The boat has become a symbol of the crisis in the Mediterranean: a creaky fishing boat, maybe, or a sagging rubber raft, crowded with refugees seeking a better life on a new shore.

It’s a powerful symbol, a marker for the thousands of men, women, and children who have died in recent years taking that risk. But it’s only one part of a crisis that now stretches across the Sahara Desert, through the lawless towns of North Africa, deep into organized crime rings in Europe.

Border patrols can’t stop it. Rescue missions can’t solve it. The problems facing the region, an ongoing RAND initiative shows, reach far deeper than Western governments have been willing to acknowledge. And that means fixing them will require reaching deeper still.

“It came from the frustration of seeing how oversimplified the problem was being presented,” said Giacomo Persi Paoli, a researcher with RAND Europe who led the project. “The problems are so deeply interconnected that we can’t solve them with this firefighting approach, putting out one fire at a time.”

He speaks from experience.

A Man with a Mission

It was dusk when the boat first appeared as a blip on the radar screen off the coast of Libya. On board the Italian naval frigate where Persi Paoli was a lieutenant, an emergency buzzer clanged as the captain ordered all hands on deck.

Persi Paoli could see hundreds of arms waving and reaching for help as the old wooden fishing boat came into view, rolling on the waves. He and his shipmates saved 400 lives that night, the first of what would be half a dozen rescue missions in which he participated. He remembers just hoping the little boat would stay afloat long enough as the waves pounded against its ragged hull.

“You could really tell that without you, these people wouldn’t have seen the light of the next day,” he says now. “We were desperately looking for these people, because we knew they were out there—women, kids—and they needed help.”

More than 5,000 people died trying to cross the Mediterranean last year, the deadliest on record. They came from the shelled neighborhoods of Syria, the desperate villages of Eritrea and Gambia. Somalia lost so many people to the sea that a warning began to make the rounds of Twitter there: #DhimashoHaGadan, or “Don’t Buy Death.”

That’s what people see on the nightly news: the bodies washed ashore, the crowded migrant camps, the boats. But Persi Paoli, who left the Italian Navy in late 2013 and joined RAND as a research leader specializing in national security, wanted to widen the lens. He called the project the Mediterranean Foresight Forum.

Follow the Money

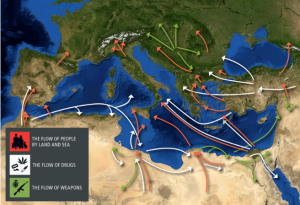

The researchers traced the roots of the crisis back to the shattered promise of the Arab Spring and the cratered cities of Syria and Libya, but also to European capitals too divided to act. They mapped the smuggling routes that now crisscross Africa and the Middle East, and then followed the money—billions of dollars every year—to criminal networks flourishing in North Africa and Southern Europe.

They showed that what may have once been many individual threats to the stability of the region have now merged, creating a cycle of unrest that feeds back on itself. In Libya alone, for example, the same black markets that provide fake passports and flimsy boats to migrants can also deliver hashish to European drug dealers and shoulder-fired missiles to Syrian fighters.

The grinding poverty of West Africa, the unrest of North Africa, and the terrorist threat of ISIS can no longer be treated as unrelated challenges, the researchers concluded. Those problems now all seem “to literally spill into the Mediterranean Sea,” they wrote, threatening the security and stability of the two continents that share its shores. The future of Europe has become inextricably linked by sea to the future of the Middle East and North Africa.

“All of these pieces get reported on, but nobody really weaves them together,” says Michael McNerney, a senior researcher at RAND, where he serves as associate director of the International Security and Defense Policy Center. “We need to look at the big picture, because if these problems continue to destabilize Europe and the region, that could be devastating for U.S. interests.”

“The crisis is getting worse,” he added. “But there is no one stepping up, offering resources or saying, ‘We need to radically reconsider what we’re doing.’”

The Immediate Need for a Long-Term Strategy

The United States, Europe, and NATO need to begin sharing intelligence in a way they have not managed since the migrant crisis began. They need to put more ships into the Mediterranean, more security agents at the border. But they also need to take an active role—through trade deals, for example—in stabilizing countries like Tunisia before they get pulled into the exodus.

The response from Europe and the United States has so far been too little, and too late. “What should have been rapid, robust engagement has often been more of a cautious voyage of discovery,” the researchers wrote in one of a series of recent reports. They suggested a “diplomatic surge” as a practical first step, to bring the nations of Europe, the United States, and NATO together to hammer out a single, unified strategy to address the crisis.

From across the Atlantic, the security and stability of the Mediterranean region might seem like a European problem, they noted. But what happens there—from Syria to Egypt to the beaches of Libya—has a direct impact on the security and interests of the United States. That should add some urgency to Department of Defense planning.

“The scale of the problem is unprecedented,” Persi Paoli said. “You can’t think of solving it just by managing the immediate crisis. It’s long term. But if you don’t start doing something, you won’t get any closer. In ten years, we’ll still be talking about the need for a long-term strategy.”

In Search of Safety and Stability

It’s been a few years since he was out there, scanning the horizon for the next boat. The enormity of what he saw still comes to him in unexpected moments: the people reaching from the water, the refugees huddled on deck. It was a reminder, as he worked on the Mediterranean Foresight Forum, of the stakes involved: not just the safety and stability of two continents, but the lives of hundreds of thousands of people who have made the journey, and thousands more who have yet to start.

“When my daughter was born and I held her in my arms, that’s when it really hit me,” he said. “There were pregnant women on those boats that we rescued. There were small children. They were people that, because of us, at least had a chance.

“Somewhere in North Africa or Syria, there are parents who are having to go through that, just to give their children that chance.”

Ask me anything

Explore related questions