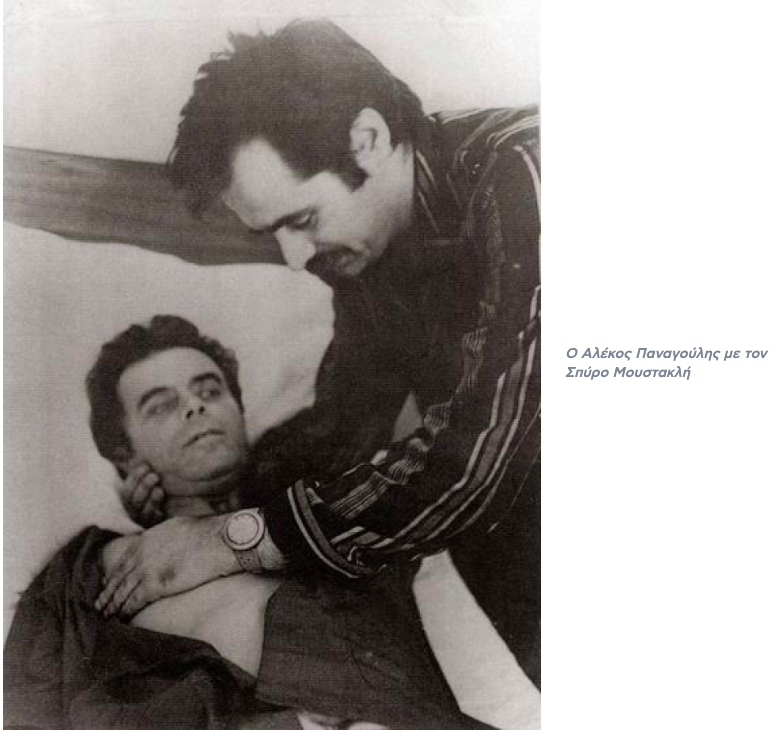

“I want to give with the same strength I had at the beginning. I want to win since I cannot be defeated.” The verse, written in blood by Alekos Panagoulis on a piece of gauze during his months-long torture at the hands of the military junta, captures better than anything the unbreakable spirit of the thousands who stood upright before a tyrannical regime.

According to official records, from 1967 to 1974 more than 90,000 people were arrested. The vast majority endured beatings, electric shocks, mock executions and every imaginable cruelty.

Numerically, they may appear few compared to the general population—but they were enough to defend the honor and dignity of a people who have shed rivers of blood for freedom and democracy.

Αmong them were the pioneering young men and women of the era—those who refused to accept darkness and fought for the light. Alongside them were thousands of democratic citizens and military officers who spent long periods in sunless cells and camps.

These days, 52 years after the heroic Polytechnic uprising, our minds return to the places where these young people—along with countless older fighters—suffered under the dictatorship. Places where historical memory remains alive.

And even if half a century later nothing seems to remind us of that pitch-black period—culminating in the violent November of 1973 and the massive commemorations of the early Metapolitefsi years—the sites of sacrifice, whether still standing or known only through documents and testimonies, remain essential cores of collective self-knowledge. They must unite, not divide us. Above all, they remind us that nothing is granted—and nothing is to be taken for granted.

Special Interrogation Department-Greek Military Police (E.AT-ESA)

From the infamous E.AT-ESA—today Liberty Park on Vasilissis Sofias Avenue—to Bouboulinas, the Averoff and Oropos prisons, KEVOP in Haidari, Bogiati, Gyaros and the other islands of exile—these were the scenes of unspeakable pain for those who “did not comply with instructions.”

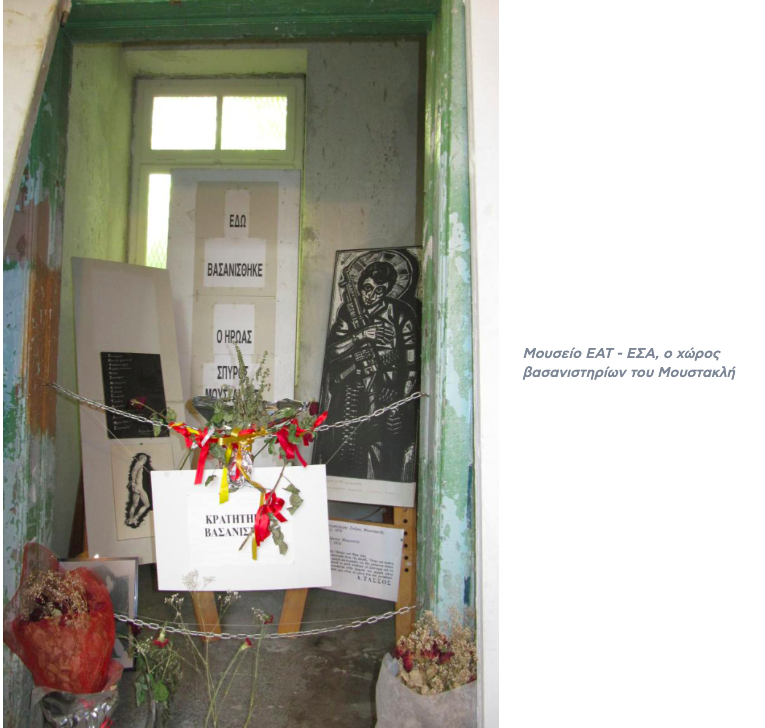

On a bright midday in 2024, during a visit to the former EAT-ESA headquarters—now a museum—a young woman approaches the entrance holding a small dog. The dog stops at the threshold, bristles, and begins barking furiously. It refuses to step inside, as if sensing, even decades later, the innocent blood and brutality soaked into the walls.

EAT-ESA, the Special Interrogation Unit of the Greek Military Police, established in 1951, played a central role in repressing and terrorizing the population during the junta years. Its very name inspired fear.

But it did not break the spirit of those held there—many of them arrested before and after the Polytechnic uprising.

Some of the most notorious cases include Alekos Panagoulis, tortured after his 1968 attempt to assassinate dictator Georgios Papadopoulos; Army officer Spyros Moustaklis, arrested for the Navy mutiny in May 1973, tortured for 47 days until he was left paralyzed and voiceless; and Air Force colonel Tasos Minis, tortured for 111 days.

Women were also among the victims—young students who stood as unyieldingly as any man: Melpo Lekatsa, pharmacy student and member of the Polytechnic infirmary, held at EAT-ESA; Nadia Valavani, tortured at Bouboulinas; and many others.

Methods included severe beatings, electric shocks, mock drownings, solitary confinement, deprivation of food and water, and more. Many suffered lasting physical and psychological damage; some died.

After the fall of the junta, some buildings were demolished; in 1997 four were declared protected. The main detention and interrogation building now houses the Museum of the Anti-Dictatorship Struggle, overseen by the Association of Imprisoned and Exiled Resistance Fighters. In its courtyard stands a bust of Moustaklis bearing the inscription: “For all who suffered here.”

Bouboulinas

A heavy history weighs on the buildings on Bouboulinas Street, right behind the Polytechnic—one of the most notorious torture sites of the dictatorship.

The building at 20–22 Bouboulinas, designed in 1932 by Cyprian Biris, once belonged to Konstantinos Logothetopoulos, a medical professor who later became a collaborationist prime minister during the Nazi occupation. After the war he was convicted of treason.

From the 1950s, the building housed the dreaded KYP, the Central Intelligence Service, which was highly active during the junta.

But the true torture chamber was next door, at 18 Bouboulinas, also once owned by Logothetopoulos. Originally a clinic, later a hotel and court building, it became the headquarters of the General Security Sub-Directorate during the dictatorship.

It was here that infamous torturers—Mallios, Babalis, Spanos, Lambrou—inflicted unimaginable horrors on hundreds, including many arrested during the Polytechnic uprising. Twenty-two people died during detention; at least 21 more died shortly after release.

On the building’s notorious rooftop laundry room—“the most famous laundry room in the world,” as Periklis Korovesis wrote—victims were beaten, burned with cigarettes, had their nails and hair torn out, were subjected to sexual torture, mock executions and more. Neighbors heard the screams day and night. To muffle them, interrogators ran a motorcycle engine at full throttle on the roof, or timed the blows with the bells of a nearby church.

The Aσφάλεια (Security Police) remained there until 1971, when it moved to 14–18 Mesogeion Avenue, now home to the General Secretariat for Research and Innovation. The torture building at 18 Bouboulinas was demolished shortly before the junta fell; a residential block stands there today.

The 20–22 building later passed to the Communist Party (KKE) and eventually to the Greek state, now housing the Ministry of Culture.

Other Torture Sites

Torture took place in dozens of facilities across the country—police stations, Security police buildings, the Gendarmerie headquarters in Perissos, the General Security Sub-Directorate of Piraeus, and many more.

Hundreds were tortured for months at the former 505 Marine Battalion camp in Dionysos, notorious for mock executions—victims included leftists like Christos Rekleitis and decorated officers loyal to democratic principles.

In the Military Prisons of Bogiati, Panagoulis suffered his worst torments in a cell described as a tomb. There, Kostas Kappos nearly died after torturers hung 50-kilo cement sacks from each arm and burned his abdomen with lime.

Others were held at KEVOP in Haidari, the historic WWII martyrdom site, and at the Military Police Training Center in Goudi, where mock executions and forced feeding were routine to keep detainees conscious for further torture.

Even naval facilities were used—such as the holds of the destroyer Helli II.

The Prisons

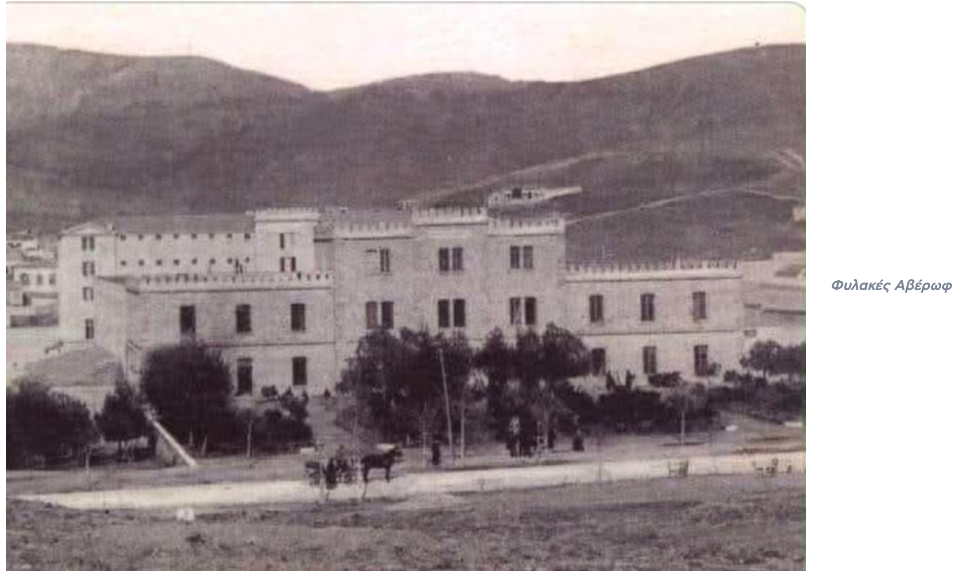

The Averoff Prison, across from Panathinaikos stadium, built in 1892, became a de facto political prison through decades of turmoil—from the National Schism to the Metaxas dictatorship, the Occupation and the Civil War. During the junta, it held political prisoners including Andreas Papandreou, until its closure in 1971. It was demolished in 1972 to make way for the Supreme Court building.

The Oropos Prison also has a long history—once an orphanage, then an agricultural prison. Under the junta it held hundreds of political prisoners, including Manolis Glezos, Charilaos Florakis, Andreas Lentakis, and Mikis Theodorakis, who immortalized it in his songs “Don’t Forget Oropos” and “Because I Did Not Comply.” The site is now being transformed into a Center for History, Democracy and Culture.

In Thessaloniki, the Eptapyrgio Prison (Yedi Kule) continued its long, dark tradition of political imprisonment and torture.

The Islands of Exile

A separate chapter belongs to the exile islands.

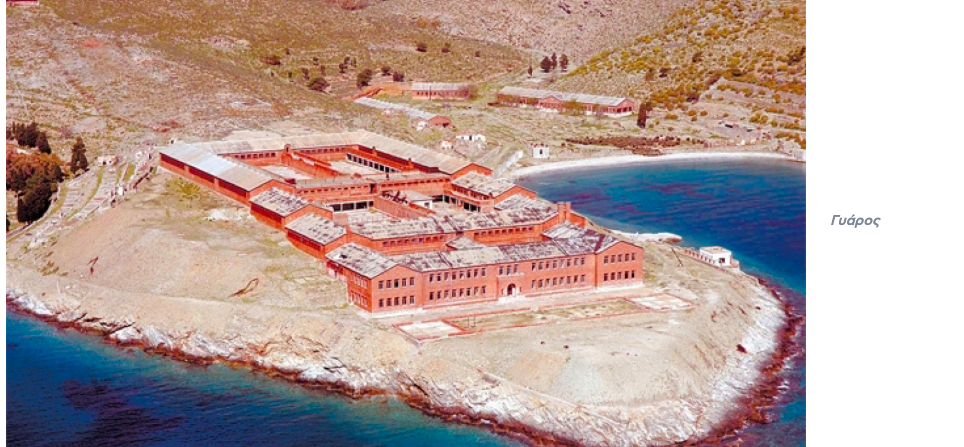

During the junta most political prisoners were exiled to Gyaros, though many were also sent to Partheni and Lakki in Leros, Trikeri, Kythera and others.

Gyaros operated as a prison island from 1947 to 1953 (with detainees building its structures themselves), reopened from 1954 to 1961, and again from 1967, when the junta exiled more than 8,500 people there—including 300 women. Labeled “Devil’s Island” and “Island of Death,” it became infamous worldwide for its inhumane living conditions and led to the junta’s condemnation by the Council of Europe.

After 1968 most prisoners were moved to Leros, where around 4,000 were held between 1967 and 1971. Among them were prominent figures like Yannis Ritsos and Manolis Glezos. The Lakki camp later became notorious again in the 1980s when part of it was used as a psychiatric wing where patients were kept naked in shocking conditions.

The old Italian barracks at Partheni were unfit for human habitation—windowless ammunition depots where prisoners were crammed together.

Keeping Memory Alive

This list cannot possibly include every place where thousands—regardless of political background—were stripped of their freedom, subjected to the twisted cruelty of their tormentors, or died in damp and dark cells to keep hope alive.

Today, what matters most is to keep their story alive in our collective memory.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions