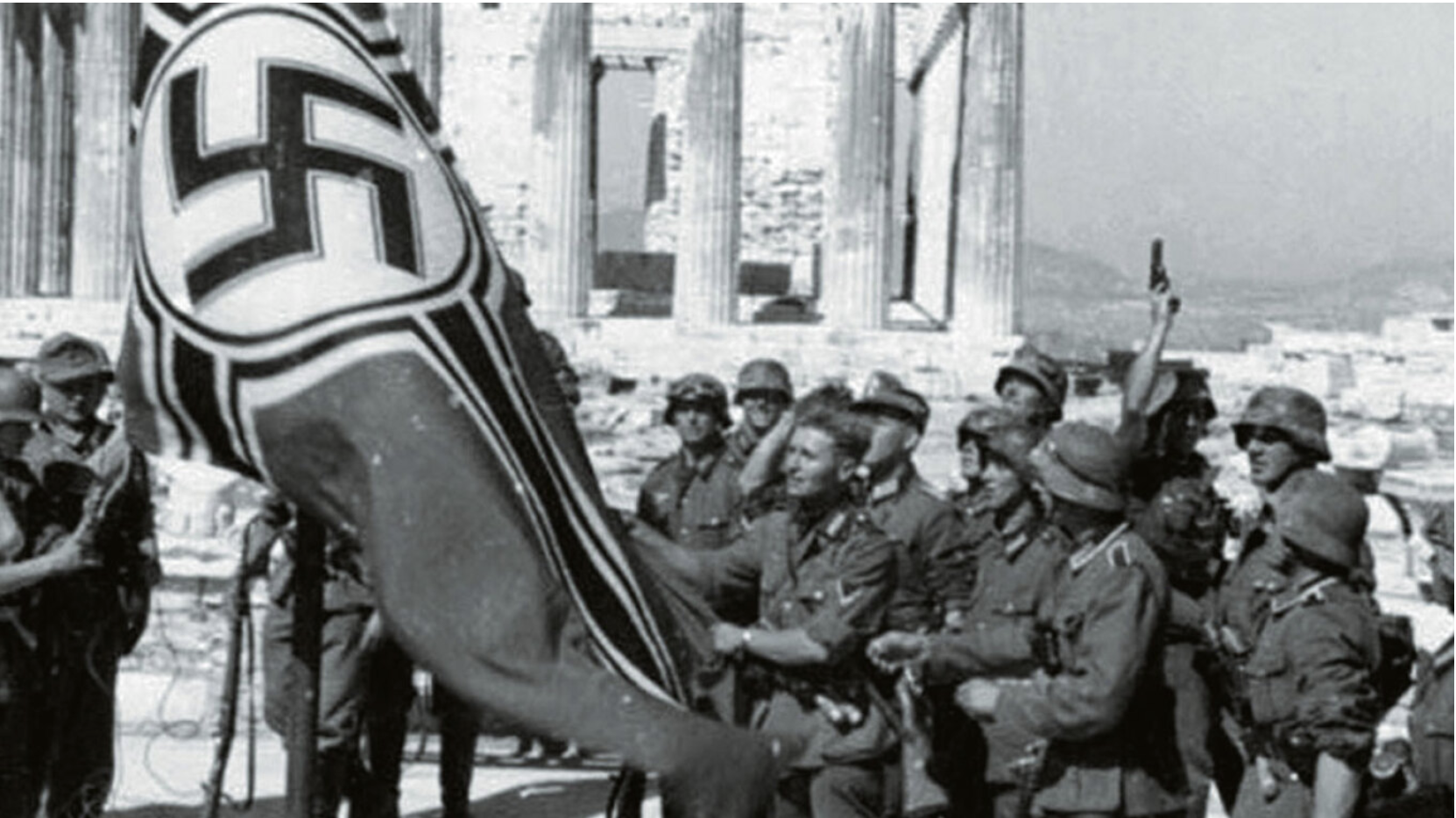

Five thousand dead from executions and battles, 45,000 from famine, people who, driven by starvation, ended up eating not only the occupiers’ leftovers but even stray animals to survive, and others executed merely for breaking store hours or fishing outside designated zones in the sea—children who were forced to eat even the vomit of the enemy outside restaurants—these are some of the meticulously documented facts and conclusions that Menelaos Charalambidis presents in his extensive studies on Athens during the Occupation. His latest book, co-edited with Stratos N. Dordanas, is titled The Long Night of the Occupation – Human Losses and Material Destruction in Occupied Greece (1941-1944).

Four years were enough not only to devastate Athens but the entire country. The incalculable damages left Greece without essential infrastructure for the future. Parts of the road network and central streets were destroyed, mineral wealth was looted by the occupiers, and significant losses occurred in archaeological treasures that could not be hidden in remote locations, as happened with the National Archaeological Museum.

Specifically, in central Athens and the wider Attica region, the destruction and losses were truly enormous: corpses lay even in the middle of streets or next to garbage, and there were so many that gravediggers often had to be paid extra for the extended hours. The few restaurants and cabarets that remained, mainly in the city center, existed solely to entertain occupiers and their collaborators. Any operating pastry shops, especially during the two years of severe famine, had to hide their sweets for fear of vandalism.

The first scientific study of the Occupation

These are the conditions that Charalambidis has documented through his years of research on Athens and occupied Greece. Together with a new generation of historians, he has undertaken a scientific study of the Occupation period to uncover the truth. For example, overturning exaggerations in studies published immediately after the war or in works like Konstantinos Doxiadis’ research, which claimed over 150,000 deaths from famine—the primary cause of death—Charalambidis’ team draws new conclusions based on extensive evidence, particularly regarding human losses beyond Attica.

Within Attica, losses are studied in detail, extending from famine and mass executions to roadblocks, accidents, stray bullets, internal conflicts, and diseases like tuberculosis caused by poor nutrition. These conditions also gave rise to resistance organizations: in his chapter The Cost of the Occupation: Human Losses in Attica 1941-1944, Charalambidis notes that the first resistance attempts appeared after October 1941, when the severe famine began to sweep through the city and surrounding areas.

Resistance was, in a sense, unavoidable. Even those willing to show “obedience” found themselves in conditions that left no choice. Charalambidis writes:

“Attica paid a very heavy price in human lives. Its population suffered the greatest blow during the famine (winter 1941-1942), the largest humanitarian crisis to strike an occupied European country during World War II. The exploitation of productive resources, wealth, and labor imposed a regime of terror by the occupiers, aiming for absolute compliance through extremely violent suppression of even minor signs of disobedience. This resulted in significant civilian casualties from the very first days of the Occupation.”

Dead next to the garbage: The truth about the horror of occupied Athens

Specifically, Charalambidis attempts to record the number of human losses in Attica caused during the Occupation by Nazis, Greek collaborators, and the actions of the Greek resistance. However, as he notes, the issue is not only quantitative but qualitative: the scale of violence and the ease with which the occupiers exercised it—often for the slightest reason—was shocking. His extensive research was necessary, as even 80 years after the war, the state has not officially documented Occupation losses. His work fills a gap that earlier researchers attempted to cover either through rough estimates or arbitrary conclusions.

The primary sources used include:

“Extensive series of death records, forensic reports, burial books and permits, ambulance call logs, court records and decisions, nominal lists of victims, newspapers, and relevant bibliography.”

This research led to the most complete record to date of losses in the country in his historical books, documenting not only the human element but also material, psychological, and qualitative consequences. Mental health is a central factor, with a remarkable study by neurologists and psychiatrists who served in Athens hospitals during the Occupation (1947), documenting the hidden death of mental collapse and insanity, as fatal as death by famine.

Executions for trivial reasons

Executions were not always political or retaliatory. Often they occurred without reason or because citizens unknowingly entered prohibited military zones, turning the city into a constant death trap. Charalambidis gives examples:

“On 12 October 1941, sixty-year-old Elisavet V. was collecting wood in Skaramanga. Unknowingly, she entered a restricted German naval zone and was shot dead by a German sentry. Around two weeks earlier, on 29 September 1941, twenty-six-year-old fisherman Dimitrios P. was killed in his boat by a German seaplane while fishing in a prohibited area off Palaio Faliro.”

Many deaths also resulted from executions of residents forced to steal to survive. The famine caused widespread theft, particularly from military warehouses in airports (Hassani/Elliniko, Eleusis, Tatoi), Piraeus port, Salamina naval base, and vehicle maintenance depots in Goudi. For thousands of Greek workers in these facilities, stealing and selling supplies provided essential funds to survive, often at the cost of death or capture by German guards.

On 29 October 1941, in the first mass execution of the Occupation in Attica, five workers were executed for stealing fuel and oil from a German warehouse. During the Occupation, at least 100 people were killed during thefts or executed for robbery, classified as sabotage by the occupying authorities.

Transportation was nearly impossible: citizens walked everywhere, trams and suburban railways ran intermittently, buses were rare, and the infamous “gazozens” burned dangerous fuels. Countless accidents occurred, often from drunken or negligent Germans or intentionally targeting unsuspecting passersby.

The dead of taverns and bars

Charalambidis documents incidents such as:

“On 19 October 1943, a drunken German officer entered a central Athens bar. The owner’s 23-year-old brother explained that the bar was closed due to curfew. Enraged, the officer shot bottles, mirrors, lights, and finally killed the young man. On 2 May 1944, German forces attacked a tavern in Nea Sphagia, throwing a grenade inside and shooting indiscriminately. Nine civilians were killed; ELAS fighters had left the scene hours earlier.”

These examples show the arbitrary nature of German executions, which intensified as the war neared its end. Most deaths occurred in the final war years, 1944–1946.

The 83 executed in Egaleo

Beyond organized mass executions like the Kokkinia roundup, which resulted in the highest human losses in Athens, further atrocities occurred. On 17 August 1944 and 29 September 1944 in Egaleo, Germans killed dozens of civilians after a clash between ELAS youth and German motorcyclists. They surrounded homes, set them on fire, and killed at least 83 residents. Three days later, ELAS captured local munitions facilities, prompting German forces to return, shell the area with mortars, and burn homes.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions