The issue of water-logging that experts say our country is facing due to prolonged drought has led the relevant agencies to mobilize. The problem of water scarcity is of course a headache for EYDAP which has to take care of the water supply of a large part of the basin and especially the capital and the surrounding municipalities.

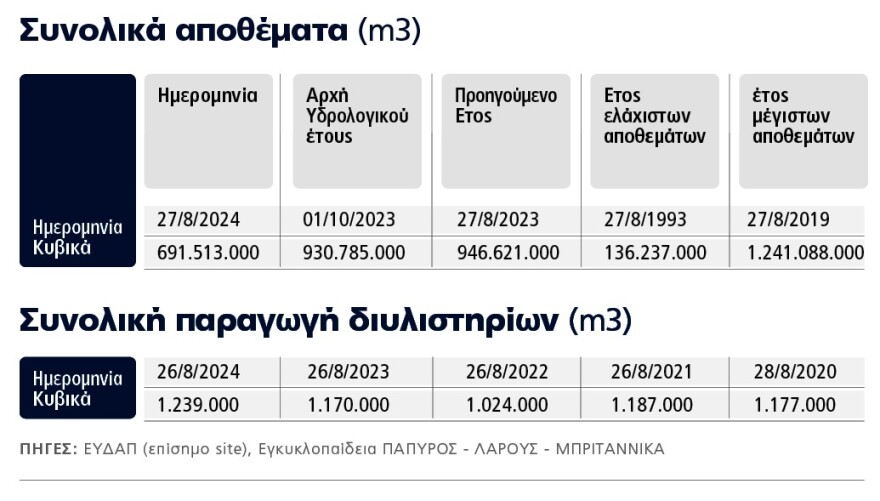

Lately we have been hearing all sorts of things about the risk of water shortage in Athens, emergency measures, etc. If we look at the Reserves Bulletin issued daily by EYDAP, the water reserves in its reservoirs are around 690 million cubic meters of water. Five times (and more) than in the year of minimum reserves (1993), but about 2/3 of the reserves of the corresponding date last year and almost half of the reserves of the year of maximum reserves (2019).

Of course, the situation is neither marginal nor critical, but caution is needed. If the prolonged drought continues, there will indeed be a serious problem. The hydrological year begins on October 1. If the coming autumn and the following winter are not accompanied by rain and snowfall (especially these are precious), especially in the areas of Mornos, Eynos and Yliki, the summer of 2025 will be very difficult. Finally, we should note that not all the water in the reservoirs is withdrawable (pumpable) as there is a certain safety limit.

The Adrianio Aqueduct

But the problem with Athens’ water supply is not a current one. It begins in antiquity. We will see how it was dealt with for hundreds of years with the Adrianeion Aqueduct, remnants of which still exist in Attica today, and how in later years, with the rapid growth of the capital’s population, solutions were sought for new sources of water supply. It impresses with an 1899 report that could have been written today. One of its authors was Petros Protopapadakis, later prime minister and one of the “six” executed in 1922 in Goudi. We will also deal with the issue of the capital’s drainage from antiquity to the present day.

The problem of water supply has existed in Athens since ancient times. The inhabitants of ancient Athens used the waters from the springs of Parnitha, Penteli and Ymittos, as well as the city’s rivers, Kifissos, Ilisos and Iridanos. The first aqueduct was the Peisistrateion (530 BC). The Philhellene Roman Emperor Hadrian (117-138) took up the subject, constructing the Hadrianic Aqueduct, among other projects in Athens.

Work on its construction began in 134 and was completed in 140 by Hadrian’s successor, Pius Antoninus. The Adrianeio Aqueduct carried water from Penteli and Parnitha through tunnels to the area of Lycabettus, where it was stored in a stone-built reservoir with a capacity of about 500 cubic metres. Its total length was 20-35 km. For about 1,800 years there was no additional water supply project in Athens! In fact, in the years of the infamous Haji Ali Haseki, the Ottoman governor of Athens in the last years of the 18th century, the aqueduct was destroyed.

When the new Greek state was founded, the Municipality of Athens sought the tunnels of the Hadrianic Aqueduct. Indeed, in 1840, engineers of the municipality managed to locate them. The cleaning of the tunnels was then begun, with the simultaneous reconstruction of most of the shafts. The work continued for many years and largely restored the aqueduct’s operation. In 1870 the cistern at Kolonaki was discovered, which had fallen into disuse as it was first converted into a stable, then a church and finally filled in. The reservoir was cleaned, expanded and reached a capacity of 2,200 cubic metres of water.

During the years of Charilaos Trikoupis and in 1899 under the government of Con. Theotokis, the issue of water supply in Athens was again discussed, but financial reasons did not allow anything to be done. The same happened in 1911, when Eleftherios Venizelos was prime minister. However, the Balkan Wars (1912-1913) and the First World War cancelled any attempt to do so.

ULEN and Lake Marathon

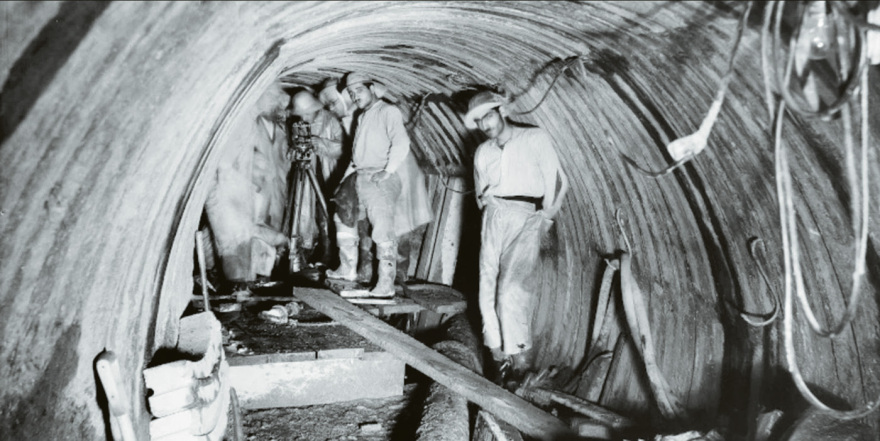

After the Asia Minor Catastrophe and the rapid growth of the population of Athens, it was more than necessary to find a permanent solution for the water supply of Athens and the surrounding settlements. After many disagreements, the solution came on 23/12/1924 with the signing of the contract between the Greek State, the American company ULEN and the Bank of Athens. In 1925 the first modern water supply projects in Athens began. According to the contract, ULEN undertook the construction, maintenance and operation of the water supply projects of Athens, Piraeus and the surrounding area. The Athens – Piraeus and Periphery Water Company (AEEY) was also established.

From 1926 to 1929, the Marathon Dam was constructed, which is lined with Pentelic marble, 54 m high and 265 m long. Its interior is made of concrete, made with crushed marble, cement and volcanic ash. The construction of the dam created the artificial lake of Marathon at the confluence of the Haradros and Varnavas torrents, with a total capacity of 44 million cubic meters of water.

To transport water from the Lake Marathon to Athens, the 13.4-kilometre-long Bogiatiou (Agios Stefanos) tunnel was constructed. This tunnel carries raw water to the water treatment plant in Galati and from there it is piped through a new network. In June 1931 the new water supply system of the capital was inaugurated.

Until 1940, the Adrianio Aqueduct operated in parallel. After the end of World War II and the Civil War, the population of Athens increased significantly. After further disagreements, it was decided to use the waters of Lake Yliki in Boeotia. As the lake is located at a low altitude, the water is pumped by a series of pumping stations. The main pumping station of Yliki is the largest in Europe. Again, however, the water supply needs of Athens and the surrounding municipalities were increasing.

The Mornos Dam

In 1965 it was decided to carry out a study to transfer water from the Mornos River (in ancient times it was called Dafnos) in Central Central Sterea. The junta awarded the project to a consortium company using the self-financing method. The design for the project was delivered in 1968. It was put out to tender in 1972. In 1978 the contract was revised. By 1979 the project had cost 16 billion drachmas against an original budget of 4.7 billion! It was inaugurated in November 1979 without being completed! It operated on a trial basis in the summer of 1980, but only for a short time. Damage soon occurred, and the earthquakes of February 1981 caused further damage. (Information about the adventures of the Mornos dam is not available on the official site of the EIDAP and comes from the encyclopedia Papyrus – Larousse – Britannica)

Finally, finally in 1981 Mornos started to supply Athens with its waters. Its earthen dam (126 m high) is the highest in Europe. The prolonged drought resulted in the early 1990s in the reserves of the EYDAP reservoirs reaching marginal levels. The solution was to divert the river Euinos (Feidari) of Western Central Greece to the Mornos reservoir by constructing a 29,4 km long tunnel. Two large reservoirs, the Mornos and the Yliki reservoirs, were constructed for the transport of raw water, and unified aqueducts were built to transport the water to the four water treatment plants of Galatsi, Polydendriou, Aspropyrgos and Acharnon.

The 1899 topical study

On March 25, 1899 Andreas Cordellas, an engineering metallurgist, Elias I. Angelopoulos, a legal engineer, and the engineering metallurgist Petros E. Protopapadakis presented a study-proposal for “the definitive solution” to Athens’ water supply problem. The three scientists proposed the transfer of water from Lake Stymphalia in Corinthia and the Kifissos River in Boeotia. They estimate that the works required would cost 40 million drachmas. We were particularly struck by one paragraph of the study. In it, Cordellas – Angelopoulos and Protopapadakis reproach those who believe that Attica can supply its own water to the growing population of Athens and Piraeus:

“To those who claim that the Attica basin and the surrounding mountains can provide abundant and good quality water in a quantity sufficient for the day by day growing population of the two cities (Athens and Piraeus) we reply that not only is this not certain, but even if it were, the drainage of the soil would be such as to completely change the appearance of the Attic basin, depriving the waters of all private estates in general and transforming it (the Attic field) into a ‘complete Saharan’.” (We have rendered the text in demotic, as it was written in clear Greek)

The drainage project

An equally big issue for Athens and Attica in general is that of sewerage. In ancient times the city did not have an organised sewerage network. There were open sewerage systems that created disease hotspots in stagnant places resulting in serious diseases such as cholera and plague. This practice continued for about 15 centuries, when it was replaced by the system of draining sewage into septic tanks. When these filled up, others were opened or the sewage was collected in containers and dumped into streams and rivers, causing huge public health and environmental problems.

In later Athens, in 1840, an attempt to systematically construct a network for the collection and transport of sewage and rainwater began. In 1860, the Stadius pan-torrential drain was constructed by the French. However, according to the encyclopedia Papyrus – Larousse – Britannica, the water of the pipeline (the year of its construction is 1858) ended up in the Kifissos and from there in the sea.

Along the route, the waters were used for irrigation of vegetable gardens (!), with the result that epidemics often broke out. Between 1880-1890 the open stream of Kyclovoros was covered with a large diameter (about 3 meters) stone-built drain. By 1893, 11,5 km of sewerage network had been constructed, but the need was for a network of about 90 km. In 1922-23, after the Asia Minor Catastrophe and the rapid increase in the population of Athens, new discussions and studies for the city’s sewerage system began. By 1925 the Municipality of Athens had constructed two large sewers on Marni and Paioniou Streets, and began covering other streams.

However, a serious epidemic of dengue (1928) and a flood in 1929 brought the issue of sewerage back to the forefront. In 1930 the construction of a sewage pipeline of the Prophet Daniel stream was completed with the final destination being the Faliric Delta. It was a pipeline with a length of 6.5 km on land and 700 m underwater. In 1933, the State commissioned a study to a consortium of contracting companies, which formed the Athens and Periphery Sewer Construction Company (later Ydrex) for the construction of sewers for sewage and rainwater based on the preliminary study by Professor Fandoli.

By 1931-32, private individuals had been prohibited from constructing absorption cesspools on streets with sewer systems, while the municipality removed the right of private individuals to construct any kind of sewers.

From 1934 to 1939, important works were carried out: 17 streams were covered, the large sewers of Rigillis and Vasilissis Sophia and the flood control ditch of Filopappou Hill were constructed. On the basis of the Fantoni preliminary study, three important projects were carried out despite the Second World War: the construction of a central sewer, the construction of a large and basic collector for the Kifissos and the settlement of parts of the Ilisos.

The dormitories of the ’70s and ’80s

The new large increase in the population of Athens after World War II led to the operation of the OAP in 1954. As early as 1950, a preliminary study had begun to drain the capital city over an area of 200,000 acres. The preliminary design was delivered… The preliminary plan was delivered in 1963 (of course we are ironic about the delay in its preparation), but with various modifications, but it formed the basis for the construction of the Athens sewerage system. From 1950 to 1980, 1,700 km of sewage pipes and 300 km of storm water pipes were constructed, the Parakifisio Collector and the Paraliaikos Collector of the Saronic coast.

A study by the English company Watson in 1976 was considered unacceptable by the Technical Inspectorate. The study in 1977 proposed that no sewage sewers should be built in Thriasio, West Athens, Mesogeia and the coastal areas of South Evia and Saronic Gulf, but only septic – absorbent cesspools and 21 regional cesspools.

In the meantime, the tankers for emptying cesspools were emptying in the cesspool of Schistos, which due to repeated failures was rendered useless. In 1978 the government of Con. Karamanlis proposed the creation of 8 regional cavuzas (in Argyroupoli, Metamorfosi, Kalogreza, Petroupoli, etc.) and stirred up a storm of reactions from the residents of these areas, but also from Keratsini, who demanded the removal of the cavuzas from their area. Keratsini and Amfiali suffered most from the stench of the cavius, which was a health bomb for the whole of West Attica. The protests and fierce clashes with the police culminated in 1980, when the government attempted to open ditches in the southern part of Maroussi and repair the Keratsini havouza.

In the same year, the Greek Water Company (Hellenic Water Company) of Athens, Piraeus and Surroundings and the OAP were merged. This led to the creation of EYDAP (the Capital Water Supply and Sewerage Company), which took over the obligations of the former OAP, except for the construction of secondary sewage pipelines and the connection of properties to the networks assigned to the local authorities. In recent years the Athens sewerage network has been extended and its total length has reached 8 000 km.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions