“Walk faster, or we’ll miss the last trolley,” a nostalgic twist on an old tune might go—an ironic lyric, considering that trolleybuses arrived in the 1950s to replace the tram system. The tram rails were torn up to make room for trolley lines, which are now themselves being dismantled to make way for next-generation electric buses.

Transport Minister Konstantinos Kyranakis has approved the gradual retirement of trolleybuses, calling them outdated in an era of wireless electric mobility—technology that renders the old cable-dependent system expensive to maintain and limited in flexibility.

Supporters say the change will “open up the Athenian skyline” and reduce traffic congestion caused by frequent breakdowns. Critics, however, argue that trolleybuses are still one of the most energy-efficient, sustainable and cost-effective forms of public transport—and that they don’t require charging. Some even ask that at least one or two lines remain for nostalgia’s sake, though this idea appears unlikely to be adopted.

Nearing the End of the Line

By 2027, trolleybuses are expected to disappear entirely after a two-phase withdrawal:

- The dismantling of overhead wiring in central Athens—already underway.

- Complete removal of the vehicles from service.

Soon, the familiar whir of the electric motor, the whistle of the pantograph sliding on the wires, and the sight of the yellow (or, recently, blue) trolley gliding almost silently through Athens’ avenues will exist only in memory.

After 72 consecutive years, one of the capital’s most characteristic transport systems—beloved by some, disliked by others—is reaching its terminus.

The First Trolleybuses: Green, Italian, and Almost Forgotten

Greece’s first trolleybus ran in 1948 between Piraeus and Kastella—a Fiat model that survives today as a historic relic.

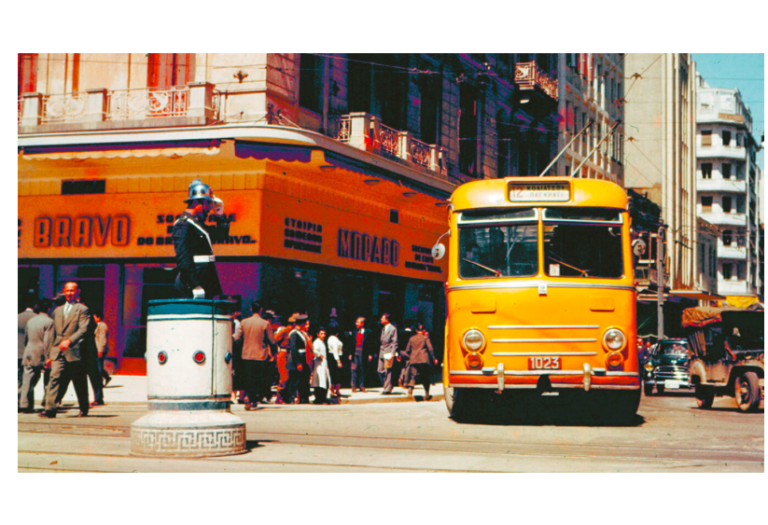

Back then, trolleybuses arrived painted green from the factory. Only after the war did the operating company repaint them yellow-orange, so they would match the city’s trams and buses.

The first Athenian trolley route opened on 27 December 1953, replacing the tram line between Patissia and Ampelokipoi. Many Athenians were slow to accept them, continuing to call them “trams” and referring to drivers as “trambagerides” long after the tram system was gone.

Smoking was banned on board—a rule printed on signs that many found impossible to obey at the time.

A Fleet of Legends: Fiat, Alfa Romeo, Lancia

Athens today has around 210 trolleybuses serving 19 routes, though many are over 20 years old. Earlier generations included:

- Fiat, Alfa Romeo, and Lancia models from the 1950s–80s

- Soviet-built Energoma Chexport vehicles (1972–1992)

- Later additions from Neoplan, Van Hool, and Solaris

Trolleybuses traditionally run on 600V DC, fed continuously from overhead wires through dual pantographs. Unlike battery buses, they carry no heavy battery packs—making them lighter and more efficient, but completely dependent on the grid.

Every Athenian has seen the iconic image of a driver stepping out with a long pole to reconnect a pantograph that popped off the wire.

The Rise and Fall of the Trolley Era

In 1970, management shifted to the newly created ΗΛΠΑΠ (Electric Buses of Athens–Piraeus), which expanded the network through the 70s and 80s. But in recent decades, the system suffered:

- declining reliability

- lack of parts

- financial crisis

- poor maintenance

The once-impressive 91% reliability rate has plummeted.

The most iconic trolley of all is the “Falkonera”, a unique Greek-built prototype presented in 1967 at the Thessaloniki International Fair. It served on the Kypseli–Kaisariani route and even played a role during the Athens Polytechnic uprising, where it was used as a makeshift barricade on Patission Street. Today, it rusts away in the OSY depot in Ano Liosia.

From Pollution Crisis to Obsolescence

In 1984, when Athens choked under smog, authorities sought to expand the trolley network, even attempting (unsuccessfully) to convert gasoline buses into trolleybuses.

Yet now, the same system is considered outdated.

Passenger usage has dropped sharply:

- Routes reduced by 28.7% between 2016–2021

- Active vehicles decreased from 286 (2021) to 209 (2024)

A study by NTUA shows that maintaining new electric buses costs 40–50% less than maintaining aging trolleybuses.

Electric Buses Without Wires: The Future Arrives

Supporters of trolley preservation point to modern “In-Motion Charging” trolleybuses—vehicles that can charge while moving under wires and then continue wire-free. These systems are cheaper and longer-lasting than battery buses.

The government counters that the newest electric bus models offer exceptional autonomy and eliminate the need for costly overhead infrastructure. The cable network consumes power even when no trolleys run and requires expensive substations, while also restricting routes.

Some fear that replacing the long articulated trolleys (“accordion” buses) with smaller vehicles will worsen crowding, though this has not been confirmed.

A Final Wish: Keep at Least One Alive

There is talk—though no official decision—of preserving at least one trolleybus as a mobile museum exhibit, possibly in cooperation with the Hellenic Bus Museum.

And so, the old joke gains new meaning:

“Walk quickly—let’s catch the last trolleybus.”

Because soon, the last one really will be gone.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions