For the past three years, Europe has had its eyes fixed on the conflict between Russia and Ukraine. Many may think that only the two World Wars have left deep marks on the history of the Old Continent. However, a deeper reading of European history reveals a surprising truth: it is filled with wars, most of which were prolonged conflicts. A prime example is the Great Northern War (1700–1721), which shifted the balance of power in Northern Europe. Sweden, once the dominant power in the region, suffered a decisive defeat by Russia—then known as the Tsardom of Russia or Muscovy—which, by 1721 under Peter the Great, emerged as the strongest nation in Northern Europe.

The Great Northern War (1700–1721)

By the mid-17th century, Sweden had become a powerful empire, controlling nearly all the territories bordering the Baltic Sea. Among them was Russia, which, due to a treaty signed in 1617, had lost all access to the Baltic—the primary European trade route. When the 15-year-old Charles XII ascended to the Swedish throne in 1697, Sweden’s neighbors saw an opportunity to defeat their aggressive and expansionist rival.

They were wrong. Charles XII was not a weak monarch but a courageous, hardened, and determined leader. A small yet telling detail: Charles learned Latin solely to read “The History of Alexander the Great” by the Roman historian Quintus Curtius Rufus. This fact is worth noting for those who underestimate the Macedonian conqueror. Charles XII remains an idol abroad but a controversial figure in his homeland.

The Road to War

By late 1699 and early 1700, the monarchs of Denmark-Norway, Saxony (ruled by Augustus II the Strong, also King of Poland-Lithuania), and Russia formed an alliance against Sweden. Charles XII responded by launching a swift counterattack. He first struck Denmark, forcing his cousin, Frederick IV, into submission. He had naval support from Britain and the Netherlands, who wanted to keep the Øresund Strait open to trade.

He then turned to Russia. Swedish General Dahlberg forced the Saxons to lift their siege of Riga (now the capital of Latvia but then under Swedish control). Charles launched a daring attack on Russian forces at Narva in Estonia, navigating treacherous marshlands and launching a surprise assault during a snowstorm. Despite having only 8,000 troops, he annihilated a vastly superior Russian army in November 1700. His generals urged him to march on Moscow to finish Peter off, but Charles, wary of the harsh Russian winter and the unfamiliar terrain, hesitated—a decision he may have later regretted.

Next, he invaded Poland. By May 1702, he captured Warsaw, then won a decisive victory at Kliszów in July. He took Kraków, defeated the Saxons and Poles again at Pułtusk in April 1703, and conquered the historic city of Toruń. In 1704, he installed Stanisław Leszczyński as King of Poland, sparking a civil war. Augustus II attempted a counterattack, but in the Battle of Fraustadt (1706), Swedish forces crushed the Saxons, Poles, and Russians. Charles then invaded Saxony, seizing Leipzig and Dresden, forcing Augustus to abdicate the Polish throne.

The Russo-Swedish War: How Did We Reach the Battle of Poltava?

Following his defeat at Narva, Peter the Great restructured his army along European lines, even adopting elements of the Swedish military model. While Charles was preoccupied with Poland, Russian forces recaptured Ingria (northwestern Russia) and in 1703 founded Saint Petersburg. By 1704, they had retaken Narva.

Despite Peter’s repeated peace overtures, Charles refused any settlement that did not restore Sweden’s pre-1700 borders. Determined to eliminate Russia as a threat, he launched an invasion with 35,000 troops, reinforced by 12,500 men under General Lewenhaupt from Livonia. However, he had to leave strong garrisons in Sweden, Poland, Finland, and other Swedish territories.

In July 1708, Charles won a major victory at Holowczyn (in present-day Belarus) against a Russian force three times the size of his own. He considered this his greatest triumph. He then continued toward Moscow, winning smaller engagements. Meanwhile, Peter intercepted Lewenhaupt at Lesnaya, inflicting heavy losses and seizing essential supplies bound for Charles. This defeat left Charles with only 6,000 reinforcements, most of them weakened by hunger.

Charles turned south to Ukraine, seeking supplies. However, Russian forces implemented a scorched-earth strategy, depriving the Swedes of resources. In Ukraine, Charles found an unexpected ally in Ivan Mazepa, the Cossack leader, who, after being denied aid by Peter, switched sides. Around 3,000 Cossacks joined Charles. In October 1708, Charles and Mazepa signed a pact: Sweden would support Ukraine’s independence, and Charles vowed not to negotiate with Russia until Ukraine’s sovereignty was restored.

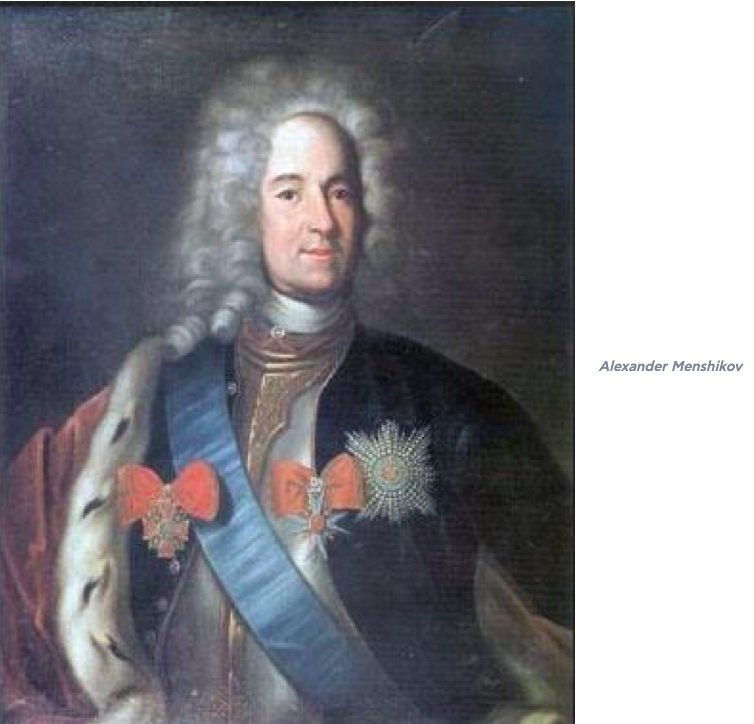

Peter reacted swiftly. His commander, Alexander Menshikov, sacked Mazepa’s capital, Baturyn, and massacred its inhabitants, deterring many potential Ukrainian allies. Charles, undeterred, marched on Poltava, where Peter had fortified his army of 45,000–49,000 men (some sources claim 80,000) with 130 cannons. The odds were stacked against Charles.

The Battle of Poltava (June 1709)

The winter of 1708–1709 was brutal, with the Rhône River in France freezing and even the canals of Venice icing over. Disease and starvation reduced Charles’ army to 23,000–31,000 men. Knowing that Mongol Kalmyk reinforcements were en route to aid Peter, Charles rushed his attack.

On June 28, 1709 (Old Style), Charles was inspecting outposts when a Russian bullet wounded him in the foot. Confined to a stretcher, he delegated command to Generals Rehnskiöld and Lewenhaupt, who disagreed on tactics. The planned night attack was delayed until dawn, losing the element of surprise.

Initially, the Swedes advanced, appearing poised for victory. However, Peter’s newly modernized artillery, based on Swedish models, inflicted devastating losses. Charles, carried onto the battlefield to boost morale, could not turn the tide. By 11 a.m., the battle was over. More than 6,900 Swedes lay dead, 2,800 were captured. Russian casualties were 1,345 dead and 3,200 wounded. Peter also seized valuable Swedish military assets, including banners, drums, trumpets, and weapons.

Aftermath: Charles XII in Didymoteicho

Following his defeat, Charles and a small force fled to the Ottoman Empire, seeking refuge in Bender (modern Moldova). The Ottomans initially supported him, but after five years, he was forced to return to Sweden. On his way back, he stayed for several months in Didymoteicho, a key town in the Ottoman Balkans. He would later die in battle in 1718.

The Battle of Poltava marked the end of Sweden’s era as a great power and heralded Russia’s rise as the dominant force in Northern Europe—a legacy that endures to this day.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions