In the world of fashion, where image is currency and storytelling is strategy, Olivier Rousteing decided to do something radically different: be real. The former head designer of Balmain, the man who put hashtags in the DNA of Parisian luxury, created his own “Balmain army”, a group of celebrities such as Kim Kardashian, Gigi Hadid, and Kendall Jenner, who, through social media, helped shape the brand’s new image.

They have also contributed to the creation of the new image of the brand.

End of an era for Balmain

After fourteen years at the helm, Olivier Rousteing announced yesterday that he was leaving the historic house, closing a chapter that defined modern French fashion. In a statement, the house expressed “deep gratitude for his significant contribution to the history of the house”, adding that “a new creative structure will be announced in due course”.

Rousteing himself confirmed his departure via a personal Instagram post: ‘Today marks the end of my time at Balmain. Sixteen years ago, I started this adventure without knowing what the future would bring. What an incredible story! A love story, a story of a lifetime.”

In the same message, he thanked his colleagues, the family he chose, and the Mayhoola Group for their support, “I arrived at 24 with eyes wide open and the determination to persevere. Today I leave with eyes just as wide open, open to the future and the beautiful adventures to come.” His departure, as confirmed by the house, was “by mutual agreement”.

Rousteing, born in 1985, was adopted by a French family in Bordeaux and grew up knowing nothing about his biological parents, an affair that followed him into his thirties. When, at the age of 24, he was appointed artistic director of Balmain, he became the youngest designer to hold the most senior position at a French house since Yves Saint Laurent.

Rousteing studied at ESMOD in Paris before joining Roberto Cavalli, where he eventually headed the womenswear department. He joined Balmain in 2009, under the direction of Christophe Decarnin, whom he succeeded two years later, even surpassing Alber Elbaz’s 14-year tenure at Lanvin. He approached it with a dose of humour and thoughtfulness: “When I started, I was the new kid. Now, I’m the last one left,” he has said.

The glamour of Balmain in the Rousteing era

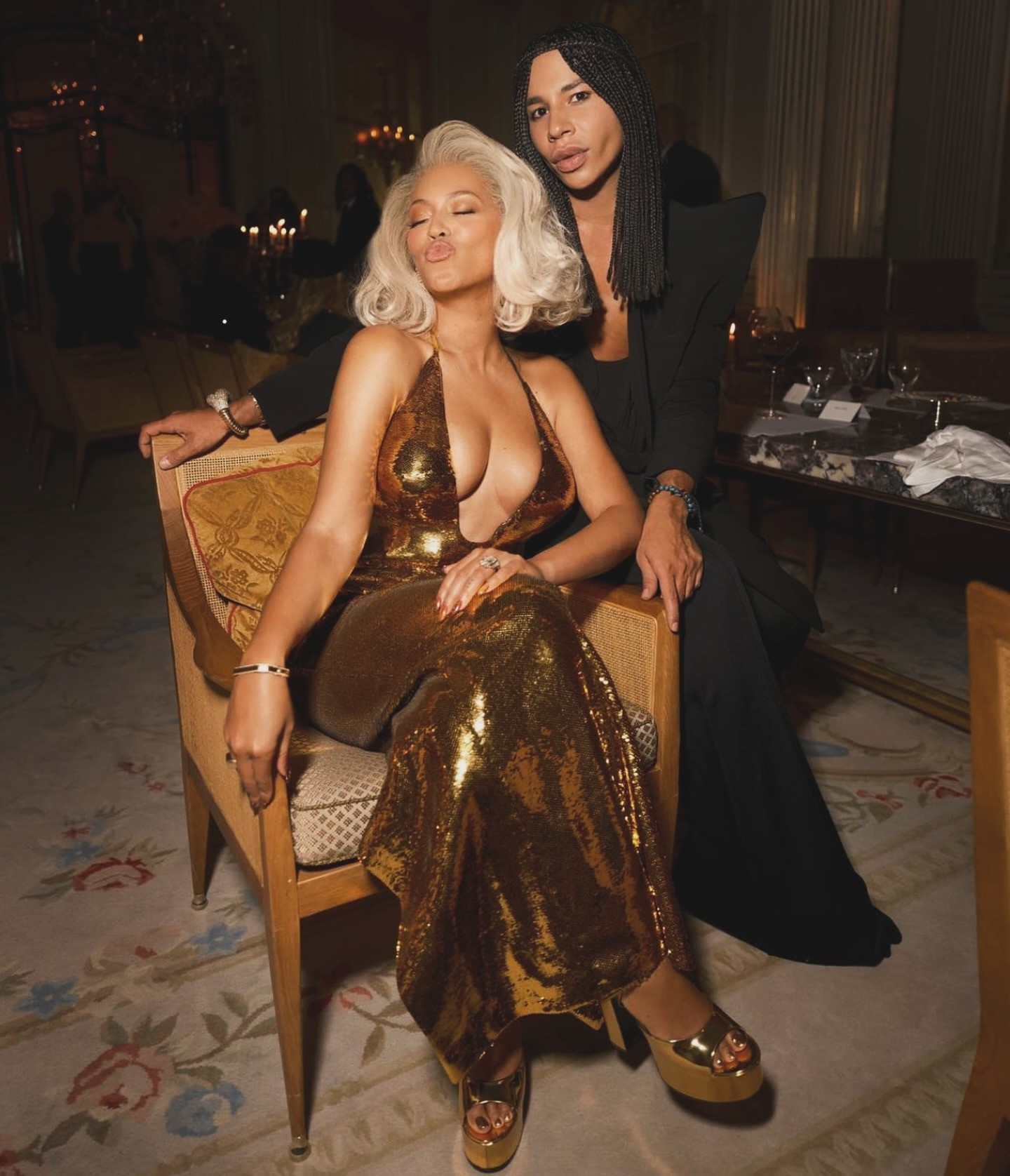

Under Rousteing’s direction, Balmain became a global symbol of dynamic luxury, identified with power dressing, dazzling embroidered crystals, and sculptural silhouettes worn by Beyoncé, Rihanna, and Kim Kardashian, among many others. His influence has long since transcended the boundaries of fashion: he revived Balmain’s haute couture line after a 16-year hiatus, has designed costumes for the Paris Opera, and has collaborated with some of the most influential names in contemporary pop culture. At the same time, he became the “digital” representative of a new generation: his Instagram, with millions of followers, was and still is a showcase of success, celebrity friends, and perfect selfies. Only behind the flashes, there was a void. “I had become a caricature of myself,” he admits in the documentary Wonder Boy, by Anissa Bonnefont. “My image was my defense.” So when Bonnefont asked him if he wanted to look up his biological parents, he said yes.

Wonder Boy is not the expected fashion documentary. Although we see Rousteing in his atelier overseeing fittings, directing his team, and walking with an air of stardom at the finale of the shows, the camera follows him not as an idol but as a man. It follows him in his Paris apartment, eating cereal alone at the big table, visiting his foster grandparents in Bordeaux, and moving in front of a psychologist as his adoption file opens.

The revelation is painful. He learns that his mother was Somali, only 15 when he was born, and his father was from Ethiopia. “I always thought I was mixed race. But I am black. I’m African-American,” he says. The moment is shocking not only for him, but for anyone who understands how deep the question of identity can run, especially in a country like France, where, as Bonnefont says, “who you are is determined by where you come from.”

Rousteing did not ask for pity. On the contrary: he wanted to prove that “you can have the dream without being perfect.” Using the power of the image he once used as armor, he now attempts to give voice to a generation struggling to understand itself. His personal story is linked to the wider issue of diversity in French society, to the silences surrounding adoption, to the need to redefine what success means.

Balmain’s chief executive, Massimo Piombini, put it simply: “This guy, a child of two different cultures, gay and an orphan, didn’t start from scratch. He started at minus ten.” And yet, within a decade, Rousteing managed to resurrect Balmain, attract a new audience, connect fashion to mass culture and become a face of the modern age.

The quiet side of success

The price, of course, is loneliness. “Fashion gave me the dream, but there is always a price,” the designer says. “You trust people less. And when your first love, your mother, has abandoned you, it’s hard.” Rousteing’s story doesn’t have a happy ending. Although social services tracked down his mother, they were unable to reveal her name. They suggested that he write her a letter so that she could decide if she wanted to meet him. He still hesitates. As he has stated in later interviews, there was never any communication between them, as he preferred to respect her silence and focus on his own journey of self-discovery.

Olivier Rousteing leaves Balmain, leaving behind an era of brilliant creativity and extroversion. At the same time, he seems to be leaving behind the facade that protected him, accepting himself with a new, quiet certainty. A return to a more human, authentic version of himself. Perhaps this is true freedom: not reinvention, but reconciliation; to be able to face the world without filters, simply as you are.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions