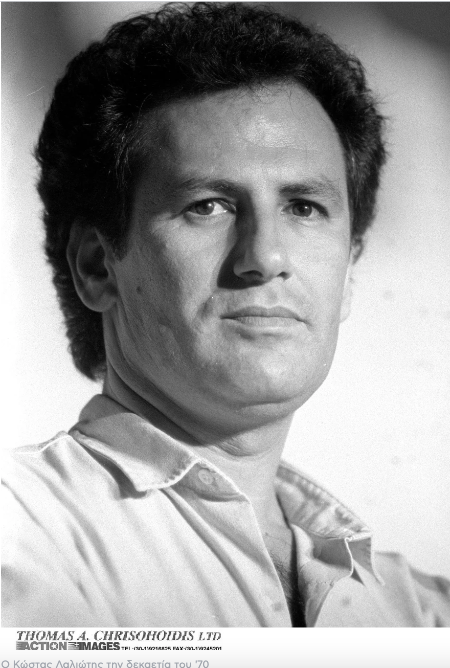

The “new” Andreas is strikingly different from his recent past. Wearing a leather jacket, an open-collared shirt without a tie, a wide perforated wristband instead of a watch strap, a broad belt with a large buckle, and sporting long sideburns, he tests out turtlenecks. This is a far cry from the stereotypical public image of the former minister in his father’s pre-junta governments.

The serious and critical Keynesian economics professor from American universities has changed course. He has adopted a radical ideological identity and an innovative political role. He is now counted among the internationally influential neo-Marxist, anti-imperialist figures. He fits into the mold of the nationalist liberation leaders of the late 60s and early 70s.

He speaks “loud and clear” about the “corruption of the national economy by Western multinational corporations, with the ongoing collaboration of local merchant capital.” He seeks to break with the past, looking for ways to disengage from the old political system of foreign dependence and the interventions that led to the dictatorship. His goal is to rid the country of the control and influence of the economic oligarchy.

The deeply conservative right, hearing his tempestuous rhetoric with its condemnations of the US, NATO, the CIA, and monopolies, is infuriated. They envision him as a battle-hardened commander in tropical South American jungles, armed with bandoliers and wearing a Che Guevara beret. In reality, he has long recognized that the politician with the stirring rhetoric will soon become their major adversary.

His sharp, combative discourse surpasses even the aggressive agitation of the “Voice of Truth,” the radio station of the illegal Communist Party of Greece (KKE) broadcasting from Bucharest until September 1974. However, his eloquent voice stirs a segment of the left, inspiring and motivating those worn down by the post-civil war state, the former EAM fighters of the National Resistance.

On the other hand, respectable democrats, sober anti-monarchists, mild liberals, traditional Venizelists, and centrist bourgeois are on the verge of a mental breakdown with his blunt and straightforward statements. The courteous Andreas listens attentively to their objections but does not share their concerns. He has no intention of following his old comrades into a political quagmire.

As a perceptive intellectual, he understands that the moribund local political system, with its tattered ideological armor and perforated institutional framework, no longer responds to the conditions of leftist political radicalism ignited by the dictatorship and further fueled by its collapse.

His thoughts align precisely with the historical moment. He recognizes the particularities of domestic social stratification and is inevitably driven to represent and politically express the social alliances that will emerge with a new collective entity. Under his voluntarism, the political horizon is open here and now.

He is poised to initiate his project by founding a new party. Not just an organizational mechanism, but an ideological educator and strategic organizer of the field, merging “material forces and ideology.” All this in less than 20 days.

Of course, no party emerges out of nothing or from virgin birth. Andreas consistently follows the evolution of the Panhellenic Liberation Movement (PAL), the resistance organization he founded during the dictatorship in Stockholm in 1968. Before coming to Greece, on August 6, 1974, he convened the final national council of PAL in Winterthur, Switzerland.

There, about 80 of his comrades decide to dissolve the organization and abandon the armed anti-dictatorial struggle following the junta’s fall. At the meeting, however, the demand for the creation of a new political entity remains irresistibly alive. A new entity capable of effecting radical changes “with the ultimate goal of the socialist transformation of Greek society.” This is the aim of the founder of the organization is to give creative form to in his homeland.

A few days after he arrives in Greece, Andreas performs a memorial service at the grave of Georgios Papandreou at the First Cemetery. The junta had forbidden him from attending his father’s funeral on November 1, 1968. At the ceremony, all former MPs of the Center Union and a large crowd are present. The chant resonating through the cemetery is: “After the Old Man, Andreas.”

Although he has severed his ties with the traditional pre-junta Center, prominent political figures from that era, who have never admitted his departure from what they consider his political roots, insist he leads the party. They want it to continue with a renewed identity, continuing the legacy of the “Patriarch of Democracy.”

“Andreas, what is he trying to do?” they plead. “We have a ready-made party here, all set. Is he really going to start experiments now?” Their pleas go unheard. Andreas Papandreou has taken a bold political gamble and boldly crossed the Rubicon of the outdated party landscape.

He does not feel burdened by his family name. Nor does he wish to be merely his father’s political successor. Instead, he leaves behind a promising yet stifling legacy and seeks out fresh, green pastures. A politician with a well-defined vision does not merely talk about his dreams; he realizes them in full.

In essence, he acts according to his political conscience with the confidence that he is undertaking a historic initiative. He set the date for the commencement of this initiative on September 3, 1974, a date permanently etched in Greek history.

On that Tuesday, he publicly unveiled the declaration conceived in Winterthur, written in Munich, edited and finalized in utmost secrecy in Kifisia. Standing in the King Palace Hotel, on the corner of Panepistimiou and Kriezoti streets, Andreas Papandreou reads the declaration in full to an audience of 150. These include members of the PAK from both abroad and within Greece, anti-dictatorship fighters persecuted by the junta, Polytechnic students, and adults from the democratic generation of 1-1-4.

These individuals formed the core of the new party named the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK). This movement is characterized by its principles condensed into the quad: “National Independence – Popular Sovereignty – Social Liberation – Democratic Process.” The rest is history, spanning half a century of domestic political evolution.

Dimitris Danikas: Are we all PASOK?

Fifty years since the founding declaration of September 3rd by the late Andreas Papandreou, the remaining supporters sing praises. The “rootless” nostalgically reminisce. Opponents replicate and adapt. Some of Andreas’ “children” and grandchildren seek leadership.

Future historians will record, assess, and calmly evaluate this legacy. For now, and admittedly in a preliminary manner, it is possible to categorize PASOK into two categories: the positives and the negatives, without convenient compromises.

Andreas indeed initiated significant reforms. These were indeed groundbreaking for Greece but not necessarily for Europe. Such reforms include the decriminalization of adultery, and divorce, gender equality, the National Health System, the destruction of files on political beliefs, democratization in all sectors, and the creation of ASEP (Supreme Council for Civil Personnel Selection).

Simply put, Greece in the 1970s was struggling to catch up, albeit distantly, with the pace of its European allies. It was like taking one step forward and two steps back, as the late Lenin said.

Simultaneously, the slogan “EC and NATO are the same syndicates” magically transformed into “with both the EC and NATO.” Nearly all Greeks over fifty managed to secure pensions for resistance actions they might not have performed. In other words, a plethora of consciences, particularly supporters of EDA, were bought off.

The “rightful children” secured public sector positions, with their salaries paid by the private sector. Many of these “children,” from semi-literate backgrounds, turned public services into a torment for citizens.

The tsunami of appointments was justified by the argument “We will hire as many as needed to balance the record of hiring by the ‘right-wing children.'” One side sewed, the other unraveled. This reflected an ideological obsession equating every government with the state: “What’s mine is mine, and what’s yours is mine.”

With Mediterranean programs, farmers engaged in consumerism, buying expensive private vehicles and more. During the PASOK era, nearly every farmer and shepherd reported double the number of olive trees and sheep compared to Italians and Spaniards. The iconic epitome of this was the famous slogan “Tsohvola, give it all.”

Thus began the first act of the play “The Unleashing.” The second and final act, with Kostas Karamanlis Jr. as Prime Minister, who was also enchanted by PASOK’s green, saw Greece transition from this excess to become Europe’s junk food, with debt exceeding three hundred billion.

They consumed endlessly without considering their children and grandchildren. They devoured even the bones of borrowed and irretrievable money. Thus, the innocent and somewhat reckless George Papandreou inherited the expensive “trash.” He requested, without consent, cooperation with Antonis Samaras’ New Democracy. And so, Samaras, with his Zappeio plan and the tearing up of memorandums, launched and propelled Alexis Tsipras to the governorship. And thus, for a decade, Greeks have been paying the price of this excess. But the party is over.

Yet, despite everything, the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) continues to move forward, somewhat surreptitiously and with a certain grandeur. Many of Kyriakos Mitsotakis’s successful ministers come from PASOK. Kyriakos himself has roots in Venizelism, just like Andreas Papandreou. Alexis Tsipras once paraded himself as a caricature of Andreas Papandreou. Even Stefanos Kasselakis, the “tourist,” shares that same legacy. Numerous green cadres have shifted, whether from here or there.

Thus, the Center in Greece remains vibrant and somewhat PASOK-like, whether leaning left or right, in the style of Simitis. Today’s aspirants to the party look up to Andreas as their god, regardless of the missteps and actions of some who claim his mantle.

The crucial question remains: with which PASOK does one stand? The one of excess or the reformist one? This needs to be clarified. Society must mature. The cicada must become an ant, and the modern Greek must become productive.

And a wish to those who will rush to vote for a new leader: may it be for the best. However, beware, robes do not make the priest!

Stefanos Tzanakis: If Andreas were alive today…

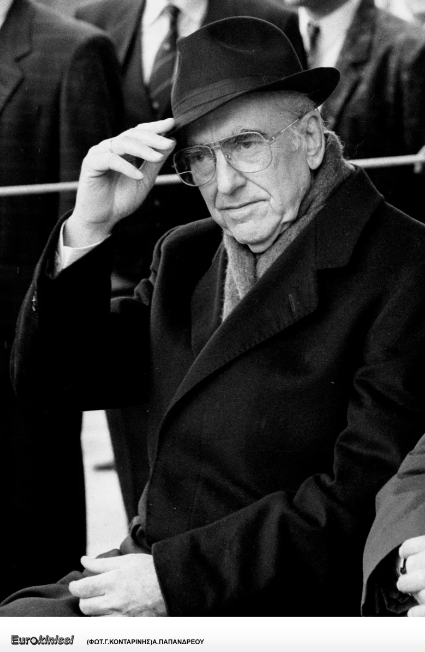

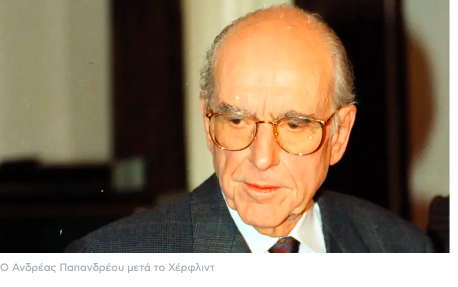

Andreas Papandreou founded PASOK in 1974, shortly after the fall of the junta, and led it until late 1995—formally, until mid-January 1996, when he resigned for health reasons following his ordeal at the Onassis Foundation. Twenty-two years were enough for him to leave a lasting mark on Greek history.

The rise was explosive until October 1981 when PASOK won the elections and formed a government: From 13% in ’74, it rose to 25% in ’77 and reached 48% in the change elections—a percentage that fell short of the expectations cultivated, as on the night of those elections, not only PASOK voters celebrated but also the KKE and KKE (Interior) supporters.

In its early years, PASOK was little more than a leftist party, though it managed to include members from the pre-junta Center Union. Andreas’s influences were American New Left and various Third World Movements—from the Tupamaros and Viet Cong to the PLO and Ba’ath. And of course, the portrait of Aris Velouchiotis dominated the offices on Charilaou Trikoupi.

After the 1977 elections, Papandreou began making room for centrists, swapped his turtleneck for a shirt and tie, and started advocating for a special relationship with the then EEC, which he had previously denounced. And when the time came to govern, he comfortably negotiated with leaders he had once condemned. By the end of the beginning—after 1981—PASOK was an expanded Center Union, with Menios Koutsogiogas and Antonis Livanis gaining increasing power.

For many years, PASOK was nothing more than “Andreas’s party”—but everything seemed to change in 1989, when PASOK lost to New Democracy under Mitsotakis, despite a slight drop from 40%. Papandreou faced an open challenge for the first time at the Penteli Congress—when Giorgos Gennimatas rushed to support the election of Tsohatzopoulos and avert the worst. However, it was clear that the less-known PASOK members were looking for ways to emancipate themselves from the founder.

What politically saved Andreas and gave him the chance to return to power in 1993 was what the KKE considered the “nuclear weapon” that would bring PASOK votes to the KKE—namely, his referral to the Special Court due to the Koskotas scandal.

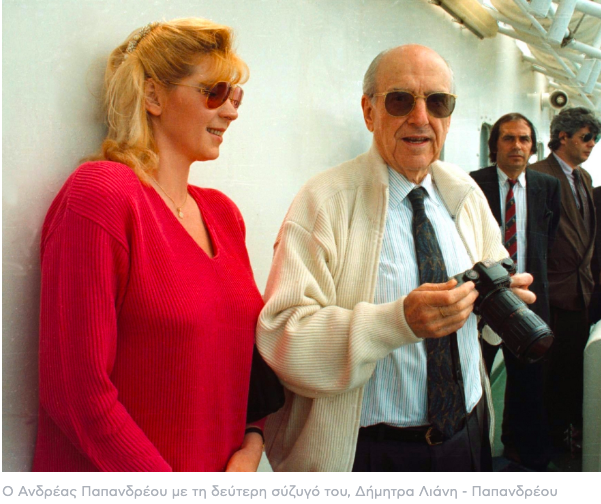

The two years he governed in the 1990s had a dual flavor: on the one hand, the photos with his second wife’s entourage created a farcical atmosphere, and on the other, the economic policies he followed, which gave Greece the chance to approach Europe and begin its path toward eurozone membership.

His successor, Kostas Simitis, continued Papandreou’s policies with even greater intensity, securing Greece’s entry into the euro and aligning the country’s trajectory with the European average. However, PASOK was no longer the same: it was never to become “Simitis’s party”—this was clear—but it was no longer just one party but two.

While Akis Tsohatzopoulos accepted his defeat at the 1996 congress, the cadres (and voters) who had been convinced by Andreas that PASOK was the party of the “disenfranchised” did not feel the same about Kostas Simitis. Although power masked the internal party divide, when the time came—with the Memoranda—voters and cadres from Tsohatzopoulos’s side migrated en masse to SYRIZA, even considering Alexis Tsipras as the “new Andreas” for a significant period.

Simitis received 44% in the 2000 elections and secured a second term, but just before the end of his term, it was clear he would not win the next election, even though the country was growing rapidly and income convergence with the rest of Europe was continuing.

Thus, PASOK returned to Papandreou—the younger—whose time had come at the most challenging moment for the country: the crisis that had begun in the U.S. in 2007 was approaching Greece, but Simitis was no longer in government—he could only warn, which he did in vain—while the “modernizers” had been expelled from PASOK’s leadership.

Georgios Papandreou’s 44% plummeted to 4.7% for Evangelos Venizelos in the first elections of 2015. PASOK voters waved goodbye to their party and felt at home in the “anti-memorandum” camp of Alexis Tsipras and Panos Kammenos.

When SYRIZA’s downfall came, former PASOK voters kept Tsipras’s party at 32% and kept PASOK under Fofi Gennimata in single-digit percentages, as many centrist voters chose Kyriakos Mitsotakis’s New Democracy “to remove Tsipras.”

Today, PASOK stands on the brink of electing new leadership. No one can predict the outcome at the polls—what is certain is that interest in the party is at its peak from both the right and the left. The prolonged crisis within SYRIZA and the anticipated, yet real, erosion of New Democracy have been crucial and necessary factors in this surge of attention. However, two questions remain: beyond “who” will be elected, there is also the question of “how” the winner will govern. If Andreas Papandreou were alive, we would already have answers to both questions. For now, we must wait and see what life has in store.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions