Why should an exhibition marking 50 years since the restoration of democracy in Greece mainly consist of paintings, tightly packed in the basement of the National Gallery?

Democracy is not a sequential arrangement of events, nor is it organized. It thrives on divergence. It’s free, unpredictable, irreverent, and needs room to breathe. It includes everything. These were my thoughts as I left the museum, heading home.

I could imagine watching one of Aspa Stasinopoulou’s Super 8 films—some of the many she shot after the fall of the junta (the 1975 Polytechnic march, Theodorakis at the airport, Panagoulis’s funeral)—blocking the entrance, preventing us from viewing the rest of the exhibition. Yet Aspa is absent from the show, just as the exhibition itself lacks a cutting edge.

Sometimes absence can carry more weight than presence: “I always remember you leaving” (sic). I look at the black-and-white frame from a film in the exhibition’s hefty gold-covered catalog: a discarded garment on a chair, a plate with a piece of bread on the floor, posters on the walls, stacks of books, a wooden coat stand with a hanging coat next to the door. This frame from Frida Liappa’s film says more than the paintings in the Gallery. It speaks of youth, Athens, love, and politics. It speaks of the post-junta era while simultaneously saying nothing at all. It’s a silent frame. “I always remember you leaving.”

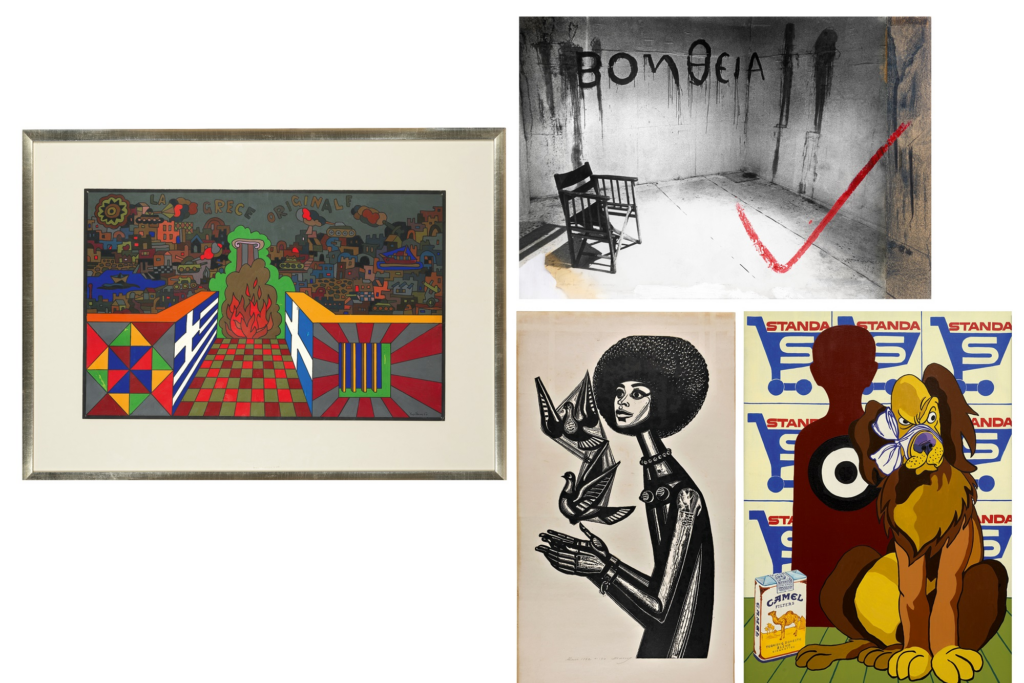

I thought how much more daring the exhibition would have been if the engravings by Katrakis or Tassos were missing. Then, their absence would be felt, and we wouldn’t be able to escape the deep lines of their lithographs or woodcuts. Yet, they stand there like hanging ghosts, remnants from past exhibitions.

Why do cinema, comics, photography, music, rock ’n roll, and the noise-making undercurrents of the city called “Subculture” shine in their absence? Where are the photographs of Tourkovasilis, the magazine Babel, or the band Trypes? I roam the space, nearing 50, and for a moment, I’m sure I was born and raised in a different country, in another time.

An exhibition that reflects half a century of paradox and contradiction should be aggressive, spiked, unorganized, and not afraid to take risks. It should showcase unknown, lost, and forgotten works, not just present the transition to the post-junta era. The following decades, at least artistically, were far more unstable, risky, unorthodox, and intriguing.

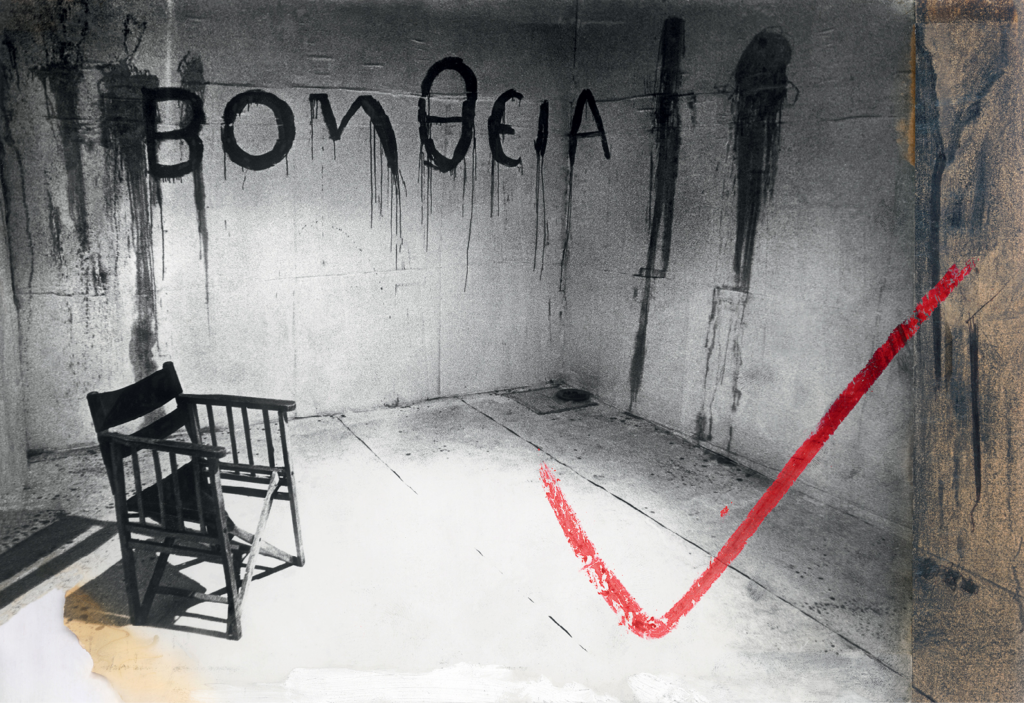

It’s no coincidence that I’ve been searching for Maria Karavela’s work for some time. Nowhere to be found. Her photos of performances, and panic-stricken actions from the years 1970-71, are in a glass display case in the darkest corner of the room. Her works remain threatening. And we are supposed to feel safe, and protected: “Help,” “L’Impossible.” I don’t think there’s a more relevant work than Karavela’s. It’s what’s left after the fire in her studio in 1996. The ashes are colder than death.

One can see artworks weary from the symbolism they have carried for so many years (Theodoros), works as dusty and rusty as the materials they’re made of (Alithinos), works naively obvious (Gaitis), works that appear dusty but retain their saving metal inside (Kaniaris), works that carry a permanent freshness, almost old and familiar (Akrithakis), hastily executed pieces with poor technique, yet their rawness sweeps us into what we feel now—chaos, numbness, and inertia—like the films of Lida Papaconstantinou. A naked female body, two tattooed male hands, circles of black paint around the vulva and breasts, a knife crossing and cutting bread. That’s all it takes.

And then? Small signs of vitality here and there, subtly undermining the exhibition’s narrative, executed by artists born before the war, locked into a time frame coinciding with the seven years of dictatorship. “Pro-Dictatorship,” I read on the cover of the first—and only—issue from the early days of Anti magazine, with a red circle on a black background, as if it had been etched by Lida herself.

I stand over Kapralos’s Wounded Soldier – Vietnam, looking at the sculpture’s right foot. Five toes, melted by napalm, form a bronze sole, hollow at the heel. It feels like a secret exit, one that could lead me out of the exhibition’s closed loop, straight to Vasileos Konstantinou Avenue. I take out my phone and photograph it. Again and again. Two metal bridges support the two sides of the sole. Then, I lean over the headless body of the warrior, with an arm resembling a fish fin or sickle. I get so close as if trying to ask: “And us? Where are we in this exhibition?” I take the elevator to the ground floor, pass through the glass door, and find myself under the scorching midday sun, with no answer.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions