Not yet a week since the triggering of article 50, and already hope of cordial negotiations seems optimistic. At the weekend, amid early jostling over the post-Brexit fate of Gibraltar, former Tory leader Michael Howard implied that one way to resolve that situation could be a war with Spain.

Thus far, the focus has been on the politics, the pounds, shillings and euros and the colour of passports, but in the search for common ground it’s worth remembering that the European Union treaty itself, in articles 3 and 167, places a duty on both sides in negotiations to take into account the need to “ensure that Europe’s cultural heritage is safeguarded and enhanced”. Here there is scope for a gesture that may allow talks to proceed more constructively.

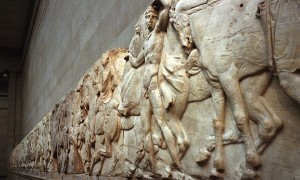

The most important symbols of Europe’s cultural heritage are the Parthenon marbles. Half of them are in the new Acropolis Museum, while the other half, ripped off the Parthenon by a Scottish diplomat, sit in a British Museum gallery. Putting the return of Lord Elgin’s stolen marbles on the Brexit negotiating table would lead both to a boon for Britain and a triumph for European enhancement of its heritage.

(“There is no doubt the marbles were stolen. Lord Elgin’s licence to remove “stones” specifically prohibited him from pulling down the superstructure of the building to rip off sculptures.“)

Reuniting the marbles is a cultural imperative, not so much for Greece (its current citizens are of doubtful descent from Pericles) as for Europe. United, they will stand as a unique representation of the beginnings of civilised life in Europe, 2,500 years ago. It will be like putting together a photograph long torn in half, recording people walking and talking, playing and (particularly) drinking. United in the custom-built modern museum beneath the Parthenon, the marbles will be the greatest artistic and architectural treasure on the continent.

There is no doubt that they were stolen. Elgin’s licence to remove “stones” specifically prohibited him from pulling down the superstructure of the building to rip off the metopes and sculptures. Before a parliamentary committee he lied outrageously, pretending to have acted only when he saw with his own eyes how they were being despoiled by the Turks.

This was a demonstrable falsehood, because he did not arrive in Athens until most of the marbles had been torn down by his workmen for his own profit, in breach of his duty as British ambassador. They are now vested by the 1963 British Museum Act in the trustees of the institution. But parliament can unvest them, by a simple amendment or a line in the big Brexit bill, and send them back to Athens as part of our final deal with Europe.

It cannot be said that the trustees have kept the marbles responsibly. They covered up the cleaning scandal for decades, after the marbles were scoured and scratched on benefactor Joseph Duveen’s orders. They still exhibit them in a gallery that commemorates Duveen – one of the most controversial, opportunistic art dealers of the 20th century. As for former British Museum director Neil MacGregor’s claim that they belong in a “something for everyone” museum – a quick thrill for tourists before they pass on to the Egyptian mummies via the Lewis chessmen – this is risible. They belong with the other remaining pieces of the astonishing frieze, under the transparent roof of the Acropolis Museum, looking up at the Parthenon and the blue attic sky.

(“Reuniting the marbles in Athens is a cultural imperative. They will stand as a unique representation of the beginnings of civilised life in Europe, 2,500 years ago.“)

Now is the time to offer to return them, as part of the Brexit deal. No one yet seems to have noticed the binding obligations on EU states and their negotiators, and on the UK (which remains a member state until it leaves) imposed by the EU treaty itself. article 3 sets down the duty to enhance Europe’s cultural heritage (obviously achievable by reuniting the marbles) and article 167 is specific. “When taking action under other provisions of the treaty” (ie under article 50) Brussels and all member states must “take into account” the objective of “conserving and safeguarding cultural heritage of European significance”.

There is no more significant cultural heritage than the Parthenon marbles, so the negotiators on both sides are bound to take their reunification into account. They are, of course, priceless, and a UK offer to return them should be accepted in return for major concessions.

It could become, in that dreadful phrase, a “win-win” situation: European negotiators would be praised for a unique cultural achievement, and the UK would earn not only large discounts, but also gratitude through an action most of its people agree with anyway, according to opinion polls. And the deal would have the advantage of not depending on the Greek government, which has been unavailingly requesting return, through diplomatic channels, since 1833.

Jean-Claude Juncker and his bureaucrats, and the governments of Germany, France and Italy in particular often refer to the importance to Europe of its culture – and they shouldn’t miss this opportunity to enhance it. The treaty itself, in my view, obliges them to put the reunification of the marbles on the negotiating table, and to give as much ground as possible to achieve their return to Athens. As for the UK, a willingness to surrender Elgin’s ill-gotten gains will win goodwill as well as concessions. Britain is leaving Europe, so it should leave Europe with its marbles.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions