The answer is not easy. Yet when the leaders of the two Churches converge and communicate, new paths open; obstacles diminish and resistance subsides. Indeed, just before the millennium anniversary of the 1054 Schism, expectations that Christianity is entering a new era are gaining substance and perspective.

But the journey will be long and arduous. It took nine whole centuries before, in 1965, Patriarch Athenagoras and Pope Paul VI jointly lifted the mutual anathemas of 1054. Since then, even with small steps, relations have steadily improved, and new prospects continue to expand.

In recent years, under Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew at the Phanar and Pope Francis in the Holy See until his passing, developments were spectacular. To the point where both sides openly discuss establishing a common Easter date — an idea that, despite its challenges, now seems mature enough to be placed on track.

At the Phanar and in Nicaea

Within this context, the upcoming visit of the new Pope Leo XIV to the Phanar next Saturday, November 29, is of exceptional interest. After the doxology in the Patriarchal Church of St. George, a joint declaration will be signed by the leaders of the Orthodox and Roman Catholic Churches.

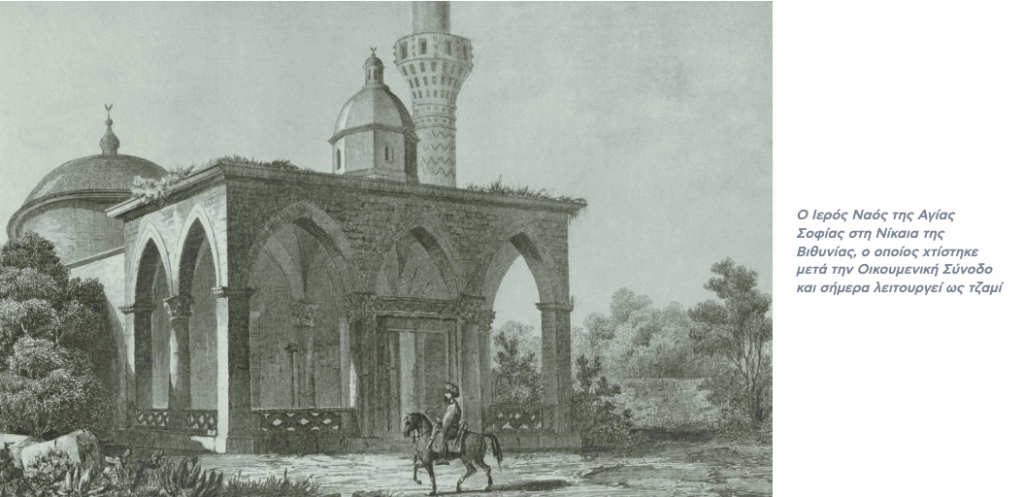

Equally symbolic is their joint visit one day earlier to Nicaea (modern-day Iznik), where they will hold an ecumenical prayer marking 1,700 years since the historic First Ecumenical Council.

The Council answered major theological questions of Christianity and, by formulating 20 canons, set the doctrinal and canonical foundations of the Church. There, the early Fathers defined fundamental doctrines: the date of Easter, the explanation of the Trinity, and the affirmation of the divinity of Jesus. They agreed that Jesus was “God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten, not made, consubstantial with the Father,” as stated in the Nicene Creed (“Pistevo”), considered a foundational declaration of Christian faith.

For more than seven centuries, the new faith moved with unity before division and rupture occurred. That is why the powerful symbolism of the joint visit of the Patriarch and Pope to the meeting place of the 318 Bishops of the Council — the imperial palace of Emperor Constantine the Great, now in ruins — reflects new realities and rekindles hope for unity.

How the two leaders frame this new prospect

Patriarch Bartholomew recently declared during the Divine Liturgy at the Dormition of the Theotokos Church in Valinos:

“Today we believe we can no longer live in isolation, with self-sufficiency and self-complacency, but that we need each other. We have a collective responsibility for a common Christian witness in the modern world, for whose peace we pray daily and to which we preach love as the highest ideal. How can we be persuasive and credible if we are not at peace with one another and do not love one another?”

Months earlier, the Ecumenical Patriarchate emphasized in an official Encyclical that:

“Since the canonical legacy of Nicaea is a shared inheritance of the entire Christian world, this anniversary must serve as a call to return to the sources, to the primordial message of the undivided Church.”

On the other side, Pope Leo XIV has delivered his own message:

“The Council of Nicaea is not merely an event of the past but a compass that must continue to guide us toward full visible unity among all Christians.”

Ask me anything

Explore related questions