As Europe looks for ways to increase military spending against the threat of Russia, Greece offers valuable lessons in what is required when living next door to an adversary such as Turkey. Although the country of 10 million people maintains a strong armed forces regardless of cost, it has struggled to develop a strong domestic defense industry, notes a Bloomberg article.

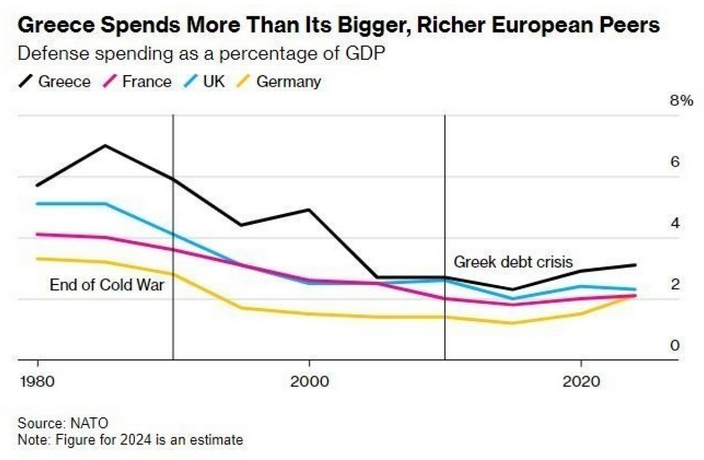

“When the alarm sounds at the military base in Tanagra, northwest of Athens, it takes no more than five minutes for a Rafale fighter jet to take off and head for the Aegean Sea, on the border with Turkey. Greece has a long-running rivalry with its neighbor over sovereign rights to the island waters that separate them. Although they are NATO allies, their forces came close to conflict in 1996 and tensions escalated again just five years ago,” the article says, and continues: Greece consistently exceeded NATO’s target of spending 2 percent of GDP on defense, even at the height of the debt crisis that crippled its economy. In 2015, the year Greece was negotiating tough austerity measures with its creditors to fix its finances, it was still spending more than Germany, France and the UK as a percentage of GDP.

Unlike other parts of Europe, a strong military is deeply ingrained in the Greek mindset. The country is among the few in the European Union with mandatory military service, and spending on national security has traditionally been a policy supported by all governments.

“Greece’s defense structure is primarily geared to deterring Turkey,” said Ino Afentouli, executive director of the Institute of International Relations in Athens and a former NATO official. “There is no other priority.”

“Greece’s geopolitical position is very special, creating many security challenges,” said Spyros Blavoukos, a professor at the Athens University of Economics and Business and a researcher at the think tank ELIAMEP. The geography means the country “is in a constant state of readiness in terms of its defence spending and military equipment programs.” While the Mediterranean nation has invested heavily in buying military equipment, unlike Turkey, it produces little of it domestically. Much of the country’s spending has been allocated to military personnel and the procurement of weapons from abroad, while little has been invested in research and development. This is a missed opportunity, according to Afendouli, something Europe should avoid repeating as countries respond to growing uncertainty about the U.S. role in European security under President Donald Trump’s administration. “If you have a 10-year defense strategy, you have to build a national industry based on what you have,” she said.

The EU’s ReArm Europe initiative to boost security capabilities could also give Greece a boost.

The country has two main state defense companies: Hellenic Defense Systems (EAS), which produces various types of ammunition, and the Hellenic Aerospace Industry (EAB), which supports fighter jets and manufactures aircraft components, including those for the F-16.

EAB, headquartered in Tanagra next to the airbase, is in the process of producing its own drones as well as an anti-drone system, an early version of which was used on Greek warships participating in the recent EU naval mission Aspides in the Red Sea.

“Modern wars have proven that having a domestic defense industry is a necessary prerequisite for maintaining reliable armed forces over time,” said Alexandros Diakopoulos, chairman and CEO of EAB. “You must be able to manufacture certain systems independently so that you can support them without relying on foreign sources.”

The size of Greece’s defense spending as a percentage of GDP is comparable only to that of the U.S. or EU countries that are in close proximity to Russia, such as Poland or the Baltic states. Greece’s commitment to maintaining a deterrent force is also evident in the personnel of its armed forces. More than 1% of the population serves in the military, compared to 0.6% in Turkey, 0.4% in the U.S., and 0.2% in Germany.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions