In an extensive piece titled “Poor Greece splurges on costly drugs, to Brussels’s annoyance”, author Carmen Paun explains how the debt-stricken country has been squandering large sums of money on extremely expensive drugs despite the EU’s pressure to turn to more affordable drugs -so called generics- in an effort to cut costs. From Politico.eu:

Greece is addicted to expensive medicines, and three rounds of rehab have made only a small dent.

It’s a hard habit to kick: Greece for years lavished unusually high sums on the newest, most expensive drugs on the market. That led the European Commission to zero in on this, saying Athens would have to spend smarter to help cut its budget deficit. In the third bailout agreement between the European Commission and Greece, Brussels called on the Greek government to ensure that 60 percent of medicines are cheaper, copycat versions — so-called generics — by March 2018.

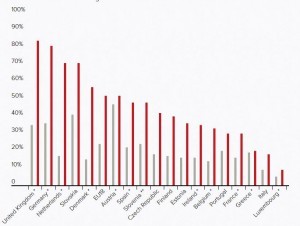

Only a quarter of medicines prescribed in Greece are generics, according to the European Commission, putting Greece at the bottom of the charts, ahead of Italy and Luxembourg but behind countries like Germany and the Netherlands, which have penetration rates of 81 percent and 71 percent for generics, respectively.

To usher the reforms through, the Greek government needs to face down opposition from powerful vested interests: pharmacies that make a killing from selling the more expensive original drugs and many specialist doctors who receive incentives from drugmakers to prescribe the latest name-brand medicines.

“Nobody else has ever implemented such heavy health care reforms in such a short amount of time,” said Nikos Maniadakis, a professor at the National School of Public Health in Greece.

Athens will have to overcome resistance to reform from its domestic drugmakers and, perhaps most sensitive of all, a deep suspicion among Greek patients that generics are simply inferior.

“Greeks consider generics a second-class medicine due to a law in 2012 that said the poor people get generics,” said Pascal Apostolides, president of the Hellenic Association of Pharmaceutical Companies (SFEE), which represents multinational drugmakers in Greece.

The country has been making some slow progress in response to the pressure from Brussels. Generics penetration has risen 10 percentage points since 2010 and the Commission broadly argues that it is “proud of the progress” in the Greek health care sector.

In need of reform

In 2010, when the financial crisis hit, Greece’s medical system was already idiosyncratic and dysfunctional.

On the one hand, it had the highest number of doctors per capita in the EU and pharmacies at every street corner. But the system was hardly functioning well: Patients paid almost 40 percent of health care costs from their own pockets.

These costs were a debilitating weakness from both an economic and humanitarian perspective. When Greeks lost their jobs and subsequently their health insurance, many couldn’t afford life-saving medication.

Martha Frangiadakis, a volunteer at a free clinic in Athens, where doctors and pharmacists volunteer and which runs on in-kind donations, gave a stark example of the personal sacrifices that were commonplace at the height of the crisis. She described how one man came to ask for Glivec, a cancer drug that costs €3,000 per course, that he could no longer afford. The clinic put out a call and another man suffering from cancer offered to share some of his own medication. That was the only way some people could survive.

The left-wing Syriza government tried to combat these problems by passing a law last year to give health care access to those who had no insurance, but the move piled more pressure on the health system. The extra strain meant some method to contain drug costs became more vital than ever.

As Greece looks toward its exit from EU oversight next year, when the third — and many hope final — bailout agreement ends, Athens still has a lot of work to do to ensure its health system stands on its feet.

Pharmacies and doctors in the crosshairs

Greece will need far more aggressive surveillance of its pharmacies and doctors if it wants to whittle the costs down and accelerate the transition to generics.

Greece’s tightly regulated pharmacies were quickly identified as a problem in the early days of the crisis, because they were widely accused of being wedded to expensive drug brands. In the first bailout agreement, the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund asked the Greek government to remove restrictions on who can open a pharmacy to create more competition. The troika also wanted Greece to introduce an electronic system to monitor doctors’ prescriptions to increase the uptake of generics.

Seven years later, many of these demands have been met on paper, but are failing to make much difference in practice.

More at politico.eu

Ask me anything

Explore related questions