In June 2016, The War Zone’s own Tyler Rogoway wrote an extensive and thought-provoking analysis of why the U.S. Air Force either had yet to show off a fleet of advanced, combat-capable unmanned combat air vehicles (UCAV), or didn’t have any at all. It’s a long but worthwhile read, especially since the service has just announced a massive and shadowy drone-related contract for work out in the Nevada desert.

On April 6, 2017, as part of the Pentagon’s daily announcement of any contract awards worth over $7 million, the Air Force revealed a deal with URS Federal Services, Inc. for nearly two decades of work regarding unmanned aircraft. The official details are unusual, so feel free to read them yourself:

URS Federal Services, Inc., Germantown, Maryland, has been awarded an estimated $3,600,000,000 indefinite-delivery/ indefinite-quantity contract with award fee and award term portions for remotely piloted aircraft services. Contractor will provide testing, tactics development, advanced training, Joint and Air Force urgent operational need missions. Work will be performed at Nevada Test and Training Range, Nevada; Creech Air Force Base, Nevada; and Tonopah Test Range Airfield, Nevada, and is expected to be complete by March 31, 2034. This award is the result of a competitive acquisition with four offers received. Fiscal 2017 operations and maintenance funds in the amount of $2,875,894 are being obligated at the time of award. Air Force Test Center, Hill Air Force Base, Utah, is the contracting activity. (FA8240-17-D-4651).

There’s a lot to unpack here, so let’s start right at the top. This contract with URS Federal Services is worth $3.6 billion, but the program, whatever it is, isn’t expected to end until the spring of 2034. That’s 17 years for those keeping score. The math works out to more than $210 million per year, on average, over that period or $17.5 million every month.

That’s a big price tag for services. In 2013, the RAND Corporation estimated that it cost $435 million a year for the Air Force’s 20th Fighter Wing at Shaw Air Force Base in South Carolina to operate three squadrons of F-16C/D Vipers. This calculation included everything associated with flying the fighter jets, such as pay checks for military personnel and supporting contractors, fuel, depot-level repairs, as well as indirect support from the Wing’s other elements, including security forces guarding the flight line, civil engineers maintaining facilities, and basic utilities and supplies, such as electricity in the barracks and food in the chow halls. A similar analysis of the 187th Fighter Wing, a unit in the Alabama Air National Guard with just one squadron of Vipers, produced a final price tag of just $63.6 million.

In short, the URS Federal Services’ contract could potentially cover the full costs of running multiple squadrons of pilotless planes for nearly two decades. And remember that this deal likely only pays for just a portion of the total cost of this project. So, while we don’t know what unmanned aircraft—singular or plural—the Maryland-based company will be helping test, the money involved here suggests there are quite a few of them. Of course, none of this is surprising. The Air Force and defense contractors both repeated hint at the existence of multiple top secret “black” military air and space projects.

“We’re modernizing the Air Force, so you’ll see in the future new aircraft here on the ramps,” then Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter said during a visit to Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada in September 2016. “Then there are other things you also won’t see, because we like to have some surprises, also, for potential adversaries.”

These comments were squarely in line with the Pentagon’s much-touted Third Offset Strategy, a high-technology master plan to push development of revolutionary weapons and associated systems to counter rapidly modernizing near peers. On top of that, the idea has been to produce solutions to future threats that don’t necessarily require a lot of manpower or developmental funding.

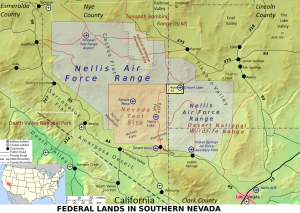

But that 2016 trip to Nellis that seems especially relevant to this new arrangement with URS Federal Services. See, all of the sites mentioned in the contract announcement fall within or along the border of the base’s extended boundaries. The first of these, the Nevada Test and Training Range (NTTR), is a massive 4,500 square mile practice space with 5,000 square miles of restricted airspace for military exercise. The area hosts the Air Force’s biggest annual mock combat events, including Red Flag. Inside the zone, fighters and attack aircraft can fire missiles, drop bombs, fly mock dogfights, and tackle surface-to-air missile threats among various other scenarios. Creech Air Force Base, the Air Force’s central hub for Predator, Reaper, and Sentinel operations, sits along the southern reaches of the NTTR, which is collocated with the National Test Site.

And then there’s the matter of Tonopah Test Range and its associated airport. Regular readers of The War Zone are surely familiar with the Nevada test site’s history. Air Combat Command, the Air Force’s top warfighting command, owns the complex, but Sandia National Laboratory—which has the primary job of designing parts for nuclear weapons—technically administers the site. This obtuse arrangement and remote location make it a perfect place to test whole squadrons of shadowy aircraft and it has done so marvelously in the past.

From 1984 until 1992, the base hosted the Air Force’s first operational stealth jets, Lockheed’s F-117. Officially, the 4450th Tactical Group was situated at Nellis. The cover story was that the unit was flying A-7D Corsair II attack planes to test new tactics and equipment – sound familiar?

In 2008, the Air Force officially retired the F-117s for good. However, the service kept a number of aircraft in so-called “Type 1000” storage at Tonopah, meaning crews had to keep them just serviceable enough to return to action in a relatively short period of time. For years afterward, there were numerous reports, along with photos and videos, indicating that at least a few of the jets were still actively flying, possibly for experimental purposes.

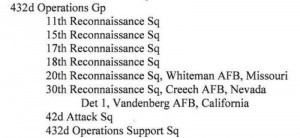

As the stealth jets moved into storage, Tonopah became home to Lockheed’s secretive RQ-170 Sentinel. The 30th Reconnaissance Squadron had at approximately 20 of the bat-wing unmanned spy planes sitting at the desert airport until 2011. Then it moved to the Air Force’s main drone hub at Creech Air Force Base and set up a separate detachment at Vandenberg Air Force Base in neighboring California.

It is very possible that some sort of Sentinel operations still occur at Tonopah as well, but clearly it is the USAF’s chosen home for secretive aircraft that have moved from the developmental stages to an early operational one. Eventually, once the programs are declassified, the programs move to a more convenient home. In the F-117’s case, that was Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico. For the RQ-170, it’s Creech and Vandenberg.

Who’s running the program URS Federal Services will be supporting isn’t entirely clear, either. The Pentagon press release points to a confusing collection of units and bases. It says the Air Force Test Center (AFTC) awarded the contract, but adds that the specific contracting office was at Hill Air Force Base in Utah. AFTC’s headquarters is at Edwards Air Force Base in California and its website doesn’t mention a detachment at Hill, but it does has a strong connection to secretive aircraft projects and a long-standing relationship with Lockheed’s famous Skunk Works design group.

Since the April 2017 contract announcement specifically cites “joint” requirements, other services or the U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM) could be involved in the project. In its budget request for the 2016 fiscal year, SOCOM asked for approximately $20 million for a hangar at a classified location somewhere in the contiguous United States, which would be large enough to conceal multiple drones. Based on the type of facilities the line items described, the Air Force Special Operations Command seemed to want the structure for an unspecified test project.

John Pike, director of the defense and security information website GlobalSecurity.org, agreed at the time that Tonopah was one possible location for the new, 36,000 square feet building. In addition, this budget proposal for the classified hangar came after work had already started on another massive hangar at the secretive Groom Lake test site, better known as Area 51, suggesting the two buildings were separate projects.

It may turn out that the Air Force moved the bulk of the RQ-170s out of Tonopah to make room for another top secret, joint drone program. We have seen official details and other hints about various secretive Air Force aircraft projects since the Sentinels came into the light.

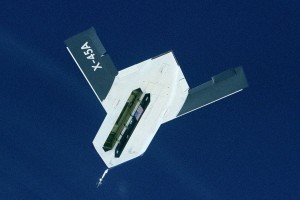

In December 2013, veteran Aviation Week reporters Bill Sweetman and Amy Butler reported the existence of another flying-wing stealth drone, dubbed the RQ-180. Six months later, Air Force Lieutenant General Robert Otto, the Deputy Chief of Staff for Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance, made the unprecedented move to acknowledge the program publicly during a speech sponsored by the Air Force Association’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies. It took the service three years to cop to the existence of the Sentinel on the record.

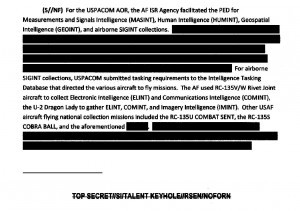

In 2014, mysterious triangular planes appeared over Texas and Kansas. The next year, an Air Force report War Is Boring first obtained via the Freedom of Information Act suggested a still-unknown spy plane had already flown missions over the Pacific region two years earlier. You can read the relevant except above.

Still, the details we know of URS Federal Services’ contract point to work on an entire operational concept based around something more like a more numerous UCAV fleet than a handful of “silver bullet” pilotless spy aircraft and suggests that these aircraft already exist. There’s no indication of weapon system research and development or procurement money involved in this “services” contract. The Air Force pulled almost $3 million out of a so-called “operations and maintenance” account (funds services generally set aside for things like payroll) to get URS Federal Services quickly off to work.

Publicly, the Air Force has stutter-started and then canceled a number of such projects since the late 1990s as Rogoway’s piece details. Before dropping out in 2006, the Air Force had tested experimental armed unmanned aerial vehicles in partnership with the U.S. Navy under the Joint Unmanned Combat Air Systems (J-UCAS) program. Six years later, the Air Force curiously shuttered another next-generation unmanned aircraft project, which it referred to as MQ-X, ostensibly aimed at producing a pilotless attacker. In the meantime, in response to Navy requirements, Northrop Grumman has built the revolutionary X-47B and proposed an improved X-47C variant, Boeing has flown a derivative of the X-45C—the last of the J-UCAS aircraft—called Phantom Ray, and Lockheed has shown artwork of an enlarged RQ-170 it calls Sea Ghost.

All of this would seem to offer more hints of a “pocket UCAV force” like the one Rogoway posited in his earlier analysis.

“You have to imagine that if there has been such an amazing outburst of programmatic creativity in the unclassified world, that there would have been at least as much friskiness on the classified side of the house,” Pike told me back in 2015, referring to years with a nearly endless stream of public drone prototypes and concepts.

While there are just too many unknowns to be sure, given the history of the locations, the money involved, the time frame, and what we already know about separate developments, this contract suggests the Air Force is up to something big out in Nevada. We’ve already put in a Freedom of Information Act Request for documents related to the contract and we’ll be sure to follow up with any new details as we become aware of them.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions