The retirement of the antiquated Predator drone MQ-1, which is to be withdrawn from service in July and replaced by the more capable MQ-9 Reaper, is giving military analysts an opportunity to review the mixed history of a weapon that has long been associated with low-cost war, a sense of disembodiment from conflict, and for inflicting a high number of civilian casualties.

“There’s a perception in large parts of the American political system that drone campaigns are more or less free, but that’s not true,” says Stephen Biddle, senior fellow for defense policy at the Council on Foreign Relations. “Like anything that’s perceived as free, it tends to get overused.”

The General Atomics remote-piloted plane entered service in 1995 as the reconnaissance drone RQ-1. But in 1999 it was fitted with Hellfire missiles and re-designated MQ-1, an ad-hoc adaptation that would give it a reputation as a silent assassin.

The first Predator strike is believed to have taken place in Afghanistan in 2002, but it was not until 2004 that the US launched its first drone strike in Pakistan, an attack that killed Taliban leader Nek Muhammad.

That set the pattern for hundreds of missions to follow, and a post-9/11 era of targeted killings, most shrouded in secrecy, in theaters of conflict including Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen, Libya, Syria, and Somalia.

According to the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, there were a total of 563 strikes, largely by drones, in Pakistan, Somalia and Yemen during Barack Obama’s two terms, compared with 57 strikes under George W Bush. The BIJ study estimated between 384 and 807 civilians were killed.

According to analysis by Micah Zenko of the Council on Foreign Relations, Donald Trump is currently on track to outpace Obama in terms of drone strikes. From his inauguration through 2 March, Trump approved at least 36 drone strikes or raids in 45 days – one every 1.25 days, Zenko calculates. By contrast, Zenko calculates that Obama approved one every 5.4 days.

Trump’s strikes included three drone attacks in Yemen on 20, 21 and 22 January; the 28 January Navy Seal raid in Yemen; one reported strike in Pakistan on 1 March; more than 30 strikes in Yemen on 2 and 3 March; and at least one more on 6 March.

The Trump administration has yet to enunciate its policy on drones. Alyssa Sims at the New America Foundation says that while the Bush administration pursued a policy of “personality strikes”, or going after known targets, the Obama administration took that a step further, pursuing a policy of “signature strikes”, or targeting based on behaviors or characteristics associated with terrorist activity.

That change in policy contributed to a significant increase in the number of civilians killed, Sims says. “There’s been a real lack of clarity [in terms] of who falls in the category of a terrorist signature – it’s never been explained, and the criteria never clearly established.”

But the record of drone warfare is mixed at best, says CFR’s Biddle. “They may suppress insurgent or terrorist groups, but only under special conditions do they ever actually defeat a group,” he says.

Those conditions, he says, include an immature terrorist movement that is highly dependent on a handful of charismatic leaders, circumstances neither al-Qaida nor Isis, both considered institutionalized and mature, meet.

“The harder they make themselves to hit necessarily involves killing a larger number of civilians, and that in turn increases the group’s recruiting potential,” Biddle says. “So what you tend to get is a stalemate. At a certain point, the negative political effect from killing innocent civilians starts to outstrip its military utility in suppressing the target.”

But that has not diminished the popularity of drones to military planners.

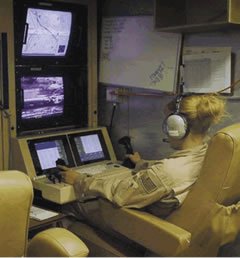

The US air force now has more jobs for drone operators than any other type of pilot position, the service said last week. With about 1,000 pilot operators, drone pilots now exceed 889 airmen piloting the C-17 transport and 803 flying the F-16, and the demand is stretching the air force’s ability to turn out pilots.

As the White House confirmed US special forces and marine engagement in the effort to capture the Isis stronghold of Raqqa this week, the focus on the effectiveness of drones may come under greater scrutiny.

According to James Lewis at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, the “real issue” with drones is not the cost in terms of civilian casualties but “the apparent ease with which the US violates other countries’ sovereignty”.

While in many cases permission may be covertly granted, he says, “there is the perception that the US can fly around and strike anyone and doesn’t pay attention to international law. We didn’t do enough to get ahead of that story, and civilian casualties are part of that.”

Despite its relatively puny 200lb payload and 1,000-mile range, the MQ-1 nonetheless reshaped the way the US fights, Lewis says. “The realization that you could conducted these operations remotely in remote areas came with the Predator.”

But the revolution of the MQ-1 may be better described as a step along a century-long road to put more distance between attacker and defender.

“There’s a long ethical debate about disengagement and distance from the battlefield but the real difference here is the unmanned part, and the combination of range and precision,” Lewis says.

As drone technology becomes more affordable and commonplace, the full measure of the changes in warfare ushered in by the Predator has yet to be felt.

“The MQ-1, and hanging a missile on it, really changed the way the US fought,” Lewis says. “This is still the technology that changed how people fight and we haven’t got the full advantage.”

Ask me anything

Explore related questions