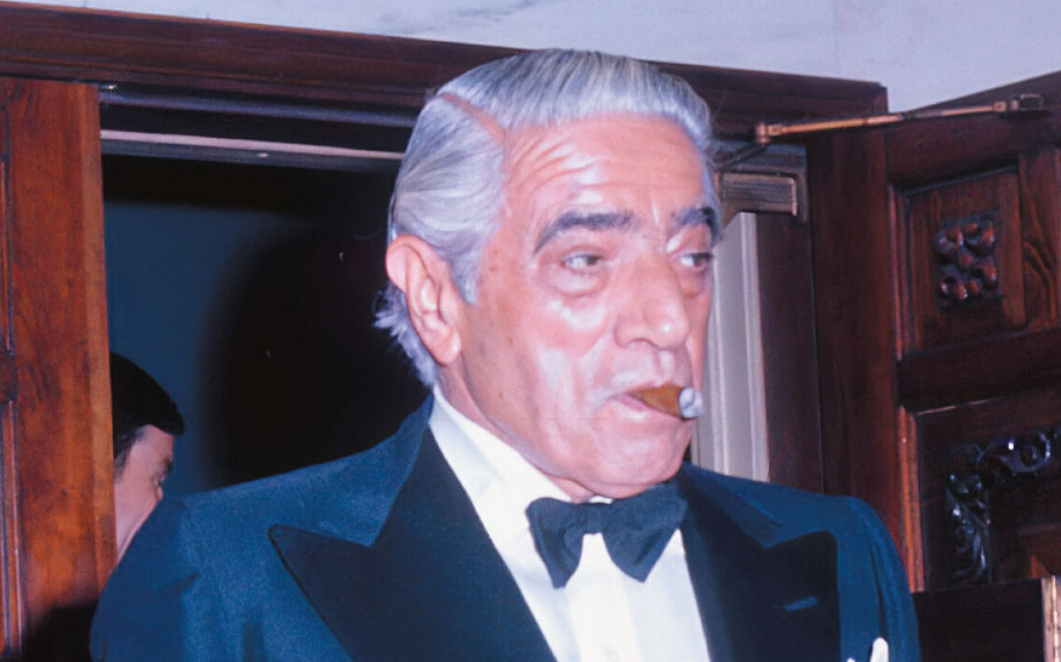

It was Saturday, March 15, 1975, exactly 50 years ago, when Aristotle Onassis took his last breath at the American Hospital in Neuilly, near Paris, succumbing to acute myasthenia. He was undoubtedly the most famous and recognizable Greek across the globe during the period from 1950 to 1975—the epitome of a global tycoon, whose tremendous legacy echoed through subsequent generations, remaining unexpectedly intense and influential even today. A figure bordering on myth. A Greek who embodied the dream of worldwide success, yet remained firmly rooted in his homeland and Greek identity. The Greek dream.

His name became synonymous with wealth—at a time when there was no “Forbes” list, only the everyday perception of affluence—and with business acumen. Yet, he never provoked envy or resentment among ordinary Greeks, who, on the contrary, mostly admired him for his achievements. This excluded, of course, some of his fierce competitors, particularly in the shipping industry.

A man with a multifaceted personality—often a blend of contrasting elements, defined by delicate and fluctuating balances that shaped a different image of him at different times. At times unconventional and disruptive, aggressive in his business dealings, as well as in his relationships with women. Both aristocratic and popular. From high society salons and the opera to the grand stages of Greek nightlife, the bouzouki clubs, and drinking ouzo in seaside tavernas. More often than not, he was impulsive, tempestuous, and insatiable, guided by a philosophy of “give and take” even in his personal relationships, though at times he could be reserved and conciliatory. Emotional, yet also a realist to the point of cynicism when he deemed it necessary—and he often did. In any case, he wrote a unique chapter in Greece’s post-war history: the first tycoon of Greek and global shipping.

(With his first wife Tina Livanou and their two children, Alexandros and Christina)

From Smyrna to Athens

“A Penniless Onassis”: The title of a 1970s comedy film starring Kostas Voutsas, about a salaried employee who shares the famous last name and gets into various misadventures because of it. No other Greek film ever equated extreme wealth with the name Onassis.

Urban legend has it that Onassis started out with nothing before conquering the world. Is that true? Onassis was indeed self-made, in the sense that he built a true empire on his own. He had the vision, seized opportunities, took risks, dared to innovate, and overcame threats and dangers to reach the pinnacle of success.

However, he did not start from absolute zero. He was born on January 15, 1906, in the aristocratic district of Melantia in Smyrna. His father, Socrates, was a wealthy tobacco merchant. His mother, Penelope, passed away in 1910. “If she had lived, I might not have worked so hard in my life,” he later confided.

He had an older sister, Artemis, and two half-sisters from his father’s second marriage to Eleni Tzortzoglou—Meropi and Kallirhoe. He attended the Evangelical School of Smyrna and, in 1922, was forced to flee with his family from Smyrna due to the Asia Minor Catastrophe, eventually arriving in Greece under dramatic circumstances.

Argentina

At the age of 17, with only a few dollars in his pocket, Onassis left for Argentina, traveling under a Nansen passport in search of his own fortune. In Buenos Aires, he worked various jobs—from dishwasher and waiter to night-shift telephone operator—while learning Spanish and scanning business news for opportunities. At one point, he made $800 from a stock tip. He spent it all on silk shirts and luxury suits. Investing his meager savings in commodity indices, he managed to make some additional money.

His first business ventures followed his family’s footsteps in the tobacco trade—a plan originally devised by his father, who aimed to export tobacco to Argentina. Onassis imported Oriental tobacco, which was lighter than Cuban and Brazilian varieties. He targeted a new market: female smokers. He even set up a cigarette factory but later abandoned it, focusing exclusively on trade.

(With Maria Callas. Their relationship was stormy, strengthening the legend of both)

Breakthrough

By the time he was 25, rumors claimed he had already made his first million dollars. That may not have been entirely accurate, but even if it was, Onassis chose not to risk all his money on a single venture. Instead, he turned to shipping, realizing that in 1932, a ship’s cost could be repaid with just three months of freight earnings. He purchased his first steam-powered cargo ships for £3,775 each. Half of the money was his own, while the rest came from bank loans, arranged through Dracoulis Shipping in London.

He eventually acquired four cargo ships from the National Steamship Company of Canada, which had been laid up in the St. Lawrence River. He raised the Greek flag on them and named two after his parents—Onassis-Penelope and Onassis-Socrates. Thus, the legendary career of Greece’s greatest shipping magnate was launched across the Atlantic.

(With Churchill, who vacationed on the “Christina” from 1956 and for all subsequent summers)

Inge and Entry into Shipping

“The rule is that there are no rules” and “The secret to business is knowing something no one else knows”, were two of his favorite mottos. He combined sharp business acumen with an unparalleled instinct.

Business and women dominated his life—often intertwined as defining moments in his turbulent journey. “Without women, all the money in the world would be meaningless,” he once said, revealing his guiding philosophy. According to Onassis, every woman he approached was a potential lover. He believed that “the best deals and the best sex happen beyond limits”, and that when the two combined, he would experience—and did experience—ultimate satisfaction. Whether this brought him true happiness remains debatable.

It was no coincidence that the first significant woman in his life was Ingeborg Dedichen—known as Inge in elite circles—the daughter of a Norwegian shipping tycoon. Five years older than him, twice divorced, they met in December 1933 on the Italian steamship Augustus, traveling from Buenos Aires to Genoa. She introduced him to Europe’s most exclusive resorts and high society, as well as the whaling industry, in which her father excelled.

Through Inge, Onassis ventured into newly built ships and the oil shipping market, becoming the first Greek to invest in tankers.

He ordered a massive 15,000-ton oil tanker from Gotaverken Shipyards in Gothenburg—far larger than the 9,000-ton maximum of the time. He received it in June 1938. It was the world’s largest tanker, named Ariston, and was chartered to Jean Paul Getty’s Tidewater Oil Company for oil transport between the U.S. and Japan. He followed this with another, Aristophanes, and nearly completed a third, Buenos Aires (17,500 tons), before World War II disrupted his operations.

In 1939, he founded his first Panamanian company, Sociedad Maritima Miraflores Ltd., in London, transferring his ships under the Panamanian flag. From then on, he consistently used offshore companies and flags of convenience. He later admitted that this decision caused him “pain in the soul”—but it generated immense profits.

By 1940, he had settled in the U.S. and purchased two additional second-hand tankers. By 1945, he owned six.

(In October 1968, Onassis married Jackie, widow of JFK)

Tina and the Great Leap

He gained such confidence that in 1946, having divorced Inge, he proposed marriage to the top Greek shipowner Stavros Livanos’ daughter, the 17-year-old Athina (Tina). They married on December 28, 1946.

This was the second major milestone in his life. It marked his official entry into the Greek shipping lobby, which viewed him with suspicion and hostility. It also excluded him from acquiring a fair share of the 100 surplus Liberty ships that the U.S. had allocated to Greece under the Ship Sales Act of 1946 as compensation for wartime shipping losses. Despite playing a leading role in the approval process, he only secured 14 ships. This was the beginning of a “cold war” with many of his Greek shipping peers. Enraged, he wrote an extraordinary letter—dubbed the “Onassiade” by The Times—where he used numerous nicknames for specific shipowners, calling them “sharks,” “ulamades,” and others, not even sparing his father-in-law. He also proposed ideas on how Greek shipping could dominate globally.

Ten years later, his fleet had skyrocketed to 77 ships totaling 791,324 Gross Registered Tons (GRT), placing him at the top of international shipowning. By 1965, he had more than doubled his fleet to 1.5 million GRT, with nearly the same number of ships, and by 1975, he reached 2.5 million GRT.

How Did He Do It?

Every obstacle he encountered, he almost always managed to bypass. With the help of American law firms and banks, he circumvented regulations and built a fleet of 12 Liberty ships and T2 tankers under the authorization of the U.S. Maritime Commission. Foreseeing the potential of German shipyards, he placed an unprecedented order for 18 tankers. In 1953, he built the first supertanker in Kiel, a 46,000-ton vessel. The following year, he launched the even larger Al-Malik Saud Al-Awal, named in honor of Saudi King Saud, reflecting a groundbreaking agreement with him.

Under this deal, Onassis would provide the core of a national Saudi Arabian tanker fleet, which would operate under his control. The newly formed company, Satco, was set to transport a guaranteed 10% of the kingdom’s oil exports for 30 years. The reaction was explosive—Aramco had held a monopoly on Saudi oil production, transportation, and export since the 1930s.

The dispute was ultimately settled by a Swiss arbitration court, which ruled in favor of Aramco. The agreement was voided in 1956, dealing Onassis a severe financial blow, as he had made massive investments in purchasing and building tankers for Satco. Moreover, major multinational oil companies refused to sign transport contracts with him. He even considered selling his entire fleet to Royal Dutch Shell, but fortunately, he did not go through with it.

(Alexander Onassis. After his death, his father collapsed)

The Suez Crisis

Then, luck smiled on him. His near-bankruptcy turned into an opportunity. The game-changer was Egyptian leader Nasser’s nationalization of the Suez Canal. According to Onassis: An Extravagant Life by Frankie Brady, he made more money from this event than in his entire life.

How? Nasser’s move was followed by an Israeli invasion of the Sinai Peninsula. Egypt closed the canal for six months, forcing tankers to take the long route around Africa. Freight rates skyrocketed to unprecedented levels. Onassis was the only shipowner with many vessels available for charter, free from long-term contracts, allowing him to set the rates as he pleased. At the time, the cost of transporting oil from Saudi Arabia to Europe was $4 per ton. Onassis charged over $60 per ton! He made $2 million in profit per tanker voyage. In a single year, he earned the equivalent of $1 billion in today’s money.

Around this time, he had already secured his status as the second most powerful man in Monaco, after Prince Rainier. In 1953, he acquired majority control of the investment company that owned the Monte Carlo casino, the Hotel de Paris, the yacht club, and one-third of the principality’s land.

In 1956, he purchased the Greek airline TAE from the state, giving birth to Olympic Airways, known for its high standards of passenger service. Onassis’ dream was to serve all five continents, as symbolized by the Olympic rings in the company’s logo. He achieved this goal in 1972. “Shipping is my wife, but aviation is my mistress,” he used to say.

Callas and the Peak

At the same time, he entered a passionate relationship with the opera legend Maria Callas. This was not just another milestone but a profound, all-encompassing, and emotionally extreme chapter in his life. Their affair united two of the most famous Greeks of the 20th century, further cementing their legendary status. It also accelerated the final dissolution of his marriage to Tina in 1960, who later married his biggest rival, Stavros Niarchos. By then, Onassis already had two children, Alexander and Christina, ensuring the succession of his empire. But fate had other plans…

Beyond the prestige and the media frenzy, his relationship with Callas fueled Onassis’ already immense ego. It reaffirmed that he could conquer anything he desired. Yet, it also seemed to fulfill a deeper, unspoken longing. Callas had the rare ability to shed her diva persona and transform into a traditional Greek woman for his sake—one reminiscent of his mother in Smyrna, as he remembered her. She cared for him, tended to his needs, and anticipated his desires, which thrilled the emotionally deprived Onassis.

Their love was turbulent and unstable—worthy of films and television dramas. Callas brought out both the best and worst in him. She uncovered his sensitivity and humanity but also his destructive tendencies, as he remained obsessed with wounding those he loved and being drawn to what hurt him.

During the 1960s, Onassis reached the peak of his business empire. By 1975, his total wealth was estimated at $2.6 billion (adjusted to 2020 value). At that time, world-renowned politicians, business leaders, and artists were among his regular guests. Some were invited aboard his ultra-luxurious yacht Christina, while others visited Skorpios, the small, barren island opposite Lefkada, which he purchased in 1963. He transformed it into a private paradise with lush vegetation, guesthouses, small harbors, and pristine beaches.

His two “palaces” hosted figures of Churchill’s stature, Giovanni Agnelli, Greta Garbo, and many others—including Prince Rainier, of course.

(Christina with little Athena)

The Plan for the Athenian Riviera

The original vision for the Athenian Riviera bears Onassis’ signature. The magnate wanted to invest in Greece to contribute to its development. He started with Olympic Airways and expanded into cruise tourism with Olympic Cruises. In 1966, when his ties with Monaco weakened, he proposed a colossal investment to the Greek government—transforming the coastline from Faliro to Vouliagmeni into a resort rivaling the French Riviera. He received no response.

During the military junta, despite disliking the regime, he considered investing in large-scale industrial projects. He drafted the “Omega Plan” for the energy sector, initially allocating $400 million to build Greece’s third oil refinery, an alumina plant, and a power station. He later increased his offer to $700 million. Nothing materialized.

In October 1968, he married Jackie Bouvier-Kennedy. Another fortress had fallen.

The Death of Alexander

On January 23, 1973, Onassis’ only son, Alexander, an exceptional pilot, died at just 25 years old when his Olympic amphibious aircraft crashed at Ellinikon Airport due to a wiring system failure. The loss itself and the lingering questions surrounding the real causes of the tragedy—especially since the two other passengers survived—devastated Aristotle, shattering him emotionally and ultimately affecting his physical health.

In December 1974, Onassis offered $1 million to anyone who could provide proof that Alexander’s death was the result of sabotage. The official investigation concluded that negligence was to blame. However, Onassis was convinced it was a conspiracy, suspecting the CIA and the Papadopoulos regime rather than an accident.

With Alexander’s death, Onassis’ own countdown began. He lost his passion for life, as well as the very fuel that had driven him—his business empire. His designated successor was gone.

This was the final chapter of his life, marked by two contrasting elements: on one side, devastation, withdrawal, and collapse.

The Onassis Foundation

On the other hand, Alexander’s death motivated Onassis to secure his legacy, ensuring his life’s work would not be wasted. Through the establishment of the Onassis Foundation, he became one of the greatest benefactors in modern Greek history. In his final will, he left half of his fortune to his daughter, Christina, while allocating Alexander’s share to create a foundation in his name.

The foundation has two branches: a philanthropic arm and a business arm. The philanthropic sector funded the construction of the Onassis Cardiac Surgery Center, an eight-story facility that took five years to build and cost over $75 million.

Fully completed and equipped, the center was donated to the Greek state on October 6, 1992. Since then, under state management, it has transformed cardiology and cardiac surgery in Greece, facilitating thousands of surgeries and heart transplants.

In addition, the Onassis National Transplant Center (ΩΕΜΕΚ) is now in its final stages of completion. This cutting-edge, four-story hospital, dedicated to solid organ transplantation, has a construction cost of €100 million and is outfitted with €30 million worth of advanced medical technology.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions