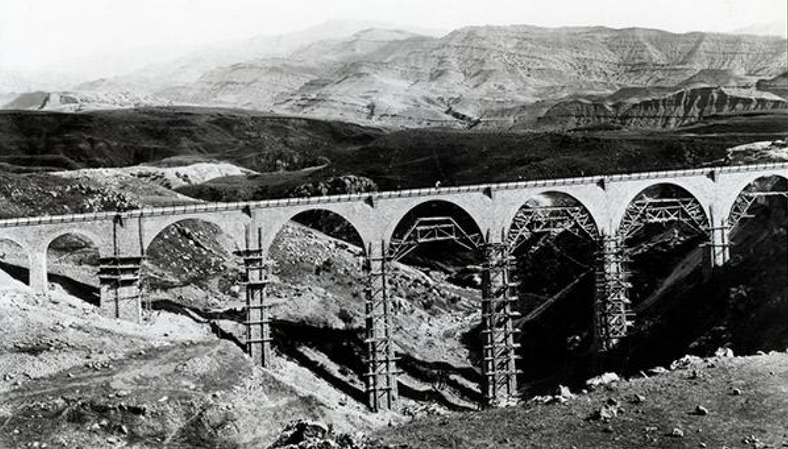

One of the most important railway projects in the world is the so-called Trans-Iranian Railway, which was constructed between 1927 and 1938. It connects the Caspian Sea (in the north) with the Persian Gulf (in the south). It is 1,394 kilometers long and passes through landscapes of incredible beauty. It includes 174 large bridges, 186 small bridges, passes through 224 tunnels, 11 of which are spiral-shaped, and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The project was constructed between 1927 and 1938, initiated by the first Shah of the Pahlavi dynasty, Reza Shah. Many will understandably wonder why we are writing an article about the railways of a foreign country. This is because among those who worked on the construction of this great project were many Greeks, mainly from the famed Mastorochoria (Craftsmen Villages) of the Ioannina prefecture. But also Euboeans and Karpathians (Karpathos, like the rest of the Dodecanese, was then under Italian occupation) had a significant contribution to the construction of the project. Valuable information and rare data are presented in the book “Hellenism in Modern Iran (1839–2010)” (Poreia Publications, 2010), by Mr. Evangelos Venetis, who deserves much praise! The book is now hard to find, and we hope that thanks to today’s article, a new edition will be published, as Mr. Venetis brings to light completely unknown, until recently, facts about Greeks in Iran over the last 170 years (up to 2010).

The decision to construct the Trans-Iranian Railway

Until 1925, Iran had only 418 kilometers of railway lines. The most important line was that of Tabriz–Jolfa, near the northwestern borders with Russia, and it essentially constituted an extension of the Russian railway network. This line was completed in 1913 with the transfer of the initial monopoly from General Falchenhagen to the “Russian Discount Bank of Persia” (Banque d’Escomptes de Perse). The line was extended with Russian funds by 137 kilometers in one year and was handed over to Iran in 1921, expanding its commercial activities with Russia.

However, the line was too small for the increasing commercial activity in the region. Plans to connect Constantinople with the Persian Gulf had existed since 1856 but remained on paper. When Reza Shah ascended to the throne of Iran (1925), seeking to boost national pride and send a message of “economic power,” he decided to construct a modern railway network. Planning for the Trans-Iranian Railway had begun in 1923 by the Iranian Ministry of Roads, in collaboration with foreign advisors. It was eventually decided that Western companies, in cooperation with the Iranian state, would undertake the construction of a 1,394 km railway line that would connect Bandar-e-Shahpur on the Persian Gulf with Bandar-e-Shah on the Caspian Sea. Construction of the project began in 1927 and was completed in 1938. It was a major challenge for its constructors, as the line would pass through mountain ranges, deserts, and cultivated lands, crossing only two cities (Ahvaz in Khuzestan and Tehran).

Construction of the project made significant progress between 1927 and 1929. By the end of 1929, 129 km in the north and 249 km in the south were completed. However, problems that arose with the German and American companies that had undertaken the project temporarily halted construction. A new contract was eventually signed with a Swedish-Danish consortium, which, instead of dividends, created subcontracts for 60,000 workers during peak periods of productivity. The line was delivered for use in 1938, comprising 462 km in the north and 925 km in the south. Immediately afterward, the network was extended, connecting Mashhad and Tehran with Tabriz and the Soviet railway line, but with the outbreak of World War II, expansion stopped, although 50% of the work had been completed. The British Transportation Service, within 15 months, extended the network by 121 km, from Ahvaz to the port of Khorramshahr. In early 1943, the project was handed over to the Americans, who managed it until the end of World War II. The Trans-Iranian Railway cost 30 million British pounds (35,000 British pounds per mile). Its financing came exclusively from Iranian resources: 65% from duties on imported tea and sugar, 20% from state subsidies, and the rest from loans from the National Bank of Iran. It was very important for Iran not to resort to external borrowing, in the aftermath of the 1929 Crash.

The situation in Greece during the Interwar period – The Mastorochoria of Epirus

The economic situation in Greece during the Interwar period was not good at all. The Asia Minor Catastrophe, the arrival of refugees, and the 1929 Crash were the three main reasons for this. The plains and coastal areas managed to cope with the problems better. In Epirus and Western Macedonia, however, the problems intensified. The only solution was emigration. This time, the construction of the Trans-Iranian Railway, which required craftsmen skilled in stonework, offered an opportunity to craftsmen from the Ioannina prefecture, Western Macedonia, Euboea, and Karpathos to work in Iran with good pay.

The people of Epirus, due to the barren soil, the insecurity caused by bandit raids, and the economic underdevelopment, abandoned agriculture and livestock farming and turned to stonework and iconography. Organized into groups (mpouloukia), they soon gained fame beyond the borders of Epirus. They traveled throughout Greece and abroad, creating masterpieces. After finishing their work, some remained in the places to which they had traveled. These craftsmen were known as koudaraioi, and to communicate with each other when they did not want others to understand what they were saying, they used a coded language called koudaritika. Most Epirote craftsmen came from the famous Mastorochoria (Craftsmen Villages) in the Konitsa region, but also from villages in the Tzoumerka area and elsewhere. There is some disagreement about which villages exactly constitute the Mastorochoria. However, almost universally, the following villages of the Municipality of Konitsa are mentioned: Pyrsogianni, Vourbiani, Kastaniani (Konitsa), which should not be confused with Kastaniani of Pogoni, although many believe that the former was founded by inhabitants of the latter who abandoned their village due to raids and famines; Plikati, Chionades, from which the famous Chioniadites, folk iconographers of Epirus, originated; Asimochori, Oxyia, Kefalochori, Theotokos, Drosopigi, Langada, Plagia, Pyrgos, Agia Paraskevi, Amarantos, Pournia, Giannadio, Molista, Monastiri, Agia Varvara, Exochi, Pyxaria, Trapeza, Nikanor, Pigi, Eleftheria, while the settlement of Fourka, although not included in the list of Mastorochoria, had significant contributions of labor to the constructions undertaken by their neighboring villagers.

According to Evangelos Venetis, important Epirote craftsmen also came from villages of Tzoumerka (the Athamanika Mountains): Agnanta, Ampelochori, Vaptistis, Gouriana, Graikiko, Koukoulia, Ktistades, Melissourgoi, Michalitzi, Petrovouni, Pramanta, Raftanaioi, and Houliarades. Mr. Venetis, in his work “Hellenism in Modern Iran (1839–1910)”, mentions that it is unknown how so many exceptional stone craftsmen came to be in one region of Epirus. Legends say that some families from Vourbiani originated from Constantinople. Indeed, the village’s flag bore the double-headed eagle. They began building their mansions in Vourbiani and evolved into the best builders. Pyrsogianni, in its current location, has existed since the late 17th century, and its first settlers came from Constantinople and Macedonia. However, the origin of the inhabitants of these villages from Constantinople belongs more to the realm of legend and less to historical reality.

The Greek craftsmen in Iran

A distinct category was made up of bridge builders, the gefyropoii (kioproulides < Turk. kopru=bridge). After all, the stone bridges of Epirus and Western Macedonia are true architectural monuments.

At the time the construction of the Trans-Iranian Railway began, stone craftsmen were unemployed, as their last flourishing period was in the late 19th – early 20th century. When the project in Iran began, it was not possible for news to reach the mountainous villages of Konitsa. However, in 1935, under unclear circumstances, the craftsmen in Epirus, Western Macedonia, and the rest of Greece were informed that Iran was seeking craftsmen to participate in the continuation and completion of the Trans-Iranian Railway’s construction. This likely happened through Greek engineers working in Iran, such as G. Georgopoulos, and representatives of the Belgian construction company “Companie Belge de Chemins de Fer et d’ Enterprises.” The presence of the Swedish-Danish syndicate in Iran since 1930 may also have played a role. Nevertheless, the details of the agreement are unknown. The unemployed Epirote craftsmen would be paid very well. They were accustomed to traveling, even abroad, so Iran did not seem that distant to them. As always, they left their families behind, and communication would be through letters by post. Epirus and emigration are two interlinked words. There is a special category of Epirote songs, the so-called songs of emigration. We would recommend listening (available in various versions on YouTube) to the song “I forget and rejoice” (Alismono kai hairo).

On October 29, 1935, a group of 35–50 craftsmen gathered in Ioannina. Fifteen of them came from Pyrsogianni. E. Venetis lists all the names of those who went to Iran. Among them was 30-year-old Georgios Tzoulis with his 20-year-old wife Konstantina, and the 12-year-old (!) Orestis Tzimas, from Kerasovo (Agia Paraskevi) of Konitsa, who lived in Iran for several years, got married, and had 12 children. Two of them were born in Tehran (1956 and 1959). It appears that Tzimas later returned to Greece with his family. Along with the Epirotes, there was probably also the 25-year-old V. Partalis from Voio, Kozani.

According to the craftsmen’s accounts, without escort or guidance from the construction company, they departed (probably from Preveza) for Piraeus. There, they bought tickets from the “Karagiannis” travel agency. On October 31, 1935, they boarded the Romanian ship “Tatsia.” They traveled in the ship’s holds under terrible sanitary conditions. Finally, on November 4, 1935, they arrived in Beirut. Trucks from the construction company awaited them at the port. From Beirut, crossing the mountains of Lebanon, they reached Damascus the next day. There, they stayed for four days. They attended a service at a local Orthodox church and continued their journey by bus toward Baghdad, through the desert. The route was particularly dangerous due to gangs and bandits that plagued the area. Midway through the trip, they stopped to rest and then boarded a train to the Iraq-Iran border. Upon arrival, Iranian authorities conducted a thorough inspection.

In addition to the Epirotes, at the same time or a little earlier, other Greeks had been hired for the construction of the railway in Iran. They came from Western Macedonia, Thessaly (including the Jewish-origin civil engineer Leon Sabtai from Larisa and the foreman Eleftherios Iliadis from Nees Pagases, Magnesia), Euboea, Samos, and Italian-occupied Karpathos. Notably, among the Dodecanesians who worked in Iran was the Mayor of Olympos, Karpathos, Michail Chiotis. Lastly, miners (especially skilled in placing explosives in underground galleries) and builders also went to Iran. E. Venetis lists them by name. However, we do not know their places of origin.

The work and stay of the Greeks in Iran

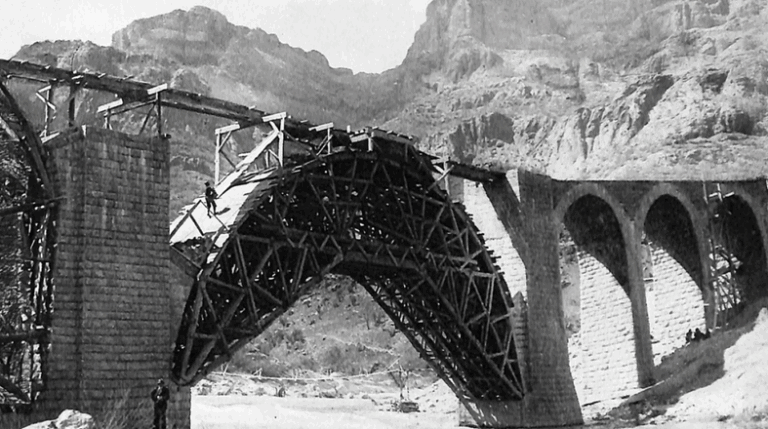

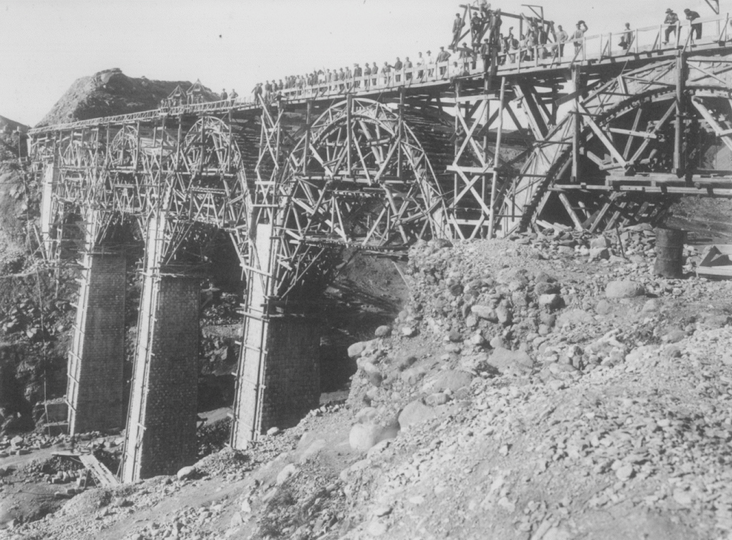

Unfortunately, not many details are known about the stay and work of the Greeks in Iran. Initially, they were transferred to Bijar, in Iranian Kurdistan, and were sent into the tunnels. The reason the Iranians invited the Greeks was their construction expertise using stone as a building material. The railway required craftsmen for the construction of bridges, both small and large, tunnels, etc., in mountainous or semi-mountainous regions where there was stone to be carved. Thus, the Greeks mainly worked in Northern and Central Iran. The holy city of Qom in Iran is also known for its stone, which is still quarried today from the neighboring mountain ranges. In nearby Gardaneh (120 km south of Tehran), it was decided to build a three-arched bridge to connect the elevations formed by the rocky desert. This bridge was a major project connecting Tehran and the city of Saveh in the north with Qom in the south.

The Greek craftsmen lived in makeshift accommodations. Gradually, they built their dormitories and other necessary buildings for their stay. In fact, in photographs of the time, one can see in the Epirote worksite stone structures built in their homeland’s traditional architectural style. There were also other workers living in shacks. The Greeks also worked in the Bavisi and Boroujerd regions.

Evangelos Venetis believes that the construction of the bridge in Gardane lasted at least six months. Along with the bridge, the Greek craftsmen built small and low supporting bridgeworks in the same area with the purpose of smoothing the relationship between the line and the ground. These bridgeworks are preserved to this day. Another location where the Greek craftsmen worked was the Mazandaran region of Northern Iran and the area of Shahrood. They posed a challenge due to their high altitude and rugged mountainous terrain. There, the Greeks collaborated with foreign colleagues and constructed bridges and tunnels in the areas of Veresk, Sari, and the surrounding locations. The bridges varied in span and had a height of 25–30 meters. The tunnels built by the craftsmen from Epirus are preserved in excellent condition to this day. They were built with stone on slopes 200 meters high from the ground. The stones were hewn with exceptional skill, and the joints between them reveal the special care and professionalism of the craftsmen. The Epirotes also went to the quarries but only to give instructions. The local people worked in them for very low wages.

In the construction of the Trans-Iranian Railway, the Greeks collaborated with Italians, Serbs, Bulgarians, Albanians, and others. Therefore, we do not know exactly how many projects they completed in Iran. Nevertheless, their contribution to the construction of this vast project was significant. Unfortunately, three Greek craftsmen—Vasilis Byrkos and Apostolis Papagiorgis from Pyrsogianni, and Xanthopoulos (no first name mentioned by E. Venetis)—lost their lives due to dysentery.

The…temptations for the Greeks in Iran – The return

The Greek craftsmen spent most of their time at the construction sites. Their dormitories were located nearby. They ate the rations provided by the company and did not cook as they used to in the work gangs. In the early days of their presence in Iran, they would often lose their way and until they became familiar with the area, they used to mark signs. They observed the celebration of important holidays, even Carnival. The westernized character of Reza Shah’s regime allowed them to drink alcoholic beverages, even though Iran is a Muslim country. The Iranians were hospitable and willingly helped the Greeks. Correspondence with their families was a problem for most since they were illiterate. The master craftsman and the few literate ones bore the burden of writing the letters. The daily wage of the craftsmen was 50–70 rials, a significant amount for the time. A large part of their earnings was sent to their families in Greece—usually collectively, in one envelope or sack for safety and practical reasons. The Epirotes met in Iran with other Greeks about whom we know little. The Greeks remained in Iran for nearly three years. The charming Iranian women were a temptation for the young Epirotes. Most… did not yield to the temptations. However, two Greeks, during the construction work in the Mazandaran province, met local women and married them. They stayed in Iran and settled in Tehran. In 1938, the Trans-Iranian Railway was completed. Following the reverse route from the one they had taken in 1935, they returned to Greece. There were some issues regarding the payment of the Epirote craftsmen. Eventually, they received a sum, smaller than the pre-agreed amount. The Belgian company paid them the remaining money upon their return to Greece.

The role of the Trans-Iranian Railway in World War II

The Greek craftsmen participated in the construction of a project with multiple significance—strategic and national in nature for Iran. The Trans-Iranian Railway marked, for the Asian country, the transition from the pre-industrial era to the modernization of its economy and society. Iran increased its geopolitical presence in the region and became an international transportation hub. The Trans-Iranian Railway played an important role in World War II. During the German operation “Barbarossa,” the Allies were able to channel ammunition from the Persian Gulf to the defending Soviet Union and influence the outcome of the war on the Eastern Front. Relevant bibliography: Robert W. Coakley, “The Persian Corridor as a Route for Aid to the USSR” in Greenfield, Kent Roberts, “Command Decisions.”

The “Museum of Epirote Craftsmen” plagued by state bureaucracy

In Pyrsogianni, one of the Mastorochoria (Craftsmen Villages) of Konitsa, a collection of material on the life and work of the craftsmen from the Mastorochoria of Konitsa and the broader mountainous region of Pindus began in 1976. This material was housed in the school of Pyrsogianni after it ceased operating (due to lack of students…). In 1999, the then Municipality of Mastorochoria submitted complete studies for its funding, aiming for the unique—in Greece—museum of Pyrsogianni to function as an exhibition and conference center. Unfortunately, this was not achieved. A new, comprehensive application for inclusion in the LEADER program of the LAG “EPIRUS S.A.” was submitted by the Municipality of Konitsa (which now included the Mastorochoria) in 2014 (Project Application File for the “MUSEUM OF EPIROTE CRAFTSMEN”). Although all the requirements were met, the political change in 2015 and the bureaucracy did not allow the inclusion of the “MUSEUM OF EPIROTE CRAFTSMEN” in LEADER. Unfortunately, it seems that for some officials, the prefecture of Ioannina does not include Konitsa and Pogoni. The Epirote craftsmen were worthy ambassadors of Greece in many parts of the world. Let the State finally take care to fulfill a minimal part of its debt to the remote regions of the prefecture of Ioannina. The funding and full operation of the “MUSEUM OF EPIROTE CRAFTSMEN,” at a time when others are throwing parties with state money, would be a good start…

Source: Evangelos Venetis, Hellenism in Modern Iran, with the contribution of Elli Antoniadou, Poreia Publications, 2010.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions