On Saturday afternoon, at the Vouliagmeni Cemetery, people who traveled from America, England, Monte Carlo, Syros, Andros, and Kasos bid farewell to Stathis Kouloukountis, a titan of the shipping industry. His death, after years of health problems, marks the end of an era for the family established by Michael Kouloukountis, as before Stathis, his other two brothers, Johnny and Elias Kouloukountis, had also passed away.

The latter was perhaps the most unpredictable scion of the shipping dynasty, to his father a “black sheep” who clashed with him from his teenage years. Unpredictable because in his autobiography “Inaccessible Shores,” published in 2017, he unfolded with unique sincerity the secrets of a great shipping dynasty. Without caring about the noise he caused, he delved deep and wrote about the competitive relationships of the Kouloukountis brothers, his mother’s mental illness, and Johnny’s suicide, which shook the family to its core.

(Elias Kouloukountis: The shipowner who sailed uncharted shores, writing fearlessly yet passionately about his family, their passions, conflicts, fights, and the tragedies that befell them)

Uncompromising, bold, and a rebel with a cause are terms that would suit Carlos Mavroleon rather than a Greek shipowner bearing the surname Kouloukountis. Yet, Elias Kouloukountis, who passed away in the summer of 2020, embodied all these qualities, perhaps even more, as one discovers reading “Inaccessible Shores.” His brother Stathis followed him almost four years later, after years of health problems, especially with his heart.

He had left London, where he had lived with his family for almost 50 years, and settled in Syros, the island he and his brother Elias adored. The shipowner who sailed uncharted shores, writing fearlessly yet passionately about his family, their passions, conflicts, fights, and the tragedies that befell them.

Memories Come Flooding Back

Known for the secrecy that has distinguished them for decades, the Greek shipowners have never desired any publicity for their professional or family secrets. That’s why Elias Kouloukountis might appear as a “defector” who refused to uphold the dynasty of Kouloukountis, writing about the very well-hidden events of his family.

(Stathis Kouloukountis: His death after years of health problems marks the end of an era for the shipping dynasty established by Michael Kouloukountis, as before him, his other two brothers, Johnny and Elias, had already passed away)

The authoritarian father Michalis Kouloukountis and the continuous quarrels, his fragile mother who was admitted to a psychiatric hospital, his brother Johnny who committed suicide, Stathis, his two marriages, his shipping ventures, the chic parties in 5th Avenue palaces, are not merely passing through the pages of the book. They are presented in a dimension that someone rarely has the opportunity to explore, from a person who for many years was considered the “black sheep” of a powerful shipping family. The phrase by André Malraux quoted in the book’s introduction partially prepares you for what is to come:

“Inheritance is not handed over. It must be conquered,” writes the author, a shipowner himself, who before “Inaccessible Shores” had published two other books on entirely different subjects. “My parents were Greek shipowners,” he emphasizes in the second paragraph, and continues: “Our house was near a golf course, and many years later, when I was preparing to sell it after my parents’ death, a friend who was helping me said, ‘Now I understand what this house is like. It’s like an ocean liner.'”

After a reference to his classmates from affluent families, whose fathers went to work by train, Elias Kouloukountis starts revealing family secrets: “My father didn’t go to work by train, but drove his own car, a Cadillac, to his office at the southern end of Manhattan. My mother stayed at home, so in a way, she was a housewife like the others, but with the difference that she had a team of servants at her disposal. Surrounded by this retinue, I unconsciously acquired the mentality of a member of a wealthy family. My father never openly said it, but the message was clear – we did not belong to the middle class.”

Although born in London, the first language spoken by the uncompromising shipowner was Greek, and in the second chapter, he reveals the first secrets regarding his parents’ marriage: “I was less than one and a half years old when my mother took me to her hometown, Syros, where we lived with her father in the large house he had built outside Hermoupolis, while my own father remained in London. The official reason for the trip was that my mother wanted to show me to her father, but the visit lasted almost two years.”

Electroshock therapy and the rebellious spirit

Nitsa may have married Michalis Kouloukountis, but “years later, in Ry, once when we were alone at the table after dinner, she told me that before she got engaged, my father had loved another man.” His mother becomes pregnant again, and as he recalls in the book, “my brother Stathis was born five years after me and was baptized in our house on November 8, 1942, on the day of the Archangels, our father’s feast day.”

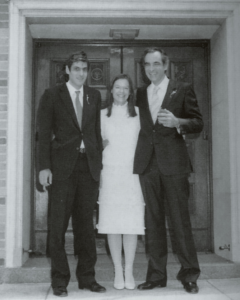

(Nitsa Kouloukounti with Elias on the left and Stathis on the right, in Havana)

The two brothers grow up with governesses and are still children when in 1946 their mother falls ill and for the next four years is admitted to a psychiatric clinic. There, she likely undergoes electroshock therapy without anesthesia, as the shipowner writes, and for a while, the father, Michael Kouloukountis, “seemed to seek solace in the company of his children. However, he soon lost interest.”

Entering adolescence, Elias studies at Phillips Exeter Academy, and in his final year, he is invited to speak at the Graduation Day ceremony in front of 1,100 people, with his parents and Stathis present at the ceremony. On that day, the conflict with his father reaches its peak when Michael Kouloukountis hears his successor saying, among other things: “When a young person fails to earn the recognition of his parents, he seeks it elsewhere,” and “the essence is that you don’t love us as individuals. You love us because we are your children.”

Apart from their parents and siblings, the explosive speech of young Elias was witnessed by his father’s two brothers, who further fueled the fire by saying, “Your son really nailed you.” Indeed, as the author disarmingly points out, the “congratulations” in a shipping dynasty are rare, and “none of the Kouloukountis siblings had heard such a phrase during their childhood. Five siblings in a Greek shipping family would hardly feel affection and support for each other.”

The party of the Goulandris family and Onassis

Shortly after the famous ceremony, his father, who punished Stathis and Johnny, erupts when the eldest tries to protect them and tells him in a “harsh, hoarse voice: ‘If you don’t like it here, find somewhere else to stay’.” “In essence, he was the sultan, an absolute ruler. Ideas like freedom of speech had no value to him,” writes Kouloukountis, who in the summer of 1954 discovers how wealthy relatives he has on a family trip to England. “The sudden wealth left me speechless. There was neither much alcohol nor much conversation at the parties we attended, but abundant food. The amount of even one buffet could feed the entire population of Somalia to the point of bursting.”

In London he will have his first sexual intercourse, at the age of 16, with a prostitute, after a walk with his cousin Eddie in the then rather infamous Soho. When he enters Harvard to study, he discovers wine: “I bought a case of Rhine wines and carried it on my shoulder like a porter all the way to the dormitory. I opened a bottle and drank it. Then I opened another and drank that too, then another and so on all night. The next morning when I urgently needed natural juice, the only thing in the fridge was wine.”

Now a charming student, he receives an invitation to a party from Vassilis and Eliza Goulandris, friends of his parents, which was given in honor of their niece Efi, in their Manhattan apartment: “Girls with inflatable dressed and boys in tuxedos entered the elevator that was all paneled and went up to the Goulandris floor, where the butler would open the door for them, a maid would take their coats and lead them to the anteroom of the ballroom, where the view of Central Park from above took their breath away.

The engagement

There was a live orchestra for the dance, the luxury Ilias Kouloukountis already knew from Greek parties, and a table full of Greeks around the library, on the other side of the room, wearing sunglasses, playing cards and smoking cigars: “A fat man an older man was sitting with the Goulandris couple and smoking his cigar. He didn’t dance with Efi once and didn’t speak to her all night. However, during that same evening, Mrs. Goulandris announced Efi’s engagement to the fat man. Even my American friends were stunned. Before our very eyes, the beautiful Efi had been sold to a bald and elderly acquaintance of her aunt’s.”

Elias Kouloukountis writes raw what he feels in every paragraph of his book, describing unknown stories with mythical names of the area in main roles. One of them stars him and the mythical Smyrna Aristotle Onassis, who held him in his arms many times when he was a child, since he was his father’s friend:

“My father and Onassis used to sit until late in the Russian Tea Room – room of the St. Moritz- where a beautiful singer from Argentina was performing and one night, according to my father, Onassis came home without his underpants.

“Elias! Elias!” I heard a voice behind me in St. Moritz, on December 6, 1968. I’m going back and who should I see? Onassis. I was surprised and said to him in Greek: “Hello, what are you doing?”.

And then another surprise awaited me. Onassis didn’t say anything, he made a sharp turn and like the ghost of Hamlet’s father, he walked away.”

(On the left, the couple Elias and Lucy on their wedding day with their best man Johnny on the right)

When Kouloukountis asked his mother why the Greek tycoon left so abruptly, he received the answer: “He knew you since you were a child and you treated him arrogantly. You spoke to him in the plural form and that sounds so cold in Greek…”. In 1968, his brother Stathis is a 26-year-old young man who has studied economics at the University of Pennsylvania and then joins the family business R&K (Rethymnis and Kouloukountis), leaving America for the usually dull London. There he will thrive and live for five decades with the love of his life, Koula, who will give him two children, Marianna and Michalis, while a stepson, Alexandros, will enter his life. Elias, on the other hand, went against everything.

Happiness and tragedies

His older brother Stathis tried in a book to encapsulate the memories and paradoxes of a shipping dynasty like the Kouloukountis based on his own experiences. Through the chapters, boring dinners with relatives in Athens parade, his visit to Mount Athos, and the Alfa Romeo, a gift from his father for his Harvard degree, a car that troubled him for years. He describes the work in the family shipping company, but also his resignation after a terrible fight with his father when he showed up at work without a suit, something unacceptable for someone working in shipping: “I announced first to my father, who was in his office with his brothers Giorgos and Nikos, and then to my cousin Michalis, the head of the office by name, that I stop benefiting from the unique opportunity given to me to come to the office and do nothing”.

For a minute or two no one speaks. “Suddenly, my father raised his voice in front of Uncle Giorgos and Uncle Nikos.

“It’s time to face reality!”

“And what is reality?” I threw at him.

“This is,” he replied, pointing to a pile of papers on his desk, to get the reaction of the firstborn in three words: “Not for me”.”

(Michael Kouloukountis with his two sons in the garden in Ry)

(Elias Kouloukountis with his uncle Manolis in New York)

His younger brother served as the best man at his wedding to Lucy, shortly before tragically taking his own life by jumping from his balcony, unable to bear the separation and divorce from his wife.

Traveling from London and New York to Monte Carlo and Singapore, Elias Kouloukountis was fortunate to meet and get to know legendary figures of Greek shipping up close. He experienced the loss of Lucy to cancer, who passed away on New Year’s Day in 1990, and eventually worked for the Kouloukountis family before the time came for him to spread his own wings. Then he heard his father call him Judas, and as he wrote poignantly towards the end of his captivating work: “All my life I searched for my father, and when I finally found him, that father was me”…