“This is why I write. Because Poetry begins where Death does not have the final word. It marks the end of one life and the beginning of another, which is the same as the first but reaches far deeper, to the utmost boundary the soul has been able to explore, at the borders of opposites, where Sun and Hades touch. It is the unending journey toward the Natural light, which is Reason, and the Uncreated light, which is God,” wrote Odysseas Elytis in Open Papers, setting forth his vision that far surpassed the existing norms, though he was among those who fought at great personal risk on the front lines of the Albanian Epic.

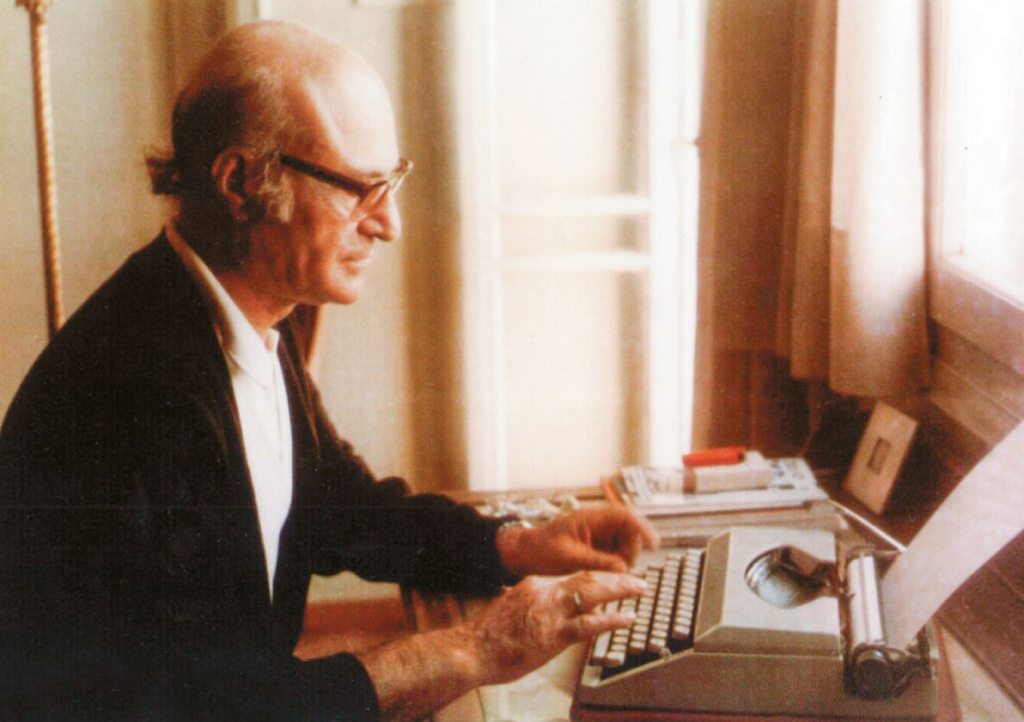

He was also the one who declined the titles of academia, who refused to enter politics, and who, ironically, was translating lines by the freest spirit he had encountered in his homeland, Sappho, in his small 50-square-meter apartment on Skoufa Street on the day of the coup on April 21, 1967. Items from that home, personal belongings, his desk as it was then, texts, and parts of his archive have now been relocated to the new Elytis House – Museum, located at 4 Dioskouron Street and Polygnotou Street in Plaka, which opens on November 1, the eve of the poet’s birthday, in the presence of Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis.

“A Lyrical Genesis”

The museum-house’s inauguration comes at a critical time when Elytis’s thoughts and vision seem more essential than ever. As the curators of the space, primarily Ioulita Iliopoulou, who oversees the organization and archival material, emphasize, the aim is to make his words and poetry resonate once again, as they “offer a powerful counterbalance to the ongoing degradation of many of our core principles.” This museum in Plaka thus seeks to introduce visitors to the poet’s world and his “lyrical genesis,” under the auspices of the AERTON – Elytis Archive Non-Profit Civic Company. According to the curators, the museum is structured along two key axes: to convey information about the poet’s life and work—including the invaluable exhibit of his complete writing desk—and to immerse visitors in the poetic experience through personal engagement with the space and original documents.

Based entirely on Ioulita Iliopoulou’s private collection, which includes visual artworks, objects, books, and various archival materials of the poet, the museum is organized into the following thematic spaces:

The Poet’s Desk

Here, visitors can explore a brief timeline showcasing the main milestones of the poet’s life and work, summarizing the nine decades of his life. By browsing through various excerpts of his writings alongside archival material, manuscripts, artworks, and personal objects, they will gain insight into the poet’s world and his literary workshop, understanding the core themes of his poetry and examining how these connect with other art forms. They will also encounter his primary influences and discover his favorite works. A little further on, in the inner ground-floor room, Elytis’s desk stands out, arranged exactly as it was in his Skoufa Street home. Notably, Elytis used the same desk from his student years throughout his writing career, embodying the simplicity, austerity, high aesthetic, and distaste for anything superfluous that defined him.

Besides his desk, the same room houses the poet’s living room furniture, including a traditional Skyrian sofa, a coffee table repurposed from an old painted chest, and his library, designed by Yannis Moralis, which holds around 700 titles from Elytis’s personal collection. The room is also decorated with artworks that once adorned the walls of his apartment.

On the museum’s upper floor, visitors find a multifunctional events hall equipped with a classical piano and sound system, ideal for future musical performances. Here, too, is a library containing various editions of Elytis’s books, related studies, translations of his works, and two elegant bookcases filled with mostly French literature, offering a glimpse into his personal tastes and serving as a resource for researchers. Visits to Elytis’s archive and library can be scheduled by request through an online form. The Elytis House is housed in a building owned by the Ministry of Culture, operating with its support; the Minister has announced that it will be open from Thursday to Sunday.

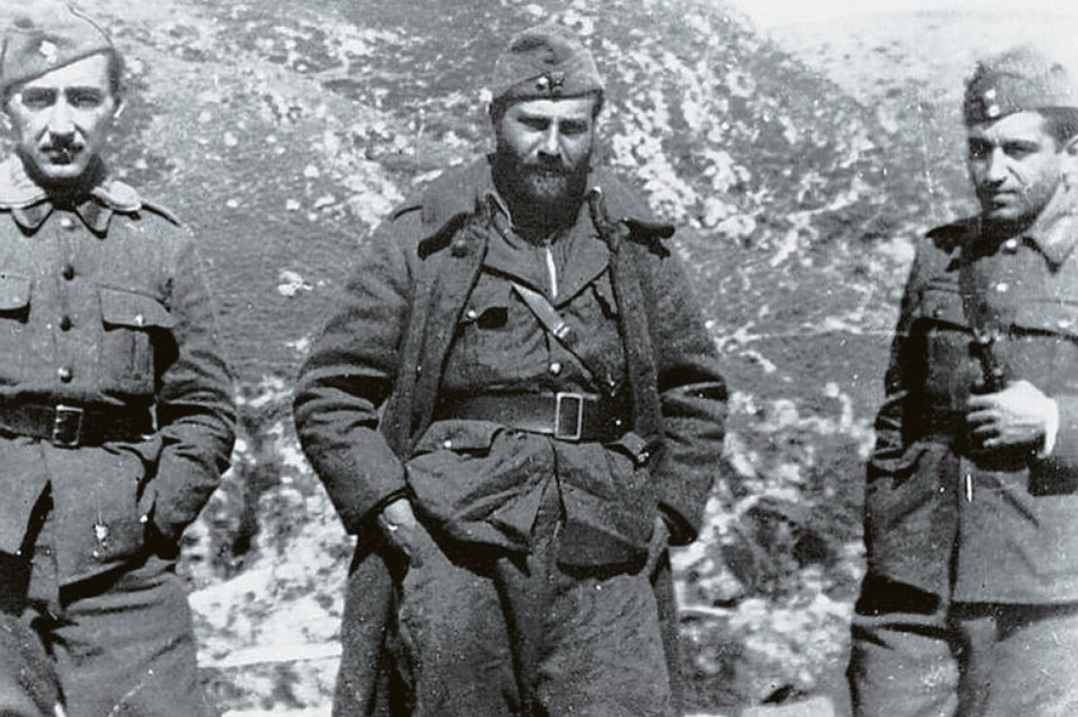

The Albanian Epic

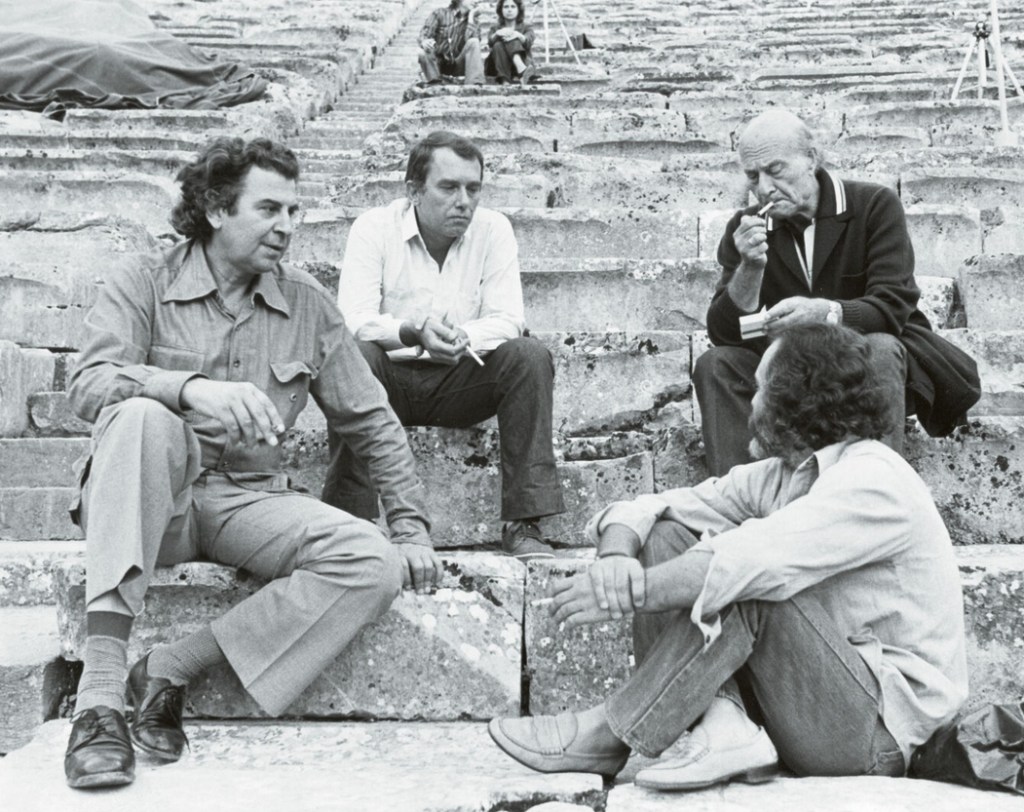

Each excerpt from Elytis’s work serves as a powerful invitation to reflect on our place in this land and reassess our values. “My foundations are in the mountains / and the mountains are lifted by the people on their shoulders, / and atop them memory burns, / an unburnt bush. / My people’s memory is called Pindus, and it is called Athos. / Time shudders / and hangs days from its feet, / emptying with a crash the bones of the humiliated,” Elytis writes in his unparalleled Axion Esti, emphasizing the vital importance of collective memory in the struggle for freedom and the need to keep alive the images of the ‘40s Epic, in which he himself served as a second lieutenant. For the poet, the War of ’40 symbolized the Passion endured by the people on their path toward the much-desired Resurrection, which led him to intertwine the stages of Christ’s Passion with the journey of the Greek people, crafting a poem that is both celebratory and mournful yet undoubtedly grand. When Mikis Theodorakis first read Axion Esti one afternoon at the legendary “Loumidis Loft,” he was so moved by lines like “One swallow,” “The blood of love,” “I open my mouth,” “Sun of Justice,” and “Temples in the shape of the heavens” that he immediately decided to set it to music, saying these verses “drew him like magnets.”

His elevated poetry found the musical accompaniment it needed to be sung by thousands who identified with the lyrics, making this magnificent poem inextricably linked to the consciousness of an entire people. The different stages of war that Elytis experienced at the front lines, where he miraculously escaped death, mirrored the stages of suffering endured by Greece from the liberation front to the Civil War, reflecting the spectrum of emotions that haunted the Nobel laureate throughout his life. It is these painful memories from the Albanian Front that later compelled the poet to express catharsis through the countless gifts bestowed upon him by Greece: the light, the grandeur of the Aegean, and the scattered poetic innocence.

Frozen December

What is certain is that Elytis never forgot the images from the Albanian Epic and the fire zone where he found himself in December ’40. He had already been drafted, like most Greeks, on October 28, serving as a second lieutenant in the Headquarters of the First Army Corps. In November, the headquarters moved to Kalambaka and Metsovo. On December 11, the poet found himself at the front line of the war, and by Christmas, he was stationed at the Kallarates – Bolena line. “What was I doing there? I was just a damaged child of Athens, who with immeasurable effort managed to be simply consistent with my mission,” he humbly stated in an interview with the student magazine Panspoudastiki in 1965 when asked about his role at the Front. He added that he saw “in the faces of my soldiers the glow that Hellenism can radiate when it believes in its cause. And I came to know closely the defiance of death, the unyielding will to live, which ultimately became mine.”

Life at the Albanian Front was far from easy, not only due to the battles but also because of the conditions in which the soldiers lived: frostbite, lice, hardships, typhus—an ailment that struck the poet and required him to be hospitalized in Ioannina. The doctors had almost given up on him, even calling a priest to hear his confession, which he refused, insisting that he would win this battle. And indeed, this was not the only fight he had to face in his life: the column in which he participated from Ioannina to Agrinio was bombed eight times by Stukas, leaving him severely wounded. He could barely walk when they left him on a ledge and departed. He managed to escape thanks to the timely intervention of a nurse who cared for him—doctors noted that if he had been moved, he would have suffered from internal bleeding and died. Once again, he was saved by a miracle.

As he noted in his “Self-Portrait”: “Albania was an unbearable adventure for my physical existence, but for my spiritual history, it was a deep incision […] the war made me realize what struggle means, a collective struggle now, not a personal one. I mean what it means to fight as part of a group with certain ideals and to fight for them too.”

Heroic and Funereal Song

It is precisely from the depths of war that he envisioned the great power of “we” and the eternal value of Light and Sun as the quintessential symbols of resistance for a nation. This inspired his poem that heralded the other major works to come, titled “Heroic and Funereal Song for the Lost Second Lieutenant of Albania.” “Beneath the five cedars / without other candles / lies in the scorched cloak; / Empty the helmet, muddy the blood / to the side the half-finished arm / and among the brows / a small bitter well, the fingerprint of fate / a small bitter well, red-black / well where memory cools! / Oh! do not look, oh do not look where / from where his life has gone. Do not say that / do not say that the smoke of his dream rose high / thus one moment, thus one moment / thus one moment left the other / and the eternal sun thus at once the world!” he wrote evocatively of those days.

In addition to the “Song,” Elytis also wrote inspired by the Albanian Epic and his participation in it, the Albania and Barbaria. Notably, Albania was not published but was staged by Nikos Gatsos as a radio broadcast in October 1956 from the Athens Radio Station, recited by Thanos Kotsopoulos and Mitsos Lygizos, with music by Manos Hadjidakis. This fact remains largely unknown to the public, as does the existence of Barbaria, which remained forever hidden, unpublished, and now destroyed. His narrative in The Journey to the Front stands as one of the most powerful poetic testimonies of the Albanian Epic: “Night upon night we marched endlessly, one behind the other, all blind. With great effort peeling a foot from the mud, where at times it sank all the way to the knee. Because it often drizzled on the roads outside, as it did in our souls. And the few times we paused to rest, we barely exchanged words, only serious and silent, lighting a small lamp, sharing the raisins one by one. Or sometimes, if it was convenient, we hurriedly loosened our clothes and scratched ourselves furiously for many hours until the blood ran. How the lice had climbed up to our necks, and that was more unbearable than the fatigue. Finally, at times the whistle could be heard in the dark, a sign that we were moving again, and like the sheep we dragged forward to gain ground before dawn and become targets for the planes. Because God didn’t know about targets or such things, and as was his custom, at the same time every day the light dawned.”

He Escaped by a Miracle

These are images from the war that will haunt Elytis forever, even when he departs for Paris, the center of thought and the arts. After the war, during the outbreak of the Civil War, he would find himself in the crosshairs, just like Andreas Empeirikos, supposedly for expressing the bourgeois class—coming from the well-known Alepoudelis family, industrialists from Lesbos. Once again escaping by a miracle, he would have the opportunity, upon moving to Paris, to transmute these painful images into a consciousness of the Greek fate and to present the Greek experience as a universal identity. There, he would meet the Surrealists with whom he would have an immediate connection, socializing with Joan Miró, Albert Camus, Tristan Tzara, and Pablo Picasso, to whom he dedicated the text “Ode to Picasso.”

As he himself wrote: “My stay in Europe made me see the drama of our land more clearly. There, the injustice that haunted the poet sprang up more vividly. Gradually, these two merged within me.” It was then that the blood of love dyed him and led him to gradually assume the role of the poet-prophet. He knew every minute detail that illuminated poetry and his own country, which he transformed into materials for an endless, unique staging, where Greece was the sole protagonist. “If you dismantle Greece, in the end, you will find a single olive tree, a vineyard, and a ship. Which means: with just that much, you can rebuild it,” is the legendary phrase that has become synonymous with our national consciousness.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions