The walls of Vienna trembled on 27th of September, 1529, as strange music echoed close by. The sound of hundreds of drums stopped the heartbeats of the Austrian defenders. Also, the loud horn-like noise of the zurna pierced their souls, bringing fear of the unknown; of a distant menace coming from afar – The Janissaries.

Beating drums accompanied the steps of a marching horde. The force approaching was the Janissaries. An elite Ottoman army unit, led by the Sultan himself ― Suleiman the Magnificent. They were known to wreck havoc and showed no mercy to anyone who opposed them. Disciplined, loyal and skilled the Janissaries represented the crown jewel of the expanding Turkish empire.

Long before the Ottoman Turks were besieging Vienna, this particular breed of warriors was invented as the Sultan’s own bodyguards. They were created out of necessity in the late 14th century, during the rule of Sultan Murad I. Before their formation, the Ottoman army relied on a loosely tied allegiance of tribesmen foot soldiers who proved to be unpredictable in their loyalty and efficiency. The bulk of the rest of the army was composed of Turkish noblemen, who exclusively belonged in the cavalry ranks.

Murad I faced a rising threat from his aristocracy and a growing number of Christian subjects as the Empire expanded to the Balkans and the Caucasus. He devised a plan of how to solve both problems with a single blow.

The Ottoman society functioned on a complex slave-owning system. This allowed the enslavement of Christians and other non-Muslims. But this slavery nurtured a hierarchy within that enabled slaves to advance through either the army ranks or those of a civil servant. This meant that a non-Muslim could start off as a mere slave, and eventually become the Grand Vizier; which was a position second only to the Sultan.

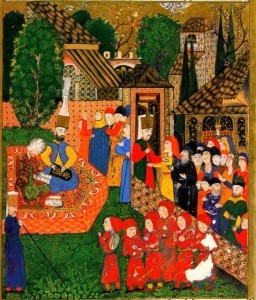

(Registration of boys for the devşirme. Ottoman miniature painting from the Süleymanname, 1558)

In the 1380s Murad adopted the devşirme system or the “tax in blood.” So-called among the Christian families of Anatolia, Balkans, Armenia, Georgia, etc. for it meant they were obliged to give their most able sons, preferably 8-14 years of age, into the Sultan’s service. The boys were then converted to Islam, circumcised and put through strict training that demanded physical and mental readiness. At first, this tax was strongly rejected by the Christian population. Soon, though, it became apparent that service in the Ottoman army could provide far more benefits than life in the slums of the Christian quarters.

In the early days of the devşirme system, all Christians were enrolled indiscriminately. As time went on, those from Albania, Bosnia, and Bulgaria were preferred, for they demonstrated the best results in adapting into Turkish society.

They were sworn to celibacy so they would leave no descendants. They were also prohibited from growing a beard or taking up a skill other than soldiering. Their loyalty was to be unquestionable. They were called Janissaries, or the “New soldiers” and represented the newly reformed infantry of the Empire. The unit was a few thousand strong during the first years, but in the early 16th century, their numbers were around 40,000.

Sultan Murad I thus secured himself among the power-hungry noblemen who were often plotting behind his back. The Janissaries were organized more like a religious cult than a military unit. Their fanatical approach to warfare corresponded with their extreme adoption of Islam after conversion.

(A 15th-century Janissary drawing by Gentile Bellini)

They were the Sultan’s personal favorite as they also served to bring back balance into the aristocratic society. Since they came from a poor social background, the Janissaries had to earn their benefits through accomplishments. These new recruits had to prove their worth, while the noblemen enjoyed privileges from birth.

The Janissaries were dressed in distinct uniforms, marched with a military orchestra called the Mehtar and were paid regular salaries. Even though they weren’t free men, their service was considered prestigious. The training took years. The boys would become men through severe discipline and at the age of 25 to 27 they would become the soldiers of the Empire.

They were the first to adopt firearms in the Ottoman army and had a well organised and well supplied medical treatment and logistics system.

(Janissary rifles from the year 1826)

In combat, they used axes and kilijs; a type of sabre. Originally, in peacetime, they could carry only clubs or daggers, unless they served as border troops. Turkish yatagan swords were the signature weapon of the Janissaries, almost a symbol of the corps. Janissaries who guarded the palace carried long-shafted axes and halberds.

As mentioned before, these were the dogs of war; barking at the gates of Europe during the Siege of Vienna in 1529. Under the rule of one of their most successful, Suleiman the Magnificent, the unit saw its peak. Not in numbers, there were around 30,000 soldiers at that time, but in strength, loyalty, and efficiency. Even though the siege of Vienna failed, it confirmed the reputation of their engineers, sappers, and miners.

The meritocracy system within the Ottoman Empire enabled some Janissaries to gain vast wealth, influence and power. They became more and more aware of their role in the Empire. They demanded larger salaries, a greater percentage of the spoils of war and powerful positions in the government. They were also aware that they held the power to stage a military coup at any given time.

From Egypt to Hungary, they confirmed their status as an elite fighting core of the Ottoman army. Fighting in all corners of the Empire, the Janissaries were both feared and admired equally by friends and foes alike.

Almost like a social club, they permeated all structures of government, and their men were everywhere. The Janissaries were no longer obliged to celibacy, nor lived the lives of foot soldiers in the barracks, but rather purchased their own houses.

(A Janissary, a pasha -nobleman- and cannon batteries at the Siege of Esztergom, Hungary in 1543)

As an obvious consequence of their rise to power, they began adopting the characteristics of the noblemen and became ineffective in battle. In 1622, the teenage Sultan Osman II, after a defeat during a war against Poland, determined to curb Janissary excesses. He was outraged at becoming “subject to his own slaves” and tried to disband the Janissary corps blaming it for the disaster during the Polish war.

But the Janissaries beat him to it. They kidnaped the young Sultan and murdered him. This was a precedent that confirmed how dangerous the Janissaries had become. Afterwards, they held strong political positions and all bans on them were lifted. They were slaves only by name. In 1804, several Janissaries formed an illegal state in what is today known as Serbia, inciting a national uprising.

By 1826, the number of Janissaries skyrocketed to 135,000 members. Around this time Sultan Mahmud II was set to disband the unit through a series of reforms that were intended to restructure the Ottoman military in a more European fashion.

Historian Patrick Kinross suggests that Mahmud II incited the Janissaries to revolt on purpose. He describes it as the sultan’s “coup against the Janissaries,” so he could use this pretext to violently extinguish the uprising, thus ending their shadowy reign over the Ottoman Empire.