For centuries, the coffeehouse has been a social, political, and cultural hub that deeply influenced Greek society. The eminent writer (the “saint of letters”) and coffeehouse enthusiast Alexandros Papadiamantis traces the introduction of coffee into Greek lands back to the 1700s, although as early as the 17th century Thessaloniki already had countless coffeehouses and similar hangouts, especially in the Vardaris district. He himself enjoyed frequenting the Dexameni coffeehouse in Athens, as well as Forlidas’ coffeehouse in Pelion—the oldest in Greece, continuously operating since 1785.

With the end of the Revolution and the establishment of the Greek state, coffeehouses spread rapidly throughout the country. At the same time, the first urban coffeehouses appeared in Athens, the capital of the Greek state since 1834. “The Green Tree,” “Beautiful Hellas”—all were centers of discussion, political conspiracies and decisions, revolutionary proclamations, and places where anti-monarchist pamphlets could be found. They played a crucial role during the difficult years that followed.

Meanwhile, toward the late 1800s, the café-amán began to timidly appear. These were popular coffeehouses where singers improvised freely in verse, creating the famous amanés. The café-amán ceased to exist after Metaxas’ Presidential Decree of 1937, which banned amanés in public spaces.

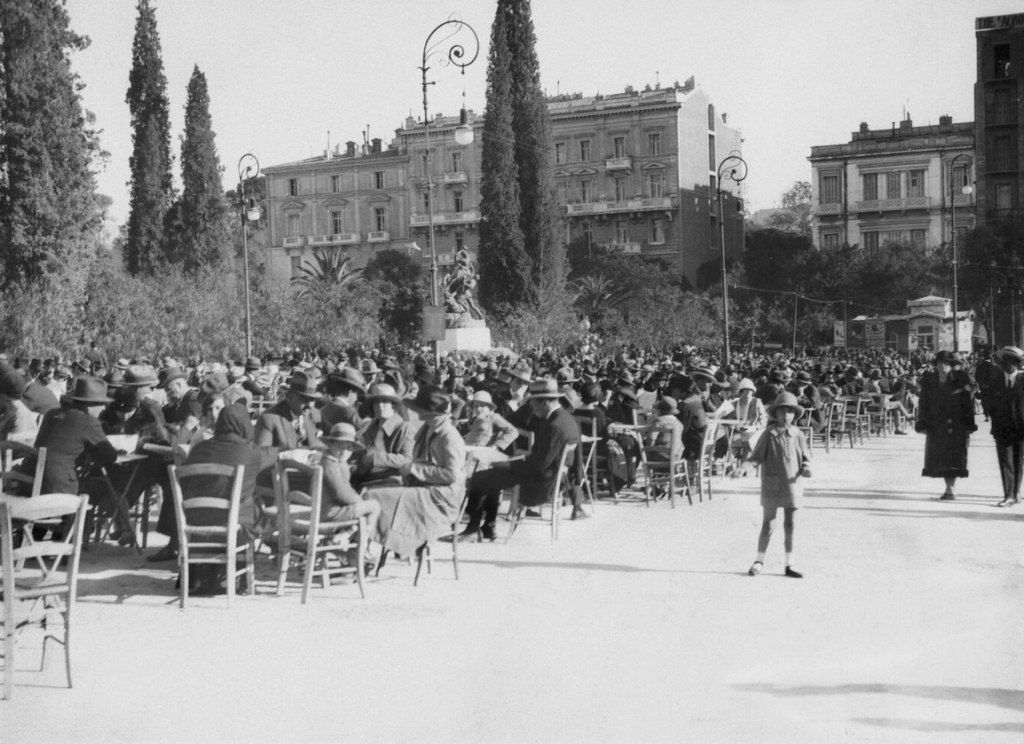

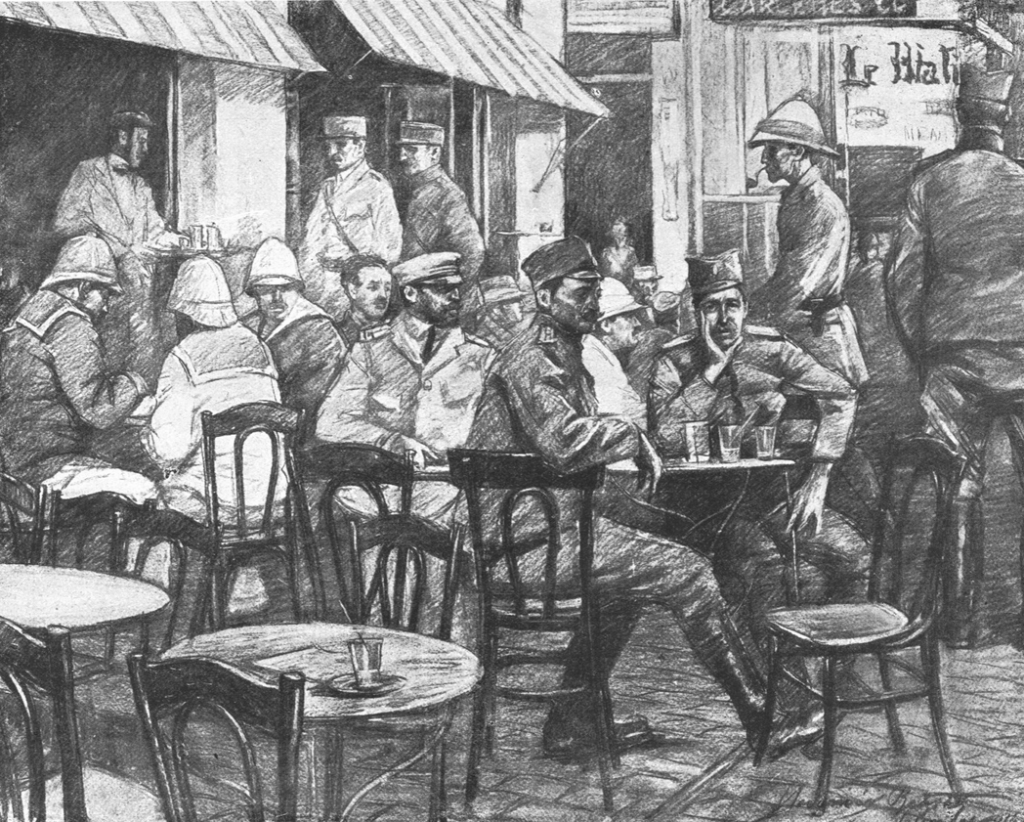

The turn of the century found Athens divided between the café-amán and their glamorous rivals, the café-chantant. French, Italian, and Viennese performers, along with entire troupes, offered dance, songs, and satirical theater improvisations. The audience consisted mostly of men, primarily from the middle and upper classes.

During the Interwar years, the Loumidis coffeehouse in Athens flourished as a central meeting place for intellectuals, writers, and poets, while the cosmopolitan “Café Doré” in Thessaloniki also stood out.

Then came the War years. Coffeehouses changed form, becoming centers of resistance under strict surveillance. Hunger, poverty, hardship, and above all the shortage of raw materials forced people to seek substitutes for coffee. I remember my grandfather telling me about ground chickpeas they drank during that period.

In the years following the War, a new generation of coffeehouses appeared. Names like “Roumeli” and “Epirus” reflected the internal migration that followed the Civil War and reshaped the social fabric of Athens. At the same time, the arrival of black-and-white television in coffeehouses created the phenomenon of collective viewing—not only of football matches, but also of political developments and world events.

It was the era when taverns created a demand for dining out. Yet they also held a crucial political role, as members of parliament began choosing coffeehouses across the country for their major speeches. In post-junta Greece, a new type of recreational space with a similar social character was introduced: the café. For many, it was the evolution of the traditional coffeehouse; for others, not.

Identity

Through time, coffeehouses have always been spaces with a strong social, and above all, human identity. Scattered, isolated coffeehouses across Greece were for years the only links to the outside world. Here, the postman would arrive once a week, or even less frequently, to deliver correspondence—a precious gift for generations and the sole channel of contact with loved ones.

Here, retirees would wait for their pensions, using them to make essential purchases after carefully counting the money in their hands. And the coffeehouse owner, acting like a kind of ambassador of social responsibility, safeguarded letters and pensions like priceless talismans until they reached their recipients. Outdoor vendors of all kinds would always stop outside coffeehouse doors to announce their wares.

The coffeehouse was and remains the meeting place and reference point of every village in the Greek countryside. Alongside its social significance, it has historically been an important hub for communication and entertainment. Telephones, radios, and black-and-white televisions first appeared in coffeehouses. The shadow theater of Karagiozis first entered villagers’ lives through them.

Traveling troupes would set up projection screens and invite the village to watch the early cinema of the time. Across generations, coffeehouses were spaces where men of local communities spent a significant portion of their time over a Greek coffee, a bottle of retsina, or a beer. They were meeting places, venues for commercial transactions, spaces for debate and political confrontation, centers for information, and forums for exchanging opinions on professional matters.

They were places of supply and demand, as well as joy and celebration. They were also spaces for games. And when the coffeehouse briefly closed its doors—just long enough for the owner to rest—it was as if time itself paused. As if life’s clock interrupted its endless flow. As if it rested, together with the stories and passions of the countless people it had hosted.

Coffeehouse vs. Café

It is essential that our coffeehouses remain the living social pillars they have always been—“the small parliaments of the country,” as Giorgos Pittas aptly notes.

Speaking with him over coffee one afternoon in a traditional Athens coffeehouse, I realized the deep love of a man who has traveled, and continues to travel, across the country to map and study our traditional coffeehouses. When I asked him whether today’s café is the evolution of yesterday’s coffeehouse, he replied:

“In the coffeehouse, the past is present. History gives prestige to the space. Today’s café cannot be the evolution of the coffeehouse for a simple reason: the pressing need for renovation prevents any trace of history from forming in the space.

Traditional coffeehouses will continue to exist as long as the grandchildren of the old owners wish to carry on the coffeehouse profession. They just need to understand that being a coffeehouse owner is by no means a demeaning profession. On the contrary.”

The 8 Rules

– We don’t go to the coffeehouse for a meal. The coffeehouse meze (small appetizers) whet the appetite before eating.

– At the coffeehouse, we don’t reciprocate a treat for the one who treated us.

– When treating someone, we don’t pay immediately; the bill is settled at the end.

– Unlike in a tavern, order and organization prevail in the coffeehouse.

– We don’t get drunk in the coffeehouse; sobriety is the norm.

– The coffeehouse fosters a sense of sharing.

– In the coffeehouse, the old is also new. The charm of the patina of time is a defining feature.

– Things have always been lighter in the coffeehouse. In the tavern, the deeper instincts of our existence emerge.

Childhood Memories…from a Centuries-Old Coffeehouse-Grocery in Rachi, Ithaca

I still remember my childhood in Ithaca, at Apostolaris’ coffeehouse in Rachi, where the heartbeat of the entire village could be felt. My godfather, Grigoris, the church warden of Evangelistria, held my hand tightly and always treated me to an orange soda and those amazing little loukoumades—the bite-sized sweets that the tall, lanky owner of the coffeehouse, known as Kostopoulos, took out of a large paper box.

“I bring them from Patras; they are the best loukoumades. Do you know how much they cost me?” he proudly said as he unwrapped the thin paper around each bite.

On the worm-eaten wooden floor, two small tables and a few wicker chairs created the necessary scene for this peculiar prose. A theater of toil, starring the everyday heroes of a place that was both wild and paradisiacal, on the slopes of Kioni Bay in northern Ithaca.

Everyone had their own sweet eccentricity. Everything sparked debates—from their folk wisdom and kindness to their knowledge and cunning. The vineyards, the fields, the weather, village news, news brought by Ithacans from the rest of Greece, football, and politics.

Above all, politics. That’s where the biggest disputes happened. As if all the toil of hard daily work found fertile ground to erupt over predictions about the country’s economy or foreign policy. On the parchment paper: corned beef, ham, canned sardines with hot red pepper, a salad-paste, octopus, real bread on wooden boards, or rusk when there was no bread, olives, tomatoes, and cheeses from the island’s local producer.

In the basement of the century-old stone building were the wine press and linen, wine barrels, and all the necessary tools for vineyard work. Kostopoulos was very proud of his own wine.

This was my village’s coffeehouse—a living memory of a bygone era, leaving behind indelible marks.

As Giorgos Pittas, Greece’s foremost scholar on coffeehouses and author of The Coffeehouses of Greece, recently told me: “Coffeehouses are the small parliaments of villages. The coffeehouse is the man’s leisure. The coffeehouse is, and will continue to be, an existential necessity for the Greek.”

Legendary and Modern Coffeehouses

Within the climate of Greek identity we experience today, coffeehouses are returning in modern forms, attracting younger generations.

Coffeehouses in Greece were always more than just places for coffee or tsipouro. They were gathering points, places for conversation and relaxation after work. Today, the scene has changed radically. New coffeehouses are thriving, attracting a different, younger audience, more open to flavors.

“People need something simpler and purer. They want good ingredients without fuss, and dishes where you can recognize what you’re eating,” explains Aris Sklavenitis, co-owner of ¡Topa!. The main difference is the kitchen. “There’s more careful selection of products; people want to try new things.” Yet the essence remains the same: the coffeehouse is still a meeting place—only now with more flavors, more options, and a sense that tradition can become relevant again.

Iconic Coffeehouses

Kafetheatro 1929 / Amfissa – The legendary Panellinion, where a scene from Theodoros Angelopoulos’ The Beehive (1976) was filmed.

Forlida Coffeehouse / Pelion – Where Papadiamantis drank his wine.

Kostas’ Coffeehouse / Siva, Crete – A mystical coffeehouse filled with icons and photos of works by El Greco.

Kyra-Rini’s Coffeehouse / Lesbos – Known for exceptional spoon sweets from Kyra-Rini’s granddaughter.

Skoulas’ Coffeehouse / Anogeia – In the famed village of Crete on Psiloritis, where time stops and bows.

Sarantavgá Coffeehouse / Heraklion – An urban coffeehouse, over a century old, with the charming patina of time on its walls.

Kyma Coffeehouse / Donousa – A coffeehouse-grocery-kitchen, an integral part of the island.

Chara Coffeehouse / Schinoussa – A local and tourist favorite, known for excellent sweets.

The Great Coffeehouse / Tinos – Traditional since 1920, in the village square of Pyrgos with its large plane tree.

The Great Coffeehouse (Athanasiasdeion) / Plomari – A grand coffeehouse in Lesbos, built in 1902, donated by the Greek teacher Ionas Athanasiadis.

5 Historic Coffeehouses in Athens

“Beautiful Hellas” / Monastiraki – Traditional coffee on embers, on Mitropoleos Street, for over 50 years.

“Mouria” / Exarchia – Since 1915, a meeting place for all generations, regularly interacting at its tables.

“Panellinion” / Exarchia – The chess coffeehouse of the city center, which hosted world chess champion Karpov for simultaneous play on 30 boards.

“Ikariotiko” / Piraeus Port – Serving meze and sharing fascinating sailor stories since 1956.

“Lesvion Ouzeri Coffeehouse” / Galatsi – A decades-old hangout, evolving since 1965 from a classic coffeehouse to a gastronomic destination.

5 New Coffeehouses in Athens

“Afea” / Thiseio – A modern, sunny coffeehouse for beer, ouzo, tsipouro, and wine with selected dishes.

“Allios” / Kypseli – Paying close attention to the origin of every drink served, with regularly updated handmade meze.

“¡Topa!” / Kypseli – The Cretan-Basque coffeehouse on Fokionos, serving delicious Cretan and Basque small dishes, with special attention to vermouth.

“To Louvron” / Pangrati – Creative recipes and aged tsipouro in this Pangrati hangout.

“Dexameni” / Kolonaki – High in Kolonaki, serving freshly brewed coffee and meze from morning till night under the trees of the pedestrian street.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions