“The Athens metro is nice, but the one in Thessaloniki really doesn’t… exist,” the Macedonians used to joke until recently, mocking the continuous delays of a project that never seemed to finish. However, the jokes are over. After delays lasting more than a century, Thessaloniki finally has its own metro.

Simulation tests have started, and on November 30, the residents and visitors of the northern Greek city will be able to take the metro to work, home, or for a stroll, proudly claiming that it is the most modern metro in Europe.

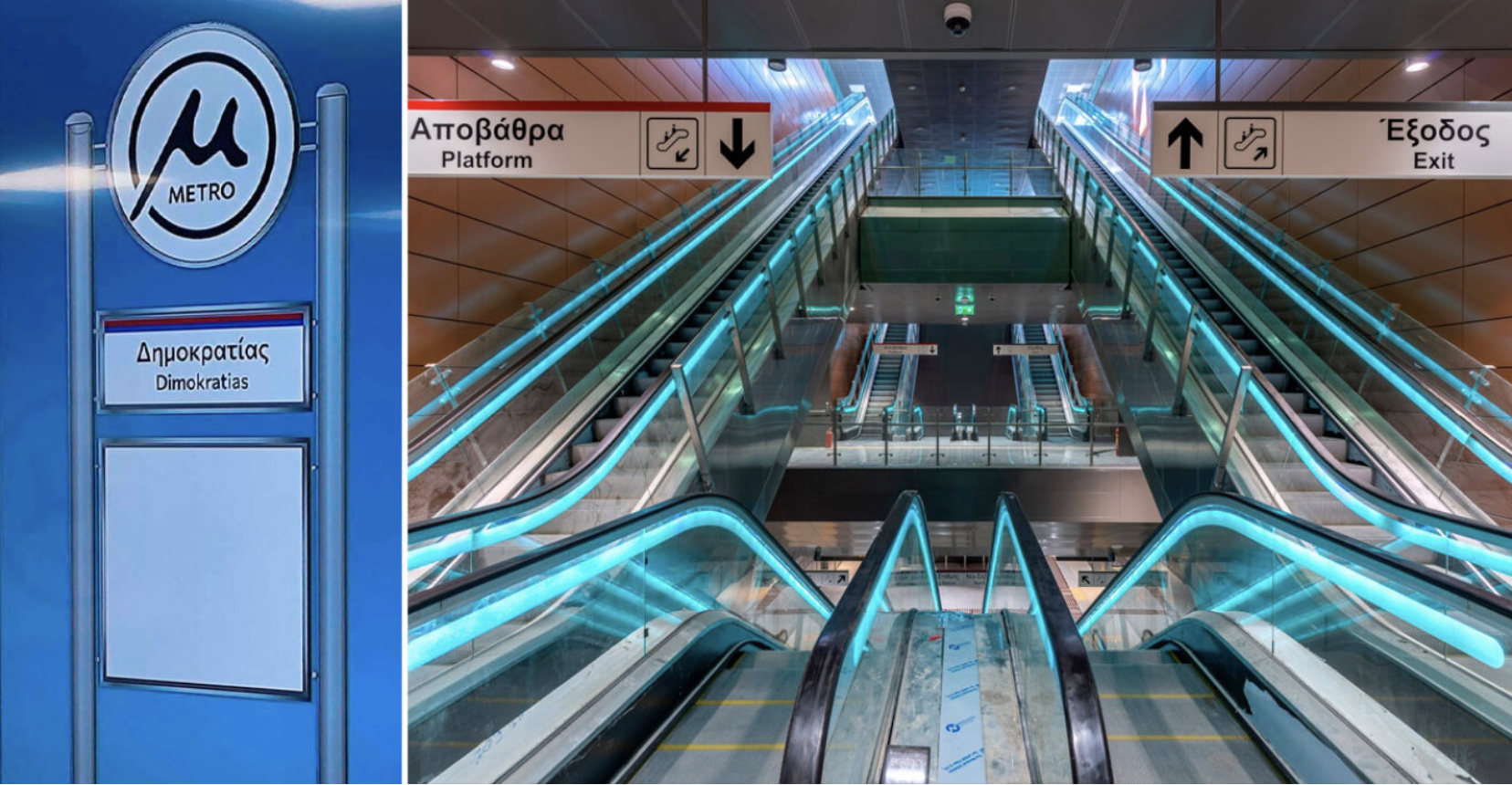

On Wednesday morning, the logo of the Thessaloniki Metro was revealed, featuring a lowercase “m” inside a circle that resembles the tunnels of the metro. This logo is meant to capture the history of Thessaloniki and tie it to the present era through a modern form of mass transportation like the metro. The logo combines the past with contemporary, minimalistic aesthetics, which is why the lowercase “m” was chosen, as it can also be read as an uppercase “M,” explained the head of the architectural department of Hellenic Metro, Chrysoula Kousteni.

With a unique world-first station that doubles as an archaeological museum, driverless trains, and many innovations, the metro promises to improve the lives of the residents of the Nymph of the Thermaic Gulf. How will this happen?

Driverless Trains

Let’s start with the basics. The Thessaloniki metro is 9.6 kilometers long, with 13 stations and a depot where the trains will be stored after service, covering a total area of 55 acres in the Pylaia area. The trains will run with 18 state-of-the-art, driverless, fully air-conditioned trains. For maximum passenger safety, automatic doors have been installed on the platforms of every station, preventing access to the tracks.

In the initial phase, train intervals between stations will be about 3.5 minutes, and later they will become more frequent. Eventually, it will take about 1.5 minutes to travel between two stations. The waiting time at the station until boarding will initially be 2.5 minutes (which will be reduced to 90 seconds with the addition of 15 more trains). Every day, 18 driverless trains will operate at an average speed of 30 km/h, covering the distance between terminal stations in 17 minutes and carrying 18,000 passengers per hour per direction. It is estimated that 313,000 passengers will be served daily, which is expected to relieve the city’s traffic problems.

And this is because, with the full operation of the project (the main line and the extension to Kalamaria), 57,000 cars will be removed from Thessaloniki’s roads, which is expected to reduce the carbon dioxide emissions from these vehicles by 212 tons per day. As for the areas it will cover, the metro will start from the center of Thessaloniki and the New Railway Station, passing through Monastiriou, Egnatia, and Delfon streets, ending in the Nea Elvetia area, where it will connect to the Pylaia depot. The stations will be: Nea Elvetia, Voulgari, 25th of March, Analipseos, Fleming, Euclid, Papafi, University, Syntyvrani, Agia Sofia, Venizelou, Dimokratias, and New Railway Station.

Deputy Minister of Infrastructure and Transport, Nikos Tachiaos, explained that the metro will first solve the problem of access to the center of Thessaloniki, which, as he explained, “is a monocentric city and practically allows transfers from buses to the metro at the New Railway Station area and also in the Nea Elvetia area. Additionally, this will make it easier to decongest all the roads leading to the city center, which will allow the Municipality of Thessaloniki to proceed with sustainable urban mobility plans. From this perspective, it is a very important project for traffic.

To a large extent, it depends on how it is fed by bus lines. However, it is a project that will ultimately change the city’s mentality. Because it’s finally coming to an end, and the city is overcoming one of its ghosts.” The Deputy Minister also made special mention of the metro’s safety, emphasizing that it is a “driverless metro” and that “Line 4, currently being built in Athens, will have the same features with different geometric specifications, meaning it will also be a driverless metro.”

In any case, its safe operation is guaranteed by TUV Rheinland, which is certifying its construction and operating company. Also, the operation is guaranteed by the operating company THEMA, which is primarily composed of the French EGIS and the Italian ATM. ATM, in fact, is the company behind the Milan metro, which operates a similar system in the Italian city, and first operated in Copenhagen in 2000.

The extension project towards Kalamaria will include five new stations (Nomarchia, Aretsou, Kalamaria, Nea Krini, and Mikra) with a total length of 4.78 km of underground line. The total cost of the project has been set at 2.082 billion euros – 1.496 billion for the main line and 586 million for the extension to Kalamaria (which includes rolling stock). The ticket price, as announced by the Minister of Infrastructure and Transport Christos Staikouras, will be half of that of the Athens Metro, at a cost of 0.60 euros.

The Surprise Station

Although the metro will be delivered to the public by the Prime Minister with a modest ceremony, the government believes that the mere presentation of the Venizelou station will be enough to draw attention. This station, which Mr. Tahiatos has described as “unique in the world,” “a jewel the city can invest in,” and “an outcome that will surprise,” is one that will surely captivate.

This is because, in contrast to the other stations, which aesthetically resemble those of the Athens metro, the Venizelou station will be unlike anything else. Essentially, it will be a museum station, as passengers will walk next to or over ancient ruins discovered during the construction works, crossing transparent glass bridges to reach the platforms.

Ancient findings were also discovered elsewhere, such as at Venizelou and Agia Sophia in the historic center, at the stations of Syntrivani, University, Fleming, and the Pylea Depot in the eastern part of the city, as well as in the western stations of Demokratias and the New Railway Station. These findings will also be exhibited, but at the Venizelou station, things are different. At this station, which spans 1,260 square meters per level, archaeological excavations uncovered over 3,500 square meters of ruins, revealing all phases of Thessaloniki’s history from the Hellenistic era onward.

Thus, the founding phase of the city of Cassander was revealed, developed according to the Hippodamian system, following the same road axes with minor shifts. The Hellenistic and Roman central road, Decumanus Maximus, was also uncovered, as well as a Byzantine street, and a significant architectural complex from the late antiquity urban fabric. The archaeological finds were removed by specialized teams to protect them during construction and were reinstated after the work was completed.

Although the leadership of the Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport is keeping the surprise for the inauguration, we now know that passengers—and even non-passengers—will, upon descending to the Venizelou station, find themselves on the first level below ground, which will essentially be a museum open to the public. On its 1,260-square-meter level, archaeological finds will be displayed in glass showcases, and passengers will be able to walk across glass bridges over the central road of ancient Thessaloniki.

The Ancient Idea

While the Thessaloniki metro project is impressive, even more remarkable is its history, which makes the myth of the Bridge of Arta pale in comparison. Particularly when you consider that the idea for the metro was first proposed in 1918, officially incorporated into the 1976 budget, the first hole (which was never used) was drilled in 1987, and the project was first tendered in 1992.

If this seems excessive, it’s not even a brief summary of the delays, cancellations, and lawsuits that kept Thessaloniki residents waiting to the point where they began to believe the project would never be completed.

In 1918, a year after the 1917 fire destroyed 9,000 buildings in Thessaloniki, British architect Thomas Mawson, part of the team of French architect Ernest Hébrard (who redesigned the city), created a transport master plan that included the creation of a metro. Mawson designed an underground electric railway that would run from the “Vardar” station, as he called it, under Ignatiou Street, all the way to the area of Queen Olga. The master plan for the Thessaloniki metro project was even mentioned in a 1918 issue of The Times Engineering Supplement as one of the city’s major reconstruction projects.

After that, there was silence until the 1960s when some studies were done to assess how the project could be implemented. Nothing concrete started, and the first real hope came in 1976 when then-prefect Konstantinos Pylarinos managed to include a budget code called “Thessaloniki Metro.” However, the result was the same as the previous years, with the exasperated mayor of Thessaloniki, Sotiris Kouvelas, deciding in 1987 to take matters into his own hands.

With no design or agreement with the then-government (which was PASOK, with whom he had a particularly bad relationship), he ordered the drilling to begin. The plan he initiated wanted the metro to run under Egnatia Street, between Koutantzlou Street and Demokratias Square. A tunnel began being dug between Syntrivani Square and the Military Academy.

The problem, however, was that there was no design and no funding, with the mayor pinning his hopes on the newly established municipal television station TV 100, which failed to allocate funds as it was already burdened with the role of the financing body.

Of course, the project—which the mayor defended as a good idea for a “light metro or underground tram, which was much cheaper, would be completed faster, and would serve Thessaloniki well”—was soon halted, leaving behind what the Thessalonians called “Kouvelas’ Hole.” The hole didn’t remain empty, though, as it also flooded the foundations of the Polytechnic School of Aristotle University, which has used pumps to drain the water ever since.

Curiously, the hole has survived to this day (despite the water ingress), with a total area of 3,360 square meters, 8.5 meters wide, 8 meters high, with air ducts and reinforced concrete. A local councilor even suggested it could be used as a nuclear shelter for the city’s residents.

Since the “Kouvelas Hole” led nowhere, the Greek government seriously took on the Thessaloniki metro for the first time, tendering the project in 1992 with co-financing and a concession agreement. Everything seemed to go well, with two provisional contractors being selected in 1994. But the smiles lasted only two years. The original lowest bidder, the Macedonian Metro consortium, was rejected after its Italian partner, Fidele Construction, went bankrupt, and the consortium changed its shareholder structure. For this reason, the then-Minister of Environment, Planning, and Public Works, Kostas Laliotis, rejected the consortium, and its representative, businessman Prodromos Emfietzoglou, took the matter to court.

The Council of State ruled that the consortium was legally invalid, as its composition had changed from the original. After a 10-month investigation, the European Commission filed the case away, and the minister, after these developments (in 1998, as negotiations began with the second provisional contractor, Thessaloniki Metro S.A.), promised that the concession contract would be finalized in three weeks and passed in parliament.

Eventually, the concession contract was ratified by parliament on April 1, 1999, foreseeing a 16-month period for preliminary works. However, this turned out to be an April Fools’ joke, as the consortium failed to secure the necessary funds by 2002, and the European Investment Bank did not approve co-financing. Thus, the project was canceled.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions