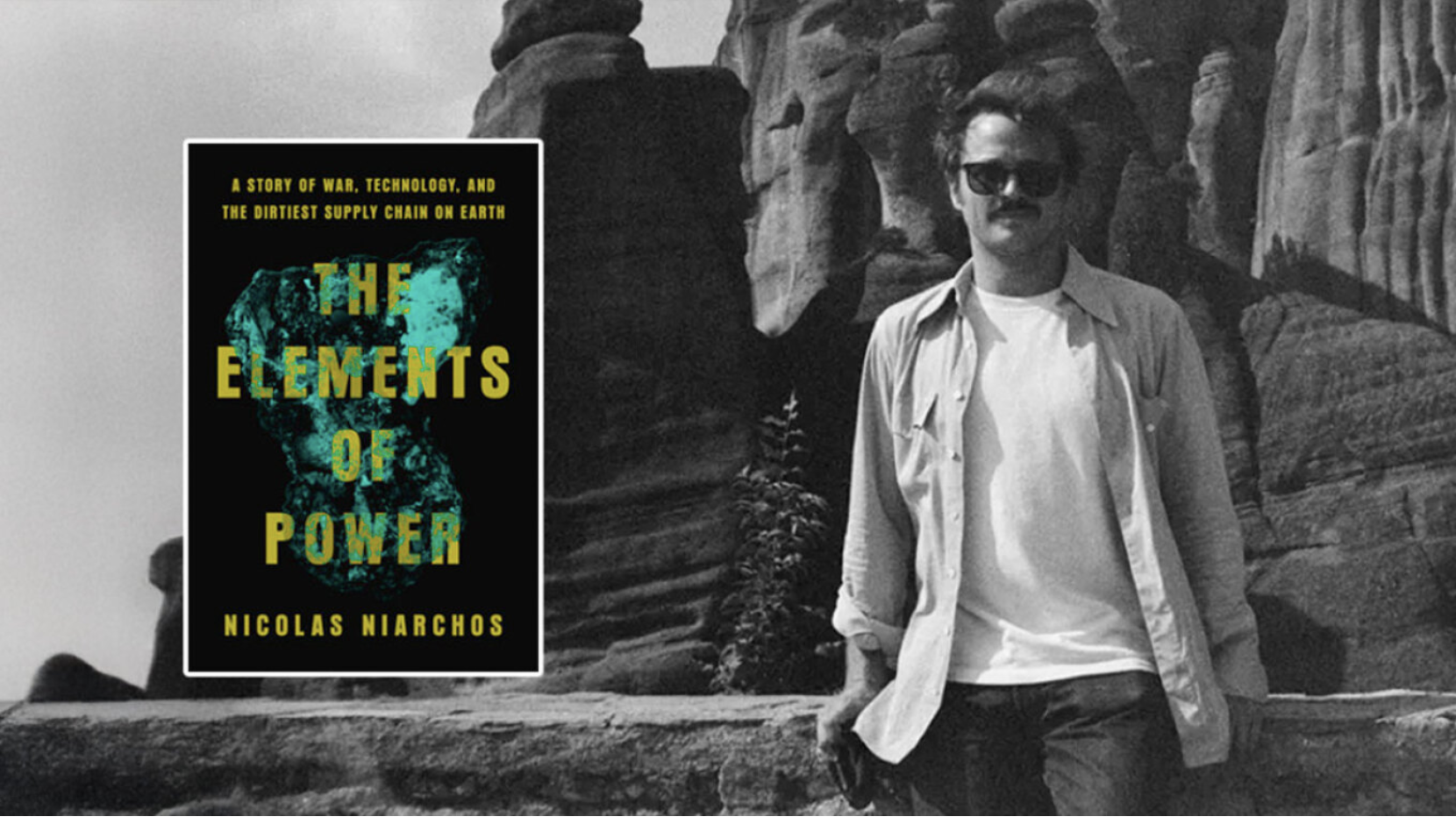

The journalist and son of Spyros Niarchos is set to release a book in a few weeks titled The Elements of Power, based on his years-long investigative journalism into the global “war” over metals for lithium-ion batteries.

Tracing their journey and mapping the supply chain for their production, 35-year-old heir Nicholas Niarchos tells the story both of the people driving this race and of those whose lives are dramatically upended.

Last Tuesday, in an Instagram story on his personal account, Niarchos tenderly kissed his wife Malou, whose birthday it was.

They celebrated a few weeks before the release of the first book authored by the 36-year-old son of Spyros Niarchos, who chose the path of journalism—an unusual choice for an heir to such a powerful dynasty.

The book, titled The Elements of Power, delves into the depths of a commercial war raging over the global supply of metals used in lithium-ion batteries.

It vividly portrays the stories of the people at the forefront of this industry, as well as those working for less than a dollar a day in cobalt mines in the Congo, under inhumane conditions.

Niarchos visited the country multiple times in recent years, among others, and was eventually arrested, detained, and deported as a persona non grata because of his reporting.

So far, the Congolese government has not returned the phones and computer of this persistent journalist, who relentlessly pursues stories in Europe, Africa, and the war in Ukraine, publishing in The New York Times and The New Yorker.

The Arrest in Congo

“Congo is rich,” Niarchos writes in a small excerpt from his book made public. “Vast areas of the war-torn African country lack basic infrastructure, and after many decades of colonial rule, its people are officially among the poorest in the world.

But beneath its soil lie enormous quantities of cobalt, lithium, copper, tin, tantalum, tungsten, and other treasures. Recently, this real-life periodic table of resources has become extremely valuable, as these metals are essential for the global ‘energy transition’ envisioned by rich nations seeking to move away from fossil fuels to sustainable energy forms like solar and wind.

In this push for green energy, the world has become utterly dependent on resources discovered far away, often blind to the devastating political, environmental, and social consequences of their extraction.

If the Democratic Republic of the Congo is so wealthy, why do its children consistently descend into dangerous mines to dig with rudimentary tools—or, in some cases, with their bare hands? Why is Western Sahara, a source of phosphate, still treated like a colony? Who should pay the price for progress?”

The questions Niarchos raises stem from his careful investigative work, which brought him to the Democratic Republic of the Congo in July 2022.

He sought to examine working conditions in cobalt mines, where even children labored exhausting hours for less than a dollar a day.

When he contacted rebels without informing the government, the then-33-year-old freelance journalist was arrested by the ANR, the country’s Central Intelligence Agency.

“The experience of detention is soul-destroying,” he told The New York Review, adding, “I felt awful every day for my family and the families of those detained with me… They had no idea where we were for days and were frantic with fear and anxiety.”

A grim prison cell is hardly where you would expect to find a Niarchos, who vividly described his experience in captivity.

“Conditions in detention were harsh. There was very little food—I ate properly only once in six days—and fortunately, I had some sardines and cereal in my bag, while our personal belongings were gradually stolen.”

He was eventually deported, and, as he said, “The whole experience made me more careful in my work, as it turned out one of my sources was involved in a government plot to trap me.”

To complete The Elements of Power, he spoke again with his sources in the Congo from afar, as the government does not allow him back into the country.

From Mytilene to the Sahara

Before Congo, Spyros Niarchos’ son had traveled to various countries for reporting, even while on vacation.

“In 2015, while I was a fact-checker at The New Yorker, I visited my family in Greece when the refugee crisis erupted in Europe,” he said in the same interview with The New York Review.

“I soon flew to Lesbos to witness a human sea arriving from Syria and Iraq, fleeing ISIS. I began covering refugee crises wherever I could, even during vacations, to report from Djibouti and Western Sahara. I suppose my desire to work in Africa started there.”

Thirty-six years after the day he first cried when he was born, Nicholas Niarchos is not only a successful freelance journalist.

He is a rather uncompromising heir, writing for the left-leaning The Nation and criticizing Trump with ease, while traveling to Yemen for the next story for The New Yorker.

In the streets of Harlem in New York City, where he has lived permanently with his wife Malou for years, few recognize him as a famous heir to the Niarchos dynasty.

Most see a reserved young man with thick-rimmed glasses who never used his influential surname, which opens many doors, especially in his line of work.

He grew up in a privileged environment, with his mother Daphne Guinness always by his side and his father Spyros Niarchos, though he witnessed his parents’ divorce at age ten. Even as a student at a prestigious private school, he discovered a passion for journalism and knew from adolescence that he wanted to pursue it professionally.

Baptism by Fire and Ukraine

When accepted to Yale University, he studied literature and politics, then completed a master’s in journalism at Columbia.

His busy father, Spyros Niarchos, did not object to his son entering a field where a powerful name usually holds little sway.

As a student, he wrote for the university newspaper, Yale Daily News, and hosted shows on the campus radio station.

After graduating, he focused on investigative journalism, knowing he would not frequent the places his cousins Stavros and Eugenia Niarchos did, but instead venture into countries torn by civil wars and conflicts.

He speaks five languages fluently, including Russian and Italian, and developed a distinctive personal style from the start of his career.

He grew up moving between the U.S. and the U.K., writing his early pieces in London while collaborating with The Guardian, and later with The Independent and The Observer.

The refugee crisis in 2015 was essentially his baptism by fire, after which he went to Burkina Faso, Yemen, and almost immediately to Ukraine when the war broke out.

In a recent Instagram story, Nicholas Niarchos tenderly kissed his wife Malou on her birthday.

He has reported stories published primarily in the left-leaning The Nation, The New Yorker, The New York Times, and The Guardian.

He has traveled extensively in Greece with his siblings or alone, visiting islands like Kasos, Skyros, and Velopoula, a small islet between Spetses and Milos, which he photographed with the camera that almost always hangs around his neck.

Last summer, he married his long-time partner Malou in a ceremony on Spetsopoula, attended by the entire Niarchos family and about a hundred guests.

The wedding stayed private, as neither his siblings nor cousins shared stories on social media, except for a single photo showing the couple with their backs to the camera.

Following the honeymoon, Nicholas Niarchos returned to the work that drives him, preparing for his next major report.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions