Six months after Turkey declared a state of emergency there is great concern for the independence of its justice system and the rule of law. Nevertheless, there are signs of hope. Ulrich von Schwerin reports from Ankara.

Tens of thousands of people are in Turkish prisons awaiting trial. Most are soldiers, police officers, judges and administrators, but teachers, docents and journalists are among them as well. They are all accused of belonging to the so-called “Gulen movement,” named after the Islamic preacher Fethullah Gulen. He has been living in self-imposed exile in the United States for more than 17 years, and is the man that Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan says is responsible for last year’s failed military coup in his country. Very few of those incarcerated have been formally charged with a crime, and most cases are still pending. Fewer still expect to receive a fair trial.

Six months after the implementation of a state of emergency following the July 15 coup attempt, many lawyers and opposition politicians say the Turkish justice system is in dire straits. Some 4,000 judges and state prosecutors were fired in the wake of the failed overthrow, accused of being Gulen supporters: 3,000 are currently in jail. In order to fill the gaps left by these mass firings, quick confirmations have taken place to appoint student teachers as judges. Legal representatives say that those teachers’ lack of essential training and experience has overtaxed many of them.

Grievances struck down, complaints ignored

Beyond the firing of judges and prosecutors, many here are concerned about a number of decrees tied to the state of emergency. These have allowed many changes to the legal process. Although there are serious doubts about the legality of these decrees, the constitutional court has refused to address the issue, says Ozturk Turkdogan, president of the Human Rights Association (IHD) NGO. The European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg is also of little help in this instance, due to its long backlog of pending cases.

“As a lawyer, there is little I can do about these abuses, because the justice system is broken. There is no rule of law at the moment. I could walk out of here and be arrested,” said Turkdogan while meeting with a delegation of the German Bar Association (DAV).

The delegation traveled to Ankara to get an impression of the situation that Turkish colleagues are facing under the state of emergency. Turkdogan says that judges live in constant fear of being fired, critical lawyers are being threatened and that the rule of law no longer applies.

Separation of powers watered down

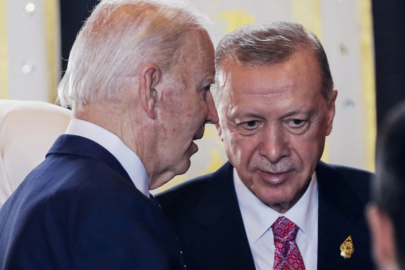

The constitutional reforms being pushed by President Erdogan, which were approved by Turkey’s parliament last week and are to be voted on by citizens in a referendum in early April, will further limit the independence of the justice system. In the system being pursued by Erdogan, the president will not only have the power to appoint most of the country’s constitutional judges, he will also control the appointment of state prosecutors and lower-court judges. With that, the separation of powers so essential for a true democracy will be greatly diluted.

Read the rest of the article here: DW.com