50 years ago, on December 8, 1974, on a sunny Sunday, the Greeks, in seemingly the most democratic way, through a referendum and in a state of full freedom, solved once and for all the question of the form of government. It was a problem nearly inherent in the establishment of the modern Greek state, which had divided the Greek people and had been the cause of many calamities.

The second half of 1974 was dense with political events that decisively marked the subsequent course of Greece. The treasonous coup of the junta in Cyprus, the Turkish invasion that led to the occupation of 38% of the island, the fall of the dictatorship, and the restoration of democracy in the country.

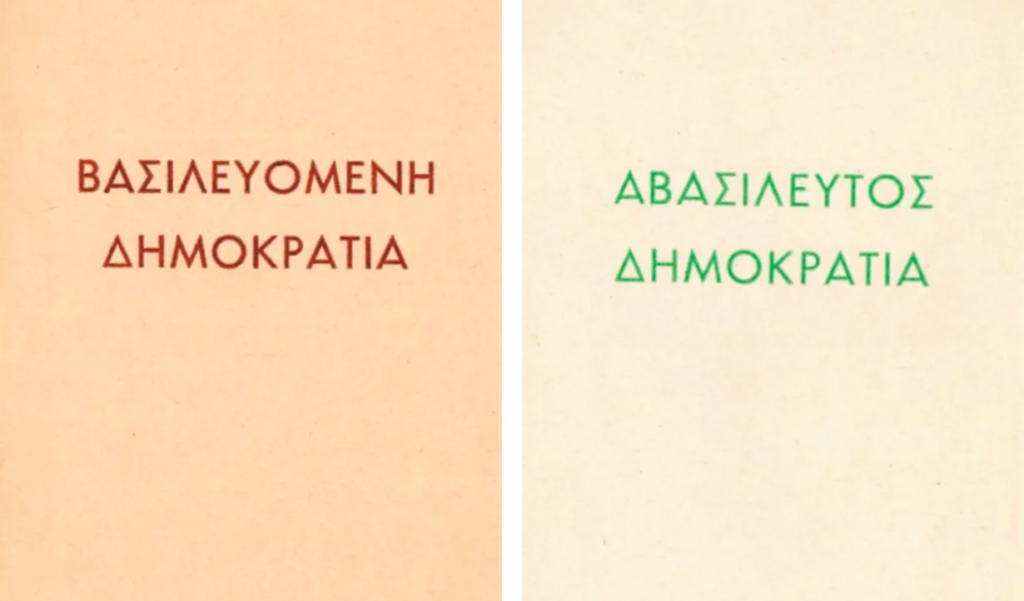

This was followed by the first free parliamentary elections on November 17, in which the New Democracy party, led by Konstantinos Karamanlis, triumphed with 54.37%. Then, three weeks later, a referendum was held, where citizens chose the republican form of government over the monarchical one, with results that left no room for dispute: 69.18% in favor of the republic versus 30.82% for the monarchy. This marked the beginning of the Third Greek Republic.

Five other times since 1920, referendums were attempted to directly or indirectly resolve the question of the form of government, but the division remained unresolved.

However, the key difference of this referendum compared to previous ones was that it was held under conditions of absolute, unprecedented freedom in Greek history, which allowed for an untainted expression of the will of the Greek people and facilitated the acceptance of the result. It thus confirmed the distance between the monarchy and the broader layers of society, where younger generations and emerging social forces, which would later form the core of the changes in the coming decades, played a leading role.

The Palace’s mismanagement of major events, such as the assassination of Grigoris Lambrakis, the political crisis of July 1965, and the legitimization of the junta, made this distance insurmountable.

It is no coincidence that the overwhelming majority of large urban centers voted in favor of the republic. Support for the monarchy was limited to a few of its traditional strongholds, such as Laconia, Rhodope, Messinia, and others.

The wounds did not heal overnight. However, the maturity of the political system and its figures was added to the social background. With leading figures like Konstantinos Karamanlis, Georgios Mavros, Andreas Papandreou, and Ilias Iliou, heading the new parties as well as the old ones that were reconstituted, the political system confirmed its emancipation from the shackles and divisions of the post-civil war period.

The unexpectedly mature stance of Konstantinos played a significant role. It wasn’t just the assurance he gave after his defeat: “National unity takes precedence for the sake of the stability, progress, and prosperity of the country. I sincerely hope that the developments will justify the outcome of yesterday’s vote.”

It was his subsequent overall attitude. He withdrew. He never raised the issue of the form of government again until his death. He did, of course, vehemently contest the Greek state over issues like the fate of the royal property and the name of the family, but never over political issues or the form of government. All of these factors contributed to Greece transforming into a modern Western democracy after 1974, with the undeniable contribution of all the factors that helped shape it.

On the other hand, the 50 years since the referendum find the members of the former royal family living their own lives, a mixture of royal and commoner existence, but far from the stigmas and prejudices of the past and without the subtle moral burden of constantly having to prove that they are not enemies of the political system. Those times are gone for good.

The government of national unity under Konstantinos Karamanlis reinstated the Constitution of 1952 on August 1, 1974, except for the articles concerning the monarchy. The issue of the form of government would be definitively resolved through a referendum within 45 days after the parliamentary elections. On November 22, a Presidential Decree set the date for the referendum to December 8. The political leaders agreed not to intervene in the pre-election campaign.

Karamanlis was strict with New Democracy MPs, instructing them to maintain absolute neutrality: “Each one of us, as an individual, will vote in the referendum unbound and according to our conscience. But it is inappropriate for a member of Parliament to publicly appear, in that capacity, advocating for one or criticizing the other form of government. Because a large party like ours naturally includes supporters of both forms of government.” Those who understand, understand…

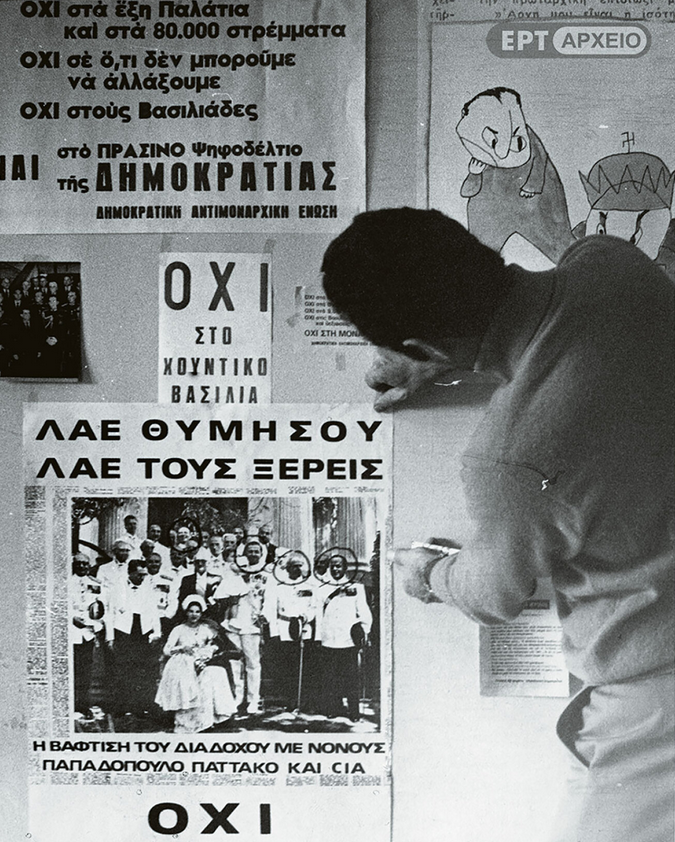

The other parties, except for the pro-monarchy EDE led by Petros Garoufalias, passionately supported the republican form of government. The Democratic Anti-Monarchical Union Committee took the lead in representing this position. Leading figures included the intellectual Marios Ploritis, Alekos Panagoulis, Leonidas Kyrkos, Kostas Simitis, the only living participant in the referendum, and the university professors Phaidon Vegleris and Georgios Koumantos.

They used very harsh tones in their speeches, not only against the institution but also against the person who would embody it. On November 28, Ploritis condemned Konstantinos’ apathetic stance in the events that shook the country: “The seven-year tyranny, the massacre at the Polytechnic, and the tragedy of Cyprus are monstrous offspring of the dictatorship. And the dictatorship is the legitimate and worthy child of Konstantinos.”

They also made it widely known that Konstantinos swore in the first government of the colonels, never condemned – until his removal by the junta – their regime, did not support the Navy Movement in May 1973, and remained silent during the suppression of the Polytechnic uprising, as well as during the coup in Cyprus.

Konstantinos

The supporters of the monarchy were primarily represented by the retired general Sofoklis Janetis. The exiled Konstantinos was not allowed to return to Greece. He was thus forced to express his views through two television messages.

On the black-and-white screens of the televisions of that time, Greeks saw Konstantinos trying to emotionally reach them, stammering some elements of self-criticism for his previous responsibilities: “Undoubtedly, mistakes were made in the past, which led to the weakening of our democratic way of life,” while he appeared willing to accept a new, limited role for the monarchy in Greece.

On December 6, in his second and final television message, he made references to unity: “The king has one desire: To be the king of all Greeks, without any preference for any party, nor for or against any faction.” Nevertheless, the “repentant” Konstantinos did not convince. In an attempt to absolve himself from the past, the figure of his mother, Queen Frederica, was entirely absent from the pro-monarchy campaign.

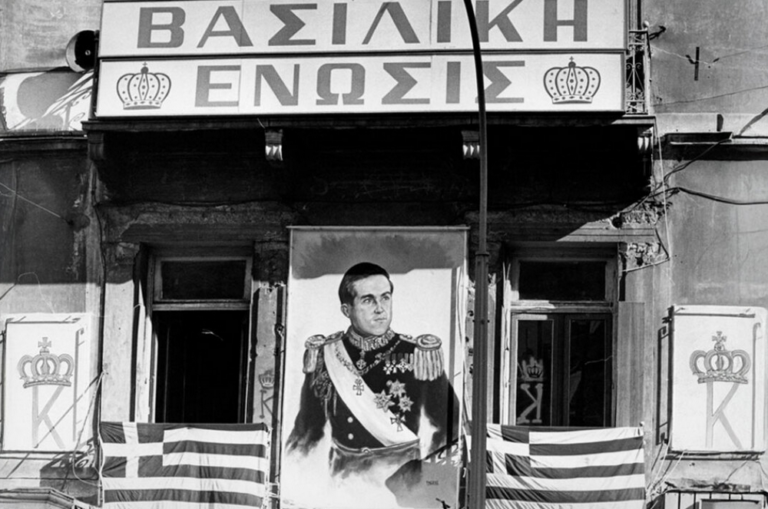

Undoubtedly, Konstantinos’ personal absence from the electoral scene was a significant disadvantage. Instead, the campaign was taken over by the Panhellenic Movement for Monarchy. Its arguments were based on a ten-point list. The dominant theme was that Konstantinos, as king, would be above parties, a guarantor of true democracy, stability, and unity in the country, for a happy future for all Greeks. They argued that he was the first to resist the junta and that this resistance led to his exile, that political instability and conflict were trademarks of democracy, and that the Scandinavian monarchies should serve as a model for Greece.

At the same time, they tried to appeal to the voters of New Democracy by reminding them of previous statements by Karamanlis, in which he had expressed support for a constitutional monarchy before the dictatorship. They also distributed leaflets with a photograph of Archbishop Makarios, reminding the public of an earlier statement by him: “I was, I am, and will remain a royalist.” However, when Makarios spoke at a massive gathering in Syntagma Square on Friday, November 29, during his visit to Athens en route to Cyprus, he seemed to enjoy the anti-junta, but also strongly anti-monarchy slogans from the crowd.

Fanaticism on both sides was pervasive, and the atmosphere often escalated, with posters and leaflets not only containing humorous content, like the iconic cartoon by Spyros Ornerakis depicting a child urinating on the crown, but also heavy insults against the monarchy and Konstantinos personally.

Unfair

The general conditions of the pre-election period of the referendum were unequal, to the detriment of the pro-monarchy supporters. Konstantinos Mitsotakis acknowledged this 14 years later, in February 1988. The then president of New Democracy described the way the referendum was conducted as “unfair” in London. He explained that Konstantinos was unable to conduct a campaign to rally his supporters since he was outside Greece.

After the announcement of the results, there was a popular outburst and celebrations. Karamanlis stated, among other things, that “the people’s decision must be unreservedly respected by all Greeks. And everyone must recognize that the issue of the form of government has been definitively settled.” A much harsher statement was also attributed to him, that “a carcinoma has been cut today from the body of the nation.” But did he actually say that? There is still one point that historians have not fully clarified.

Much later, from Karamanlis’ archives, it was revealed that allegedly Konstantinos, through his aide-de-camp, Colonel Michalis Arnaoutis, had planned a coup in 1975 to overthrow the elected prime minister and restore the monarchy. However, in a meeting with envoys from the Greek government in London, he categorically denied this.

The Royal Property

After his defeat in the referendum, Konstantinos withdrew from public life. He avoided visiting Greece, as he was considered unwanted. The opposing side continuously referred to him as “deposed,” often adding “Glücksburg” in a derogatory manner. Since 1974, he had permanently settled with his family in Hampstead, North London, where he lived until 2013, maintaining close ties with Buckingham Palace.

The death of his mother, Frederica, from a heart attack in Madrid, and especially her burial at Tatoi, became a huge thorn for the Rallis government in February 1981. Citing the risk of unrest, the government rejected Konstantinos’ request for her funeral to take place at the Metropolitan Cathedral and for her burial to be at Tatoi. Everything was carried out in a matter of hours at Tatoi. Immediately after the ceremony, which was attended by members of royal families and about 200 Athenians, Konstantinos and his family left.

A major point of friction with the Greek authorities was the issue of the royal property. The junta had confiscated it by decree and had provided compensation of 120 million drachmas. The members of the former royal family refused to accept it. Later, the Karamanlis government entrusted the management of the property to a seven-member committee. During Papandreou’s government, there were negotiations between the two sides, but they led to no results.

In 1991, the Mitsotakis government reached an agreement with Konstantinos on the matter. The majority of the property was transferred to a non-profit foundation in exchange for the return of the Tatoi palaces and 4,000 acres of the estate to Konstantinos, the settlement of tax liabilities, and the right to export a significant number of movable assets from the country.

Thus, Konstantinos exported nine containers with items from Tatoi to Britain. Some of them were later sold to collectors and auction houses. In 1994, the Papandreou government annulled the agreement with a law. It removed all of Konstantinos’ immovable property in Greece.

A lengthy judicial dispute followed. The former royal family appealed to the civil courts and then to the Council of State. The Supreme Court and the Council of State disagreed. The issue was referred to the Supreme Special Court, which ruled the legal provisions constitutional. On October 21, 1994, Konstantinos and eight members of his family appealed to the European Commission of Human Rights in Strasbourg regarding the property, citizenship, and the right to a fair trial.

In October 1998, the Commission accepted the property aspect of the complaint as admissible but rejected the other claims. The case was referred to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), which in November 2002 condemned the Greek state and awarded the applicants €13.7 million, as opposed to the €500 million claimed by the family. The amount was collected by the Tax Office of Acharnes in March 2003, paid from the natural disaster budget.

With the 1994 law, Konstantinos and his family were stripped of their Greek passports and citizenship. A special procedure was also established for acquiring Greek citizenship, with the condition that all would unequivocally recognize the parliamentary republic as the form of government, renounce any titles, and declare their name – necessarily abandoning the composite “of Greece” – to be registered in the municipal registries. In this same law, Konstantinos was referred to as Konstantinos Glucksburg. He refused to choose a surname, arguing that he had never had one.

Konstantinos visited Greece again with his family in 1993, touring Mount Athos, Florina, Spetses, and Tatoi. After the judicial dispute was concluded, his visits to Greece increased. From the spring of 2013, Konstantinos and Anna-Maria lived permanently in Porto Heli.

In November 2015, his three-volume autobiography was published, in which he recounts and analyzes the events he played a central role in, from his own perspective.

In the final years before his death, he faced serious health problems. His last public appearance was in the center of Athens on the afternoon of Wednesday, October 19, 2022, when he had lunch with Anna-Maria and his sisters, Sophia and Irene, at a well-known restaurant. He passed away at the age of 82 on January 10, 2023, while being treated in the ICU of the “Hygeia” hospital following a severe stroke.

His body was placed in public viewing at the chapel of the Athens Metropolitan Cathedral. The coffin was covered with the Greek flag, and thousands of citizens came to bid him farewell. The funeral service and burial on January 16 were attended by the entire family and 187 official guests, including reigning monarchs and others. On the shoulders of his three sons and grandchildren, he was taken to his final resting place, near the graves of his parents in Tatoi.

Anna-Maria, who had been by his side for 59 continuous years, now spends most of her time in Athens, is president of the currently inactive foundation bearing her name, and frequently attends social events and charity galas.

Pavlos and Marie-Chantal

Fifty years after the dramatic events of ’74, the life of Constantine and Anna-Maria’s descendants unfolds within the same framework and coordinates they inherited from them. They live as princes and princesses, holding honorary titles—thanks to the internal protocol of royalty worldwide—enjoying all the privileges of high visibility, but also exposed to its dangers.

They are not known for the vulgar display of wealth, and, combined with their constant rejection of scenarios that would have had Pavlos or Nikolaos either striving to restore the monarchy or leading pro-monarchist parties, they seem to enjoy a sympathy from public opinion that Constantine never experienced. Or perhaps indifference. But not hostility.

As professional technocrats, art enthusiasts, or supporters of initiatives through the foundations they are part of, or, finally, as prominent members of the international jet set—often sons-in-law of magnates—they generally occupy the public eye positively, both individually and collectively.

Most of Constantine’s children chose to live permanently abroad. Pavlos, born in Tatoi, lives with his wife Marie-Chantal Miller, daughter of American Duty-Free mogul Robert Miller, between New York and London since their marriage in 1995.

Having studied Law and Administration at Georgetown University in Washington, he worked at the Charles R. Weber shipbuilding company in Connecticut and later co-founded investment companies in New York. Marie is a graduate in Art History from New York University and today designs luxury children’s clothing lines and writes books.

The 57-year-old Pavlos identifies as Greek, expresses complaints about the loss of his Greek citizenship, and rejects the surname Glucksburg. The couple has five children: Maria-Olympia, Konstantinos-Alexios, Achilleas-Andreas, Odysseas-Kimon, and Aristeidis-Stavros.

The 28-year-old Maria-Olympia is perhaps the most famous member of the entire family, with 300,000 followers on social media, magazine cover shoots, and collaborations with top fashion houses (D&G, Louis Vuitton, etc.), often captivating the public with her real or rumored relationships.

Konstantinos-Alexios, or Tino, is involved in directing; Achilleas-Andreas—known as Aki Miller—having studied Literature and Ancient Drama, is pursuing a career in acting; and 23-year-old Odysseas-Kimon is a fashion designer.

“Greece Runs Through My Veins”

Nikolaos holds a degree in International Relations from Brown University in the U.S. He has extensive experience in the banking sector and as a business consultant. Recently, he has dedicated himself to photography, holding exhibitions in London, Doha, and Melbourne under the pseudonym Skylightchaser. He is also a special advisor to Axion Hellas since its foundation in 2016. “Greece runs through my veins. I am Greek, and no one can dispute that. If there’s a will, I am not responsible for the surname; we’ll figure it out,” he often says. The 55-year-old Nikolaos married Tatiana Blatnik, of Slovenian-German descent, in 2010. They were the only family members to have chosen Athens as their permanent residence. Tatiana, especially known for her philanthropic work and several public appearances, was considered one of the most beloved couples in Greek society. Thus, news of their separation last spring caused a stir.

The youngest of the former royal family, Philippus, was born in London in 1986 and was baptized at the Cathedral of Saint Sophia with distinguished godparents: King Juan Carlos of Spain, Prince Philip (husband of Queen Elizabeth), and Diana, Princess of Wales.

With a degree in International Relations from Georgetown University in Washington, in 2018 he met Nina-Nastasia Flor, the only daughter of Swiss entrepreneur Thomas Flor, founder of VistaJet, a company that operates a fleet of over 70 Bombardier jets, and Katarina Flor, a former executive at Fabergé and Russian Vogue. Nina was the creative mind behind VistaJet and is also the owner of the luxurious “Kisawa Sanctuary” hotel on Benguerra Island in Mozambique.

They got engaged during a holiday and the pandemic in Ithaca in the summer of 2020 and married twice: on December 12 with a civil ceremony in St. Moritz and on October 23, 2021, with a religious ceremony at the Athens Metropolitan Cathedral. The couple owns one of the most expensive apartments in Athens, a 320-square-meter property on Herodou Attikou Street, a gift from Nina’s father, and engages in charitable activities.

Alexia, the eldest child of the former royal couple, moved to Barcelona in 1992, studied as a kindergarten teacher, and worked with children with Down syndrome. She lives in her husband Carlos Javier Morales Quintana’s homeland, Lanzarote, the largest of the Canary Islands, in a house-mansion overlooking the sea. The couple has four children.

Their two older daughters, Arietta and Anna-Maria, are students and synchronized swimming athletes. At their grandfather Constantine’s funeral, they carried his medals and honors. The other two younger children are Carlos and Amelia.

The 41-year-old Theodora was born in London. She holds a degree in Theater Arts from Brown University and lives and works permanently in Los Angeles, where she met her husband, Matthew Kumar, a lawyer specializing in natural disaster compensation. She pursued a career in acting and had a leading role in the famous “The Bold and the Beautiful.” After several postponements, the couple married at the Athens Metropolitan Cathedral on September 28 this year, in one of the most popular social events.

Sophia and Irene

Among the surviving members of the former royal family, Constantine’s sisters Sophia and Irene stand out.

86-year-old Sophia, the eldest of all, studied childcare, music, and archaeology and speaks five languages fluently: Greek, Spanish, English, French, and German. She married the heir to the Spanish throne, Juan Carlos, on May 14, 1962, in Athens, converted to Roman Catholicism, and declares herself 100% Spanish.

After Franco’s death in 1975, the monarchy was restored, and Juan Carlos was proclaimed king, with her becoming queen. Since 2014, she holds the title of Queen Mother as the mother of the current king, Felipe.

Since 1998, she has increased her official and private visits to Greece. By her husband Juan Carlos’s side for nearly four decades, she has paid a high price for rumors about his extramarital affairs. The family has been estranged for years. Juan Carlos has been living in exile in Dubai for the past four years under the shadow of financial scandal charges, although they have now been dropped.

Meanwhile, problems have also arisen in the relationship between Sophia and Letizia, Felipe’s wife, with public evidence of their coldness toward each other. Sophia engages in extensive charitable work and fully supports her granddaughter, Princess Leonor, the future queen of Spain.

The relationship between Sophia and Irene represents a bright example of true sisterly love and solidarity. Recently, Princess Irene, who previously battled breast cancer and overcame it, is facing another challenge: cognitive decline. Sophia plays the central role in caring for her, managing everything. The 82-year-old Irene, with a career as a pianist, followed Constantine into exile.

Later, she lived for some time in India and for many years in Athens, in a small apartment in Mavili Square. She consciously chose to remain out of the public eye, and despite her beauty, one of the most sought-after royal brides of her time, she never married or had children. Sophia affectionately refers to her as “Aunt Pekou” (short for “peculiar”).

Ask me anything

Explore related questions