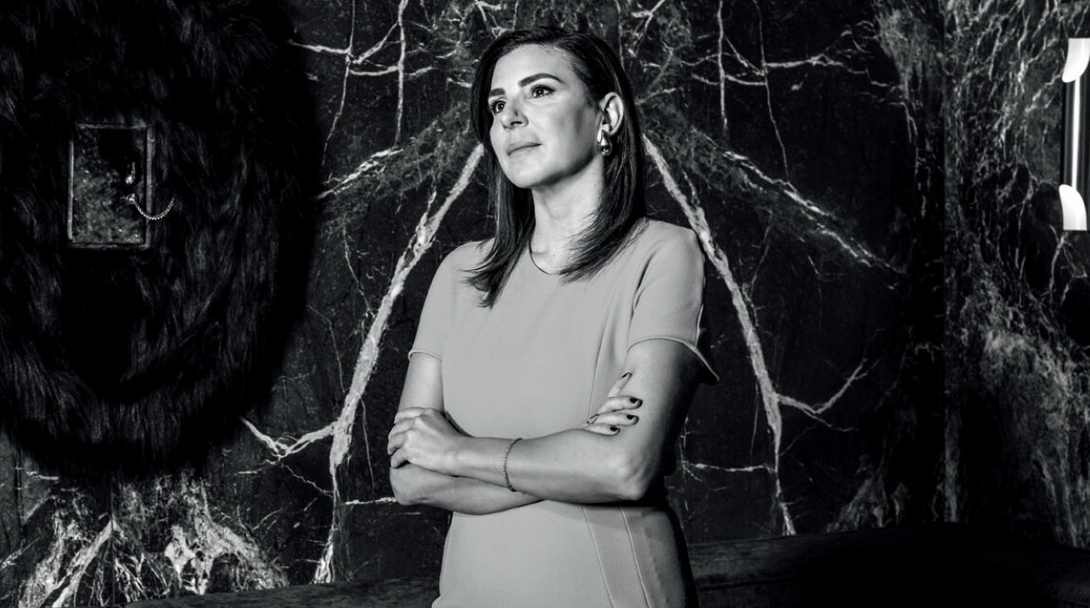

What is Greece‘s position and, more importantly, what are its prospects in the new digital world, which is evolving at dizzying speeds? Is Artificial Intelligence coming to turn many of us into unemployed workers, or is it creating new employment opportunities? How can someone invest in AI and make money? Peggy Antonakou attempts to offer rational, convincing answers to a series of questions about the present and, more importantly, the future.

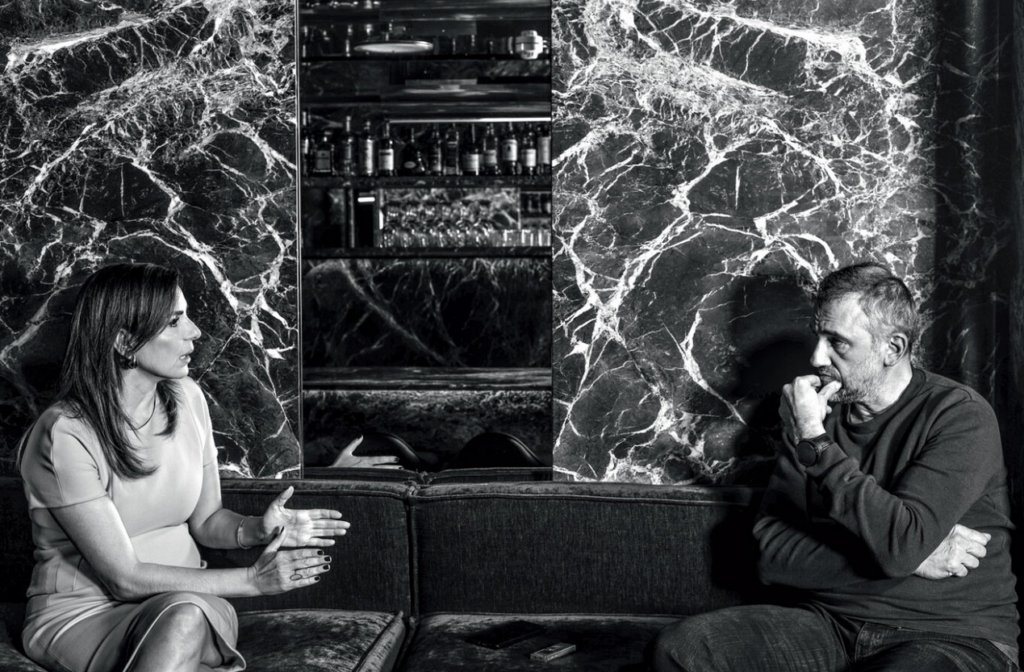

VASILIS TSAKIROGLOU: Google’s history in Greece since 2004 roughly coincides with the launch of Proto Thema. If you don’t mind, we could start our discussion with the basics, with some perhaps simplistic questions. For example, why is Google in Greece in the first place? And in connection with that, why are you, a Greek woman, the head of Google Greece and Southeast Europe?

PEGGY ANTONAKOU: In a way, the essence of the answer to both parts of your question is the same. And the answer is simply that Google saw potential for growth and development — both in Greece and, since you’re asking, in me. I would even say that in my case, the feeling was mutual, because when the opportunity arose for me to transfer to Google, I didn’t have a serious reason to leave the previous company I worked at. I was very satisfied there and had a very successful career. However, I felt that Google presented new challenges, that I could learn more and new things, and that I could also contribute in my own way.

Now, as far as Greece is concerned, indeed, as you suggest, there was no particular reason for Google to establish a base in our country, in the sense that Google’s services are inherently global and not bound by geography. But that is only superficially true. Google’s presence in Greece has strategic importance. It’s no coincidence that Greece is one of only seven countries chosen and trusted by the European Union for the establishment of Artificial Intelligence factories. If we think back to 2000 or 2005, when your newspaper began publication, how reasonable would it have sounded to imagine a scenario where Greece plays a leading role in the evolution of digital technology in Europe by 2025? Back then, if you recall, everyone talked about the “train of information technology” that Greece must not miss — but it seemed certain we would. I don’t think anyone was optimistic. Yet here we are — Greece made it.

V.T.: Allow me, please, to interject one more naive question: How can someone make money from Artificial Intelligence? Let’s say there’s an entrepreneur who is completely unfamiliar with AI. Still, they hear that in a few years, the market in this sector will have grown to hundreds of billions or even trillions of dollars. Where should they invest to profit from this “AI” that suddenly seems to be everywhere around us?

P.A.: Artificial Intelligence is now a fundamental technology shaping the future of the economy and entrepreneurship. Its operation and use are based on three core business models. On one hand, you have the large tech companies, like Google, which act as primary “producers” of AI. They invest massive resources into the research and development of new algorithms, platforms, and tools, accelerating the spread of this technology and making it accessible across various sectors. At the same time, AI serves as a tool supporting every industry — from manufacturing and healthcare to transportation and the public sector.

It can predict protein structures, issue early warnings for natural disasters, and accelerate scientific progress. It also reduces costs and increases efficiency by optimizing processes such as equipment maintenance, fuel savings in maritime transport, and modernization of public services. AI can be compared to electricity: you can see in the dark thanks to a lightbulb, but without electricity, the bulb is useless. Moreover, AI creates new business opportunities and forms a key infrastructure for developing innovative models, especially for startups. Today, it functions like the Internet or electricity, supporting technological platforms regardless of the sector. Its value lies not only in profitability but in boosting efficiency and shaping a more sustainable and innovative future.

V.T.: What is your personal contribution to the relationship between Artificial Intelligence, Google, and Greece?

P.A.: I try to serve as Google’s ambassador in Greece, but also as Greece’s ambassador within Google. Precisely because our country has real potential. What’s great about Google is that it doesn’t just invest in facilities, data centers, and technology, but most of all, it invests in the human capital of every country where it operates. So, in this role, I try to facilitate and accelerate the strengthening of ties, to help build collaborative networks, and to support initiatives that push us forward. On this basis, Google works with the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of the Interior, the University of Athens, SEV (Hellenic Federation of Enterprises), and others.

We’ve already trained, completely free of charge, tens of thousands of people in Greece in the development of digital skills — students, private and public sector employees, small and larger businesses. Again, 20–25 years ago, who would have imagined that public servants in Greece would be trained in AI applications? And yet, that’s exactly what’s happening. It shows there’s a willingness on the part of employers, along with awareness and vision.

V.T.: So, in your view, Greece is placing emphasis on advanced digital technology — even though, for example, when it comes to basic digital skills, Greeks are about 3% below the EU average?

P.A.: According to a study conducted by Implement Consulting Group on behalf of Google, there is a well-founded forecast that Artificial Intelligence — and specifically Generative AI — can contribute to Greece’s economic growth, increasing GDP by 6% annually over a decade. Of course, this depends on certain conditions: that AI is widely adopted in both the public and private sectors, that there is functional streamlining, cost-cutting, and the creation of new economic activity. However, if we don’t act swiftly as a country and fail to adopt these innovations, that 6% could shrink to just 1%. AI is not an opportunity that remains available forever, like an unlimited resource.

Beyond that, I agree that Greece started from a low point — that’s true. But the leaps we’ve made as a country are massive. One characteristic example: During the COVID-19 pandemic, I hosted a friend from the U.S. in Greece. When we went out to eat and were asked to show vaccination certificates, my friend pulled an A4 paper from her bag, unfolded it, and presented it. I just showed my phone — the app created by the Greek government. Why? Because little Greece had managed to outpace the U.S. in digitalizing COVID-19 vaccination certificates. The Ministry of Digital Governance was created only nine years ago. And today, not only does it exist, but it is often considered a reference point internationally, as Greece’s public sector has generally moved faster in digitalization than the private sector. Especially in relation to Artificial Intelligence, Greece is actively participating in the global discussion. We’ve already defined national principles and ethical foundations for its use. We have a respected presence in industry forums and the international dialogues around AI.

V.T.: So that means many of us won’t lose our jobs because of Artificial Intelligence?

P.A.: No, absolutely not. In Greece, given the way our national economy and employment are structured, 62% of jobs won’t be affected at all by AI — we’re talking about professions like cooks or nurses, which by nature aren’t within AI’s scope of application. Around 32% of jobs in Greece will be positively impacted by AI, through increased productivity, speed, and higher quality services. The share of jobs that will be eliminated because they’ll no longer be relevant — like data entry roles — is about 6%. For those jobs, we all bear a collective responsibility — the state and digital technology organizations alike — to retrain people whose roles will become obsolete. We must equip them with new skills so they can find new employment. The figures I mention are findings from the major study I referenced earlier, which we at Google conducted specifically on Greece and Artificial Intelligence.

V.T.: Could you have imagined, back in the early 2000s, that by 2025 we’d be worried about robots taking our jobs?

P.A.: Not in the slightest. If we go back about 25 years, I was in the U.S. as a student. At that time, the challenge for us was to try to predict the future, which clearly involved the explosive growth of the Internet and digital technology. But the word “to Google” didn’t even exist yet as a verb. And now I think that our kids, thanks to AI and autonomous driving, will never even need to learn how to drive. That was pure science fiction in 2000 — but now, it’s almost a reality.

V.T.: In light of the progress of digital technology, what was your everyday life like 20–25 years ago compared to now?

P.A.: Back then, to communicate with friends and family in Greece from the U.S., I mostly used fax and email — though, of course, you had to own a computer, have a dial-up internet connection, and so on. There were some early chat engines that had just begun to emerge. Also, in 2001, the 9/11 attacks on the Twin Towers happened. I was a graduate student during that extremely difficult period for the U.S. As soon as I graduated, I started job hunting to pay off my student loans. I had to work — not just out of necessity, but also because I wanted to gain experience. So, I began sending out my resume, thankfully via email, to various companies.

One of them, Dell Computers, invited me for an interview at their headquarters in Austin, Texas. At the time, I was living in Michigan — on the other side of the country. I flew to Austin without knowing anything about the city. I stayed just a few hours and left, having seen very little — basically just the airport and the route to and from Dell. At the time, if you didn’t have a travel guide or maps, you were totally lost. In fact, when my mom in Greece heard I was going to an interview in Austin, Texas, she panicked. She thought I was headed to the Wild West — cowboys and shootouts in the streets! Can you even imagine that today? Now, from my phone, I can ask Google’s new AI tool, Gemini, for any information about any place in the world. I can see the landmarks, the best restaurants based on reviews — I can even put on VR glasses and take a virtual trip, as if I were actually there.

V.T.: All this rapid progress in digital tech, AI, etc. — is it leading to something good? Are you optimistic about the future? Is there anything you’re worried about?

P.A.: I’m absolutely optimistic. Just last year, for example, the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to Demis Hassabis, the leading researcher at DeepMind, which is part of the Google group. Hassabis isn’t a chemist — he’s a computer scientist — and that alone shows how crucial a role technology now plays in our lives. Because using AI, Hassabis essentially decoded a piece of the genetic code. The time required to achieve such a breakthrough is now vanishingly small compared to what it would have taken 20–25 years ago.

The decoding of the protein creation mechanism — essentially what Demis Hassabis discovered — opens up vast new horizons for science, such as the creation of personalized medicine. Imagine that, thanks to technology, treatments in the future will be tailored to each individual based on their DNA — something unthinkable 25 years ago. And even today, with AI applications in breast cancer diagnosis, we can prevent painful and potentially deadly ordeals for ourselves and our loved ones. Also, technology eliminates many inequalities — though, unfortunately, not yet the major social inequalities. But consider that in today’s digital and interconnected world, a small country like Greece has exactly the same opportunities for access, growth, and visibility as any other country on the planet, regardless of economic power, population, or size. That’s why I believe digital technology is a catalyst for democratization in our world.

V.T.: Since a major part of your work involves managing human resources, what would you say is the main goal of management?

P.A.: It’s what the Americans call a “win-win.” Striving for a relationship with your team where everyone benefits — both them and you. Only then will everyone give their best and create mutual value. That’s the only way we move forward. And always, only happy teams deliver results. But to achieve a win-win, you always have to remember that people are much more than the work they do — even if that’s what takes up most of their day. Personally, I never stop thinking — it’s a flaw of mine — and I usually get my best ideas while swimming, going for a bike ride, or during yoga.

V.T.: Going back to the original, somewhat naive question: Why do you think Google chose you specifically? One would assume that there were dozens of candidates for the position of General Manager for Google in Southeastern Europe — many from countries with markets far larger than Greece’s. So, what was your advantage?

P.A.: I don’t remember off the top of my head how many millions of résumés Google receives every year. And correspondingly, how difficult it is to get hired. In my case, I joined Google after a very specific career path, at Microsoft and before that at Dell Computers. At Dell, I was responsible for the Italian market. It was quite unusual for a Greek woman to be general manager in Italy — while the opposite wouldn’t have raised any eyebrows, say, an Italian leading in Greece.

Also, Dell had to enter the Italian market literally from scratch, so I had to hire people and essentially build the entire Dell Italy operation from the ground up. We succeeded, delivered fast, above-target results. A similar thing happened at Microsoft Greece. In fact, in 2016, the Greek office was awarded internally as the top-performing branch globally for Microsoft. And that was the year after Greece had capital controls — I remember we even had to arrange for an armored cash delivery to pay employee salaries. I’m trying to answer indirectly what Google saw in me rather than another candidate. I’d say there are two key factors in my case: One is that, clearly, I had delivered results in previous executive roles, so I had, let’s say, the necessary credibility — a proven track record. The second is that I always show a lot of enthusiasm and passion for whatever I take on. If I see an opportunity, I’ll go for it — even if I don’t know exactly how I’ll handle it. I usually figure that out along the way.

V.T.: Would you say that Greece — or the world in general — has become a better place over the last 20–25 years?

P.A.: That’s a tough question to answer briefly. What I can say, though, is that all indicators show the world has objectively gotten better. Poverty levels, child mortality — almost all the core indicators of the human condition, broadly speaking, have improved over the last 25 years.

So yes, it seems we’re in a better place now than we were in 2000 or 2005. That’s not to downplay or ignore the very serious issues that still exist — wars, social inequalities, the climate crisis, major diseases, and more. However, I believe we now have more tools in our arsenal to tackle these problems. But above all, I think the key is that human beings are the most adaptable species on this planet. And we always find solutions — even if we’re the ones who created the problems in the first place!

Ask me anything

Explore related questions