Look up on any clear night and you can see myriad stars, planets, and the Milky Way stretching across the sky. The chances are that you know some of the constellations. The International Astronomical Union recognizes 88 constellations, ranging from the giant water-serpent Hydra to tiny Crux (the Southern Cross).

These are largely based on the mythology of the ancient Greeks. But they share remarkable similarities with the constellations of the oldest living cultures on the planet.

Hunters and sisters

One of the most easily recognizable constellations is Orion. In Greek mythology, the boastful hunter was killed by a giant scorpion.

(Orion dominates the evening skies during summer in the Southern Hemisphere and appears upside-down to us in Australia. Photo: Stellarium)

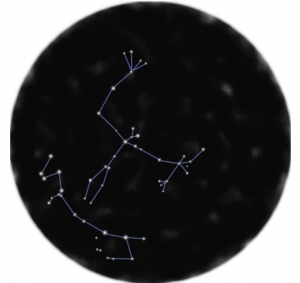

Orion is constantly pursuing the seven sisters of the Pleiades. In the sky, Orion is defending himself from the charging bull Taurus, represented by the V-shaped Hyades star cluster. The Hyades are daughters of Atlas and sisters of the Pleiades.

(Orion -right- fights Taurus the bull -middle- while pursuing the seven sisters of the Pleiades -left-, as seen from Australia. Photo: Stellarium)

In Wiradjuri Aboriginal traditions of central New South Wales, Baiame is the creation ancestor, seen in the sky as Orion – nearly identical in shape to his Greek counterpart. Baiame trips and falls over the horizon as the constellation sets, which is why he appears upside down.

(The stars of Orion also form a man, Baiame, In Wiradjuri traditions. Photo: Stellarium, Wiradjuri artist Scott ‘Sauce’ Towney)

The Pleiades are called Mulayndynang in Wiradjuri, representing seven sisters being pursued by the stars of Orion.

(The Pleiades are seven sisters in Wiradjuri traditions, called Mulayndynang. Photo: Stellarium, Wiradjuri artist Scott ‘Sauce’ Towney)

In Aboriginal traditions of the Great Victoria Desert, Orion is also a hunter, Nyeeruna. He is pursuing the Yugarilya sisters of the Pleiades but is prevented from reaching them by their eldest sister, Kambugudha (the Hyades).

The International Astronomical Union recognises 88 constellations … largely based on the mythology of the ancient Greeks.

Scorpions and canoes

In Greek mythology, the scorpion that killed Orion sits opposite the hunter in the night sky as the constellation Scorpius. They were placed on opposite sides of the sky by the gods to keep them away from one other.

(The Greek constellation of Scorpius as seen from Australia, which dominates the winter skies of the Southern Hemisphere. Photo: Stellarium)

A comparable relationship can be found in the traditions of the Torres Strait Islanders. The culture hero, Tagai, killed his 12-man fishing crew (Zugubals) in a rage for breaking traditional law, before they all ascended into the sky.

Tagai is standing on his canoe, formed by the stars of Scorpius. The Zugubals are represented by two groups of six stars: the belt/scabbard stars of Orion (Seg) and the Pleiades (Usiam). Tagai placed the Zugubals on the opposite side of the sky to keep them far away from him.

(The constellation Tagai. The curve of stars towards the bottom left are the stars of Scorpius. Photo: Wikimedia/Osiris, CC BY-SA)

The twins

Another famous constellation is Gemini, the twins, denoted by the bright stars Castor and Pollux.

(Gemini’s two bright stars Castor and Pollux, as seen from Australia. Photo: Stellarium)

Many Aboriginal groups also view these stars as brothers. In the Wergaia traditions of western Victoria, they are the brothers Yuree and Wanjel, hunters who pursue and kill the kangaroo Purra.

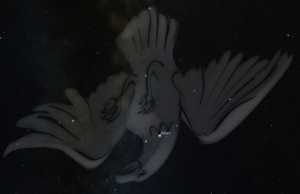

(In Wergaia traditions the brothers take the form of animals: Yurree -Castor-, the fan-tailed cuckoo, and Wanjel -Pollux-, the long-necked tortoise. Photo: Stellarium, John Morieson and Alex Cherney)

In eastern Tasmania, the constellation Gemini represents two ancestor men who created fire, walking on the road of the Milky Way – similar in orientation to the Greek constellation.

Bird flying high

Bordering the zodiac near Sagittarius lies the constellation Aquila, the eagle. In Greek mythology, Aquila carried the thunderbolts of Zeus.

(Aquila, the eagle, in Greek mythology. Photo: Stellarium)

In Wiradjuri traditions, Aquila is Maliyan, the Wedge-tailed Eagle. In some Greek and Wiradjuri traditions, the star Altair is the eagle’s eye – despite being seen in different orientations.

(Maliyan, the Wedge-tailed Eagle in Wiradjuri traditions. Photo: Stellarium, Wiraduri artist Scott ‘Sauce’ Towney)

Even Indigenous constellations around the world have noteworthy similarities.

The Emu in the Sky, seen by Aboriginal groups across Australia, is composed of the dark spaces in the Milky Way.

The rising of the celestial emu at dusk informs observers about the bird’s breeding behaviour. Across the Pacific, the Indigenous Tupi people of Brazil see the same shape as a rhea, a large, flightless bird that is native to South America and related to the emu.

The rhea’s behaviour is nearly identical to that of the emu and the Tupi and Aboriginal traditions are remarkably similar.

Why the similar stories?

We’ve learned a bit about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander views of the stars.

What we don’t yet know is why different cultures have such similar views about constellations. Does it relate to particular ways we humans perceive the world around us? Is it due to our similar origins? Or is it something else?

The quest for answers continues.

The author would like to acknowledge and pay respect to Wiradjuri, Meriam Mir, Wergaia, and Aboriginal Tasmanian artists and elders for sharing their knowledge of the stars.

* This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article online at theconversation.com

** Duane W. Hamacher is Senior ARC Discovery Early Career Research Fellow at Monash University.

Source: neoskosmos

Ask me anything

Explore related questions