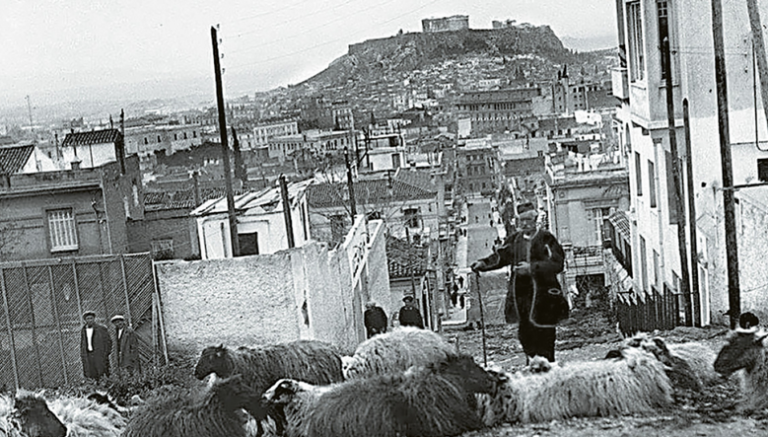

Walking through the bustling streets of central Athens, whether as a resident or a visitor, or taking in the view of the sprawling, densely built capital from a balcony on one of its nearby hills, it’s nearly impossible to grasp that less than two centuries ago, this city was merely a tiny dot on the map. It was a vast field with orchards and pastures, bisected by two rivers that were fed by dozens of streams and torrents flowing from the surrounding hills and mountains that define the basin. Greenery was abundant, vegetation thrived, and the few inhabitants lived mainly off agriculture and livestock farming. They grazed sheep and goats, cultivated the land, and kept vegetable gardens and chicken coops. Out of this pastoral landscape, modern Athens was born—through many struggles, sweat, and hard work.

It’s no exaggeration. Today’s Athens, with its official population of 3.5 million in the metropolitan area and 626,000 in the city proper, is largely a product of the past few decades, a sharp contrast to its over two-thousand-year-long illustrious history as the cradle of democracy, culture, and the core principles and values of humanity. This transformation followed the decline it faced after antiquity, through the Byzantine and Ottoman periods, which left it dormant.

This is why, unlike other European metropolises that grew and expanded at a more natural pace, Athens, upon becoming the capital, was pressured to respond to the overwhelming needs of each era: after the Ottoman period, the Asia Minor Catastrophe, and World War II. It was forced to accumulate much: people, households, hopes and visions, labor, suffering, and creation, thereby revealing new colors as it shaped its new identity while also spending some elements of its heritage.

Nevertheless, it remains one of the most sung cities in the world, with 239 titles on album covers, according to official data. “The Joy of the Earth and the Dawn, little blue lily” by Manos Hadjidakis, Nikos Gatsos, and Nana Mouskouri, although none of them were born there, loved and celebrated the city. It is one of the “official favorites” for global citizens. The images from the past through the rare diamond photographs of 19th-century Athens bring to life memories that the younger generations “long for endlessly, even though they have never lived them,” as Tasos Livaditis, a native of the city, describes. When Athens was proclaimed the capital of the new Greek state on September 18, 1834, by decree of the regency of Otto, it had fewer than 5,000 inhabitants. At the same time, the truly large city of Thessaloniki, still under Ottoman rule, had around 60,000 residents, while Tripoli and Patras had about 15,000 each. In Europe, Paris and London had close to one million inhabitants, with 300,000 and 500,000 respectively in 1650. Berlin reached similar numbers by 1875.

By 1848, the official census reported a population of 26,256 in Athens, and by 1861, 43,374. Gradually transforming from a small town into a city and metropolis, its population steadily increased, with demands far exceeding the infrastructure available. In economic terms, today Athens contributes 20% of Greece’s GDP, approximately 48 billion euros, while Attica accounts for 50%, or about 120 billion euros. In the mid-19th century, the economic output of Athens was merely a pittance.

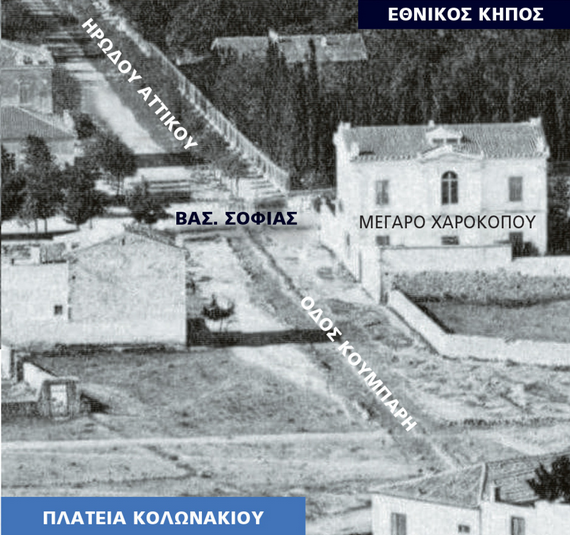

Modern Athens began to develop first around the Acropolis, in Plaka. Gradually, the focus of its new chapter shifted to the neighborhood bordering the centers of state power, Kolonaki. A historical photograph from 1874 showing Kolonaki from Lycabettus is striking. This area, which would later become a laboratory of political action, a hub of cultural creation, and a catalyst for social mobility—a favored meeting point for artists and intellectuals, sometimes a space for fulfilling urban dreams and a grand life—was once a simple pasture with fields and very few houses. In the same photograph, the Royal Garden, Vasilissis Sofias Street, and Irodou Attikou are visible. In the center is where Kolonaki Square would later be established—the most expensive area in today’s capital, not only in terms of real estate values and wealth but also in terms of spiritual and political power.

Kolonaki owes its name to an ancient pillar located approximately in the center of the square of the same name. Originally, it was situated in the Dexameni, next to the Hadrianic Aqueduct, and the ancients attributed healing properties to it, believing it could prevent diseases, epidemics, and natural disasters. Sick individuals would hang and tie their clothes with ribbons on it to seek healing. The pillar was permanently moved to the square in 1938. This central square, which today is hidden behind the construction barriers of Metro Line 4, was shaped in 1870. It was initially named Queen Olga’s Square. Later, it was renamed Kolonaki Square, although its official name is Philiki Etairia Square.

A Distinct Area

No other area of Athens has evoked as many conflicting and intense emotions as Kolonaki. It has sparked extensive discussions, a strong desire, as well as skepticism, a great deal of love and passion, but also antipathy, envy, and creation. It has been a source of explanations and misunderstandings, serving as a platform for political actors, thinkers, scholars, writers, and artists. During the Ottoman period, the area was uninhabited. It was known as Katsikada or Katsikadika, as it was the city’s vast pasture, full of stalls for shepherds on the welcoming slopes of Lycabettus. In Otto’s time, it was a countryside with vineyards and fields. Up until 1880, it remained sparsely populated. Above Dexameni, predominantly inhabitants from Sterea Hellas, from places like Lidoriki, Mousounitsa, and other villages, continued to graze their goats and produce milk.

The sight of a dairy farmer milking his goat in the middle of the street was commonplace and did not surprise anyone. Throughout Kolonaki, even at its boundaries with University Street, which was still a dirt road back then. In the background of this milking scene were the splendid neoclassical buildings of the Academy of Athens, the University, and the Library. In what would later become Athens’ most aristocratic neighborhood, the smell of goat milk and manure permeated the air. It is thus very difficult to imagine, or to only feel some flavors from the few photographs of immense cultural and social value that exist, that in Kolonaki, where today the streets are intimidating with their real estate values, the stores filled with dozens of top-tier brands, corporate offices, and residences, there were once streams and brooks. Like the stream of Vukurestiou, which was originally named after the ancient name of one of the peaks of Lycabettus, as well as the other rushing stream that also descended from Lycabettus, branching into two, following the present-day streets of Dimokritou and Lycabettus, until it ended in the gorge, the Voïdopnithis, near Academy Street!

The doctor and chronicler of the time, a close collaborator of Ioannis Kapodistrias, Andreas Papadopoulos-Vretos, described: “In the year 1834, Athens was declared the capital of the new kingdom, but this remarkable city was then a miserable small town […] barely four thousand residents crowded into huts. (The city) was crossed by narrow and filthy streets, marshes exuding poisonous vapors everywhere, and only a few dry trees could be seen.”

Even today’s Stadiou Street remained a deep gorge that descended from Lycabettus until 1845, passing through today’s Korai Street and ending at Kotzias Square, in front of the town hall. It was a paradise gorge for hunters, as it was filled with vegetation, dense reeds, bushes, and trees where hares, rabbits, partridges, pigeons, and other small animals nested.

The Dexameni

A significant landmark both then and now is Dexameni. Since the time of the Roman Emperor Hadrian, in 134 BC, it continuously supplied Athens with water until just a few years ago. The water came to Athens from springs in Acharnes and was stored in a reservoir at the foot of Lycabettus, at an elevation of 136 meters.

In the early 20th century, giants of Greek intellect such as Georgios Souris, Alexandros Papadiamantis, Kostas Varnalis, Ioannis Kondylakis, and Nikos Kazantzakis, later joined by Odysseas Elytis, frequented Dexameni. Kostas Varnalis wrote in his memoirs about Dexameni: “There I found, along with the tall trees, the clean air, the sun, and the distant view of the Saronic Gulf, which intoxicated me with its tranquility and brilliance, the best version of myself.”

From Poor Neighborhood to Luxurious Mansions

However, for many years—from the interwar period to the present, with various fluctuations—Dexameni was a symbol of grand bourgeois Athens, but it was once very different. Its social composition was unique. Kolonaki began to develop around 1860 at a slow pace. The first houses were modest, humble, single-story or two-story structures with courtyards and chicken coops. Very few of these remain today, living monuments of an entire era. Almost all the streets were dirt roads, like Patriarchou Ioakeim, which was then called Kynosarges.

After 1880, construction became denser, and the social fabric changed. The construction of Vasilissis Sofias Street (then Kifisias) played a significant role, along with the establishment of the royal court, ministries, and other organizations around it. In Kolonaki, members of the royal court, ministers, politicians, high-ranking government officials, businessmen, and other affluent citizens rushed to settle, as it was near the center of power of the time and the concurrently developing commercial center.

It was then that the construction of luxurious mansions and grand residences began, especially on Vasilissis Sofias and on many other streets in Kolonaki, designed by famous architects of the time. Many of these still adorn the area today. Gradually, as in all of Athens, horse-drawn carriages were replaced by the first automobiles, trams, and later buses and trolleybuses, leading us to the current traffic chaos of millions of vehicles of all kinds and the metro system.

Thus, Kolonaki gradually transformed into the aristocratic center of Athens, becoming the point where politics, diplomacy, arts, culture, science, the past, the present, and the future converged.

In the post-war period, Kolonaki became identified not only with the social elite and the financially prosperous Athenians but also with intellectuals and artists. They chose to live there or to spend their time in its popular spots. From Varnalis and Papadiamantis to Hadjidakis, Giannis Tsarouchis, Melina Mercouri, Alekos Sakellarios, Jenny Karezi, and Aliki Vougiouklaki.

Kolonaki is home to many significant museums: the Benaki Museum, the Museum of Cycladic Art, the Byzantine and Christian Museum, and the War Museum. Additionally, the Hatzikyriako-Gikas Gallery on Kriézoti Street, as well as many historical galleries such as Kalfaian, Zouboulaki, Skoufa, and others. There is also the Marasleios Academy, the Gennadius Library, and the Moni Petraki. Embassies such as the American, British, and French, among others. Top hospitals such as “Evangelismos,” the largest in the Balkans, NIMTS, and the Naval Hospital. Moreover, there are historic monuments with significant emotional weight, such as the headquarters of the Gestapo on Merlin Street 6, as well as EAT-ESA.

With a Delay

Although since the years of the Interwar period Kolonaki had become an expensive area and a residence for high incomes, the luxury shops corresponding to the status of the political, intellectual, and economic elite of the capital who frequented there arrived with a delay. Initially, as in other neighborhoods of Athens, the usual shops dominated—small and even working-class establishments: grocery stores, fruit shops, butcher shops, dairy shops, barbershops, pharmacies, paint shops, bakeries, etc. Then came the sweeping current that swept away almost everything in its path, bringing luxury retail stores, fashion houses, restaurants and bars, jewelry shops, and so on.

The older residents nostalgically remember this beautiful neighborhood when it was still aristocratic. Some residents, not a few, under the weight of the influx from every corner of Greece, the emergence of many nouveaux riches, and the traffic congestion, guided by the philosophy of the well-known song “we are all the same in this world, the people and Kolonaki,” were forced to leave. Nevertheless, Kolonaki remains popular, the top neighborhood in Athens. It withstands the ravages of time, self-renews, discovers new strengths and possibilities, and continues to have devoted residents as well as visitors who still uphold its prestige today.

The Naming of Streets

A major challenge for Athens at a time when it was an expansive farmland, and simultaneously a vast plot with prospects for development, was the naming of streets and squares. The city began to expand rapidly. The streets had to be officially named, and houses numbered. The architects Stamatios Kleanthis and Edward Schaubert took the lead on this difficult task of urban planning. They plotted and named the first 24 streets of the new capital. To begin with, the glorious ancient Greek past served as a rich reservoir of names (such as Ermou, Athenas, etc.).

Many names were retained. In 1837, Mayor Dimitrios Kalifronas, also known as the “foustaneloforos,” decisively advanced the naming of streets. He also opened the way for the numbering of plots and houses, which had until then been done in an incomprehensible manner. The first numbering of newly constructed houses was not done by street but by the city as a whole. For instance, if a property in Plaka had the number 100, the next property built, whether on Stadiou Street or elsewhere, would be assigned the number 101!

Thiseio – Petralona

Beyond Kolonaki, many neighborhoods close to the center of the capital or even a bit further claim the title of the “navel of Athens” since the time it was declared the capital. Among them are the nearby Mets, Thiseio-Petralona, Monastiraki, while a unique case is Patissia.

In Thiseio, residents were always blessed, as they could gaze upon the Sacred Rock of the Acropolis. In the plans of Kleanthis and Schaubert, when they developed the first city plan, the square that exists today outside the Thiseio station was once a threshing floor. These gave their name to the entire area where the popular Thiseio and, of course, Petralona, which is divided into Upper and Lower Petralona by the Electric Railway lines, are located.

In Lower Petralona, there were the second goat markets of Athens—implying due to the multitude of stables that existed. Shepherds with their goats roamed all over Athens, selling the milk they milked on the spot. Since 1920, for public health reasons, this practice has been strictly prohibited.

At the borders of Petralona, as well as in other areas, such as Elaiona, where the new stadium of Panathinaikos is currently being built, and elsewhere along the Kifisos River, fierce disputes often erupted. The gardeners and landowners clashed with the shepherds, accusing them of destroying their crops with unchecked grazing.

The solution came from the municipality, which in 1915 prohibited “all having flocks of sheep or herds of cattle and all kinds of animals from grazing within the area of Athens and the Elaiona throughout its entire perimeter,” with the exception of the shepherds of Plaka. Thus, the shepherds were forced to relocate southeast, to the uncultivated lands after Faliro, up to the area of Vari.

The area of Thiseio began to be inhabited after 1821, primarily by Romeliotes and Corinthians. It went through various names. In 1908, it was called Melitis Varathron, likely because it was near the ancient Varathron, a pit where condemned corpses were thrown in antiquity.

After the Great Catastrophe of 1922, when thousands of refugees flooded the capital, 800 refugee families from Antalya and Alanya settled in the old quarry behind the hill of Filopappos. This is why the settlement also became known as the “Attaliótika.”

The refugees occupied the hill and, using planks and sheets of metal, built a small shantytown overnight. The police would demolish the shacks, but they would rebuild them. Their settlement became known as Asyrmatos, named after the Naval Wireless School that was located to the west of the Filopappos hill. A shantytown in the heart of Athens, where the refugees lived isolated for several decades.

The shacks of the legendary Asyrmatos were partially destroyed in 1944 during the December events. In the 1950s, at the initiative of Queen Frederica, stone houses were built, known as “Frederica’s Stones,” which housed the refugees. It was the poor neighborhood that the press referred to as “the most picturesque misery,” and it was made into a film by Alekos Alexandrakis.

Today, the area enjoys a second life, with wonderful residences, traditional tavernas, and bars.

Mets, on the Banks of the Ilisos

In another legendary photograph from 1875 taken from Lycabettus, with Kolonaki in the foreground, the Ilisos River appears in the background with its famous bridge, before the construction of the magnificent Panathenaic Stadium, which was to host the first modern Olympic Games in 1896. The Ilisos even had an island, Batrachonisi, a lush flat strip of land between the two banks of the river. It stretched from the Olympic Swimming Pool at Zappeion to the Presidential Mansion. On this island, there were sacred sites from antiquity and Christian churches. In more recent years, the area remained undeveloped until around the 1870s when the “Paradise” theater, the first in Athens, was built, followed by various cafes.

Across from the Zappeion and on the outskirts of Kallimarmaro lies Mets. During the Turkish occupation, at the highest points of the Ardittos hill, there were the windmills of Georgakis that supplied Athens with flour. The only surviving windmill was demolished by its owner in 1986.

In 1872, the brewery “Mets” was established in the area, owned by Karolos Fix, son of the Bavarian Johann Fix, founder of the well-known brewery. The name “Mets” was given in honor of the capture of the eponymous French city by the Bavarians in 1871 during the Franco-German War.

By the end of the 19th century, the area was referred to as “Pantremeniadika.” It was the rendezvous for weddings, as well as a place where Athenians lived out their clandestine loves. In the early years of King George I, wooden shanties hosting recreational centers were found in the area. Many couples, especially married ones with illicit affairs, frequented these centers to avoid prying eyes.

In 1908, the Athens Municipal Council decided to divide the city into four sections—somewhat like districts—and these into 68 neighborhoods. Forty-two neighborhoods retained their names, while 14 were proposed to be changed, and new names were given to others that constituted the city’s expansion. Among those proposed for renaming was “Pantremeniadika” or Mets, which was designated as the Ardittos neighborhood. Due to the concentration of scholars, artists, students, and others, Mets was often referred to as the “Montmartre of Athens.” Today, it is a very beautiful and expensive area.

Focusing on Monastiraki, also in the shadow of the Acropolis, and with the axes of Aiolou and Athinas, the central market of Athens developed. This area originally belonged to the Chalkokondylis family, who also had their mansion there.

Aiolou and Athinas

Above Hadrian’s Arch stood the demolished house known as the Old Stratona, formerly the konaki of Hadjali Haseki, which operated as a prison during the early post-war years. Dominating the square is the Tzistarakis Mosque, built in 1759, which now houses the Museum of Folk Art.

Aiolou was the first street in Athens to be asphalted in 1905, by decision of then-mayor Spyros Merkouris. This was followed by the roads on either side of the Municipal Theater. The works were carried out by the English company The London Asphalt Co. at a cost of 20 francs per square meter. The paving was extended by another company to the streets of Athinas, Stadiou, Panepistimiou, and Omonia Square.

The project sparked the interest of the residents, as it drastically changed their daily lives. Consequently, newspaper articles analyzing the usefulness of the roadworks, the advantages and disadvantages of the asphalt paving, were frequent. Carriage drivers protested because their vehicle wheels slipped dangerously on the new road surface. Similarly, porters had difficulties as their job was to carry well-dressed ladies across the street to avoid mud and dust.

Aiolou Street was also designed in 1833 by Kleanthis and Schaubert. Its other distinction is that it was first paved with gravel in 1860. Along its length, the first inns of the capital operated, as well as the first real Greek hotel with beds and food in 1835. The famous “Aiolos,” at the corner of Aiolou and Adrianou, still stands today and was recently put up for sale at an initial price of 18 million euros.

At the intersection of Aiolou and Vyssea, Spyridon Pavlidis opened his “Glykysmatopoiieion,” the precursor to the chocolate factory that later housed the large factory in Piraeus. There, in 1861, the first chocolate in Greece was produced.

Today, Monastiraki is one of the most popular destinations for hundreds of thousands of Greek and foreign visitors. It is a vibrant area that “never sleeps,” filled with restaurants, bars, and various shops, with real estate values skyrocketing. Eirinis Street runs through Monastiraki, which has repeatedly ranked among the top ten most expensive streets in the world. Who would have believed that back then?

The Square of the Agamon

Until the interwar period, Patissia was an attractive countryside destination for Athenians. It began with King Otto and Amalia, who frequently headed to the sparsely populated but green area in their royal carriage.

In Amerikis Square, at the border with Kypseli, which was formerly known as Agamon Square, the horse-drawn tram stopped in 1887. There was a small café frequented by a group of mature single Athenians. It became a place of protest for the unmarried men shortly before the bankruptcy of 1893, when the state attempted to tax them similarly to those who frequented brothels! Unofficially, it was also called Antheesterion Square, as Athenians celebrated May Day there.

Another area of Patissia, the Kypriadou neighborhood, also known as “Alisida,” was created at the end of Patissia Street around 1920. It was an ideal spot for Athenians’ strolls but had problematic access due to the so-called “beast,” namely the electric railway.

With dense vegetation, fragrant gardens, streams, and other natural beauties, Patissia was a unique area of Athens. Until 1900, it was considered a holiday destination with large agricultural areas and crops. It was inhabited by the middle classes and was a characteristic expression of the late urbanization of Attica. Today, it is one of the most densely populated areas, struggling to maintain its character.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions