“When I was a kid, I thought all writers were dead. We had no books in the village, I found some old ones, forgotten on a dusty school shelf… All classic literature from the last century,” protothema.gr laughs, Makis Tsitas, a children’s book author, tells protothema.gr. He, himself, visits schools frequently where he tries to pass on to children the idea of reading as a process of entertainment, pleasure and suggests ideas for familiarizing them with it.

Manos Kontoleon, a writer and literary critic, also speaks to protothema.gr about the importance of cultivating literacy in children based on rules.

April 2 is World Children’s Book Day, a day of celebration chosen by the International Books for Young People (IBBY) on the occasion of the birthday of the great storyteller Hans Christian Andersen. As for the most influential factor in fostering a child’s relationship with books, the educational level of parents emerges as the most influential factor, according to a survey by the Organisation for the Collective Management of Literary Works (OSSDEL).

Makis Tsitas, author of children’s books, advocates the family as the starting point for the cultivation of literacy in children: “It all starts from the home. As imitative beings, children, seeing their parents reading instead of always being on their cell phones or tablets, will pick up a book themselves. I find every day that richer vocabulary, greater clarity of expression, and comfort in communicating are the result of children who read at home.” Next, teachers have the responsibility to instill a love of literature in children, according to him, while he points out the importance of the school library: “It is essential to have a school library – if there is one, children can go with their friends, their best friends to borrow books, to discuss them in a relaxed atmosphere. Ideally, there should be more municipal and public libraries, as is done abroad, for adults as well. In Finland, there are car-mobile libraries that go to even the most isolated settlements to distribute books and come back to distribute others after collecting the previous ones.”

How can children who are unfamiliar with books be brought closer to literature?

“The truth is that you don’t start with Papadiamantis, because today’s child can’t relate. It’s like giving your elderly aunt, who has never read, a gift of a Dostoevsky book. It is better to give the child something contemporary, close to his interests – fortunately, there are books on all subjects, from sports and bands to travel and animals. Children also feel more comfortable when the characters in the book are heroes they know from video games or cartoons.” It is the content that will capture the child’s interest. However, it is equally important that the child understands that this is ‘entertainment’ and that they are not expected to memorise information or write a test on the book they have read. “The aim is for the child to have an enjoyable time with a book,” he stresses.

Personal contact between children and authors is important

The authors’ visits to schools are supportive in helping children to love books. “When I was a kid in the village, we didn’t have books,” he will say. “At one point, I discovered on a dusty school shelf forgotten volumes of classic literature – all the authors from the last century. That’s why I thought at the time that all the writers were dead, I didn’t know there were any living ones!” he adds. “When I visit schools, to be more accessible to children, I dress simply, in jeans and cotton, and I’m more relaxed. After I read the book to them, I talk to them in detail about the whole process of ‘birth’ of a book – from inspiration to the printing press and that’s something that fascinates them. I show them the manuscript, the typescript. I flip through books with hard covers and others with soft covers, so they can hear the differences in the sound of the paper, so that their senses are stimulated. Younger children often ask me, ‘how did the pictures get into the book?’ or ‘How long did I write it in?’. It strikes them that a book is difficult to write, and this is something that inspires respect.”

Family visits to neighborhood bookstores are another of Mr. Cheeta’s suggestions to foster a child’s contact with books, especially if book presentations are held on Saturdays. As for children who may have difficulty concentrating, it is advisable to give preference to books with shorter text and an emphasis on pictures, while it helps to have an adult read while the child is holding the book. For older children, instead of a novel, a switch to short stories may be the solution for them to love books.

In any case, as Mr. Tsitas notes, “the foundations for engagement with literature are also laid in elementary school. If you miss those years, it’s very difficult later to really get in touch with books.”

2 April – World Children’s Book Day

Author and literary critic Manos Kontoleon, talks about the establishment of World Children’s Book Day, which was established by the International Books for Youth (IBY) to be celebrated on the day Hans Christian Andersen was born.

“The aim of the IBBY, which was founded in 1952, is for books to be a bridge to communication and understanding of one another, and this effort should begin in childhood, since what is well planted in the soul of a child and adolescent remains bushy and fruitful for the rest of his or her adult life. In addition to World Children’s Book Day, the IBBY has established the Andersen International Children’s Book Prize – a prize comparable to the Nobel Prize – which honours one author of books for children and young people and one illustrator every two years. In addition, it compiles honorary lists of the best books that have been published in all its member countries within every two years. In each country, the IBBY has its national sections – in Greece, it is the Greek Children’s Book Circle / Greek IBBY”, says Kontoleon.

The author’s view is that literacy will be cultivated mainly at school, provided it is part of a framework of rules. As he explains, “some years ago, when the National Book Centre (NBC) was in operation, a group of university teachers and writers had drawn up a programme of literacy in schools that included the creation of school libraries and the enrichment of them with new titles, and the implementation of various programmes (e.g. visits to schools by authors), as well as the training of teachers and lecturers in the ways of implementing literacy programmes. After the closure of the Hellenic National Book Foundation, the programme was left in abeyance, and those of us involved in children’s and teenage books are waiting hopefully to see how the new body, ELIVIP (Hellenic Book and Culture Foundation), will encourage literacy.”

Regarding how one can turn the interest of a child or teenager towards a good literary book, and especially in an age where images and the internet dominate, “one should make sure to offer them a rich and free choice of literary texts in whose pages the young reader will encounter and recognize situations similar to those he or she is living, characters close to himself or his friends, and certainly all this should be recorded with literary quality and by the aesthetic conditions in which all of us – young and old – live”, he stresses, hoping that “literary reading programmes will be revived in primary and secondary schools”.

The Children and Reading survey by the Organisation for the Collective Management of Literacy Works (CMA)

The research of the Collective Management of Literary Works (CMWL), entitled “Children and Reading”, which was conducted under the scientific direction of Nikos Panagiotopoulos, Professor of Sociology at the Department of Communication and Mass Media of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (2023), highlights the relationship between children and reading and the role of education in shaping this relationship. As the research (osdel.gr) shows, the unequal relationship with reading, which is experienced by children from specific social groups, produces social, cultural, and economic inequalities, a fact that must be remedied through state actions.

The results of the survey

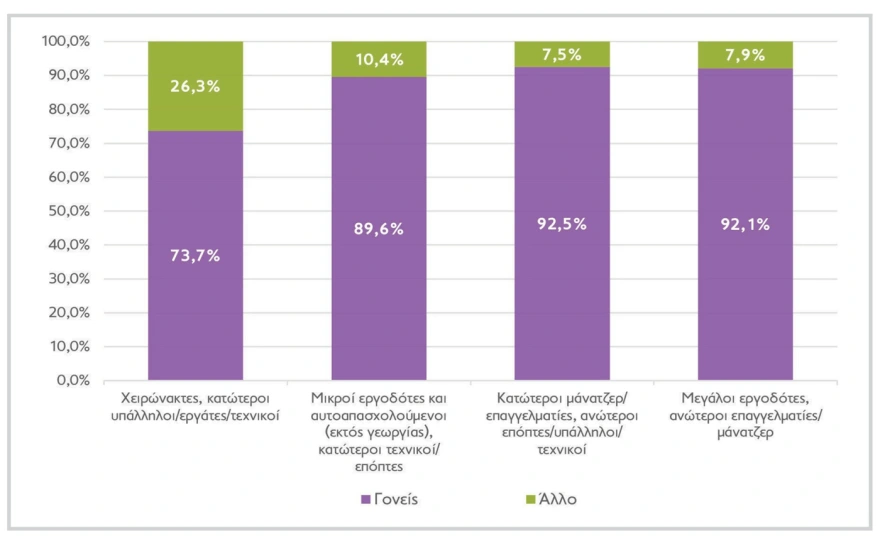

Strongly decisive and qualitative role of the family in establishing a child’s loving relationship with reading, as revealed by the overall results. More specifically, the most influential factor in terms of the child-reading relationship was found to be the educational level of parents.

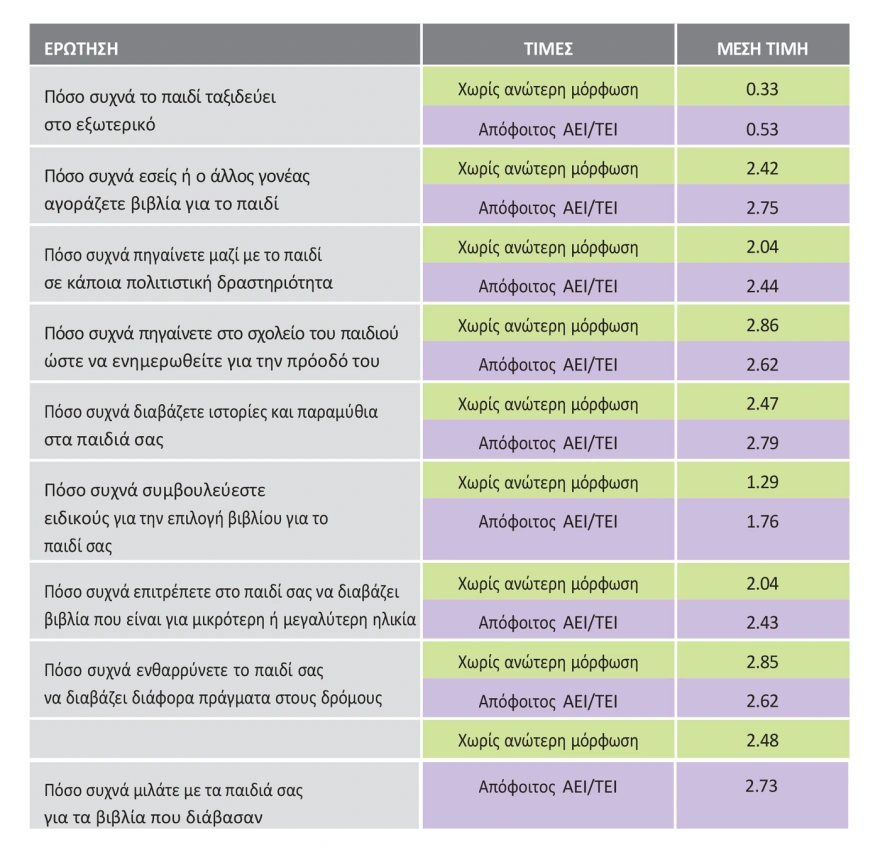

In terms of parents’ educational level, based on the findings, the following seems to be true:

Children of parents with higher education have a closer relationship with reading as they read more books (25.4% read more than ten books per year), more children’s literature (46.1% vs. 40.6%), borrow books from friends or relatives more often (38% vs. 25%), subscribe more often to children’s magazines (11.2% vs. 3.9%), watch their parents read more often (82.8% vs. 72.9%), are exposed less to television (78.1% are exposed for less than one hour vs. 56.8%), and to other screens (63.1% are exposed for less than one hour vs. 49.7%). Also, parents with higher education buy books for their children (2.75 vs. 2.42)2, talk more with them about them (2.73 vs. 2.48), read stories and fairy tales to them more intensively (2.79 vs. 2.47), and also allow them to read books that are for older or younger ages (2.43 vs. 2.04). In addition, parents’ occupation is decisive, but less so than their educational level.

Older children (11-12 years old) seem to do more homework more often (59%) and more private lessons at home (1.05%), usually read one to five books a year (62.9%), read more children’s literature (56.2%), but not as much for fun (45.7%) as other ages (68.7% children 6-7 years old and 57,3% of children aged 8-10), while they are more exposed to screens other than TV (10.5% more than three hours a day and 54.3% between one and three hours) than children in other age categories (77.9% of children aged 6-7 are exposed for less than one hour a day, as are 57.7% of children aged 8-10).

At the same time, their parents perceive them to read less than other age groups, buy them books and supervise what they read to a lesser extent, and play word games with them and encourage them to read things on the street less than children in the other two age categories.

The place of birth of a parent also appeared to have several effects when combined with the parent’s educational level. Children whose parents were born in the periphery were more likely to read more than ten books a year (27.3%), while children of parents from abroad were less likely (13.8%). Parents from the periphery also seem to think that their children read more (2.37), buy them books more often (3.00), which they also comment on more (3.05) – but also talk about them (2.86), give more importance to intensive reading (3.39) and encourage their children to read more (3.17), and read them stories and fairy tales more often (3.14).

Parents in the highest class occupations are much more likely to offer subscriptions to children’s magazines and newspapers to their children (17.5%).

Middle-class occupations tend more often to buy books for their children (2.81 middle and 2.70 middle), supervise what their child reads (3.19 middle and 2.93 middle), and encourage their child to read (3.00 middle and 3.06 middle).

The higher the class level of the other parent’s occupation, the higher the joint participation in cultural activities with the child, and the more often the parents discuss with the child about the books read. When the other parent is in one of the higher professions, parents tend to report that they consult experts more about buying books for their child (1.96).

Regarding the family status of the parent, when parents are cohabiting or married, they are more likely to supervise what the child reads (2.98 vs. 2.59) and encourage the child to read more vigorously (3.00 vs. 2.71), as they consider intensive reading more important (3.23 vs. 3.00), try to be more informed about their child’s progress (2.72 vs. 2.48), read more stories or fairy tales (2.74 vs. 2.36) and talk more about what the child is reading (2.69 vs. 2.38).

Regarding area of residence, parents living in middle-class areas with a traditional intellectual presence all/no parents reported that their child attends private lessons at home (100%), tend to think that their child reads more (3,38), buy books more often (3, 69), encourage their child to read more (3, 38), since they consider intensive reading important (3, 69), and explain unfamiliar words to their child to a lesser extent (2, 92), compared to other areas of residence.

Male parents wish to a greater extent (24.7% vs. 11.8% of females), their child to obtain a doctoral degree. At the same time, they report that their child is taught fewer subjects at home (0.61 vs. 0.84 for women), they supervise less what their child reads (2.62 vs. 2.99), they consider intensive reading less important (2.92 vs. 3.25), they consult experts about buying books to a lesser extent (1.24 vs. 1.68), and they talk less with their children about the books they read (2.40 vs. 2.70 for women).

The educational and occupational profile of parents, grandparents, or grandparents is not systematically correlated with the habits a child develops in relation to reading books.

The conclusions of the OSSDEL survey

As it was found, children become familiar with the concept of reading when the processes of approaching books are “inscribed” in them early on – when you look at them, pick them up, “sit” with them, give them space and time. Similarly, both in everyday pedagogical practice (“finish the whole book”, “look at it”, “put it in the library”), and in the rituals of institutionalizing reading (participation, e.g., in clubs or groups of reading books for children), a psychosomatic action is exerted, often through the emotion evoked by the consumption of reading material.

Also, the child who is consistently and systematically involved in reading practice begins to understand the world of reading very well, experiencing it as his given world, precisely because it is enclosed within him, because he is ‘one body’ with it. The systematic, organized, and as early as possible familiarization with the world of reading makes the child feel at home in the world of the book and the world that contains it, that is, the world of culture, because this world begins to take shape in him at the same time.

In view of the above, the child who loves reading is forged in such a way that no special ‘dictates’ are required, and without even thinking about it, he or she immediately knows ‘readings to be done’ and to be done ‘as and when they should be done’.

In summary, the practice of reading does not have the same social and cultural value for all children. In particular, among parents who foster reading practice in their children, some use reading as a way to put them to sleep, some to develop their use of language, and some to develop their knowledge and imagination.

The sentences

The radically educational and reforming role of the school is considered crucial to the cultivation of literacy.

It is proposed to strengthen the reading practice of children, in order to redress the school inequality by children of different social strata, as differences between the vernacular and school language are recorded. It is found that the spoken languages in different strata are unequally distant from the school language, which is why education must give a very important place, from primary school onwards, to exercises in expressing children’s thinking.

Also noted is the need to staff each school with the same proportion of teachers with different qualifications and the creation of a corps of education assistants, properly paid, who, having special training, will do tutorial-type reading. In addition, supplementary training in the recovery and remedial reading skills should be provided, both during the school year and during holidays. Children from disadvantaged classes should be given special facilities to enable them to benefit. These forms of instruction (or directed tasks) should help children to make up for their particular weaknesses in fast and intensive reading.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions