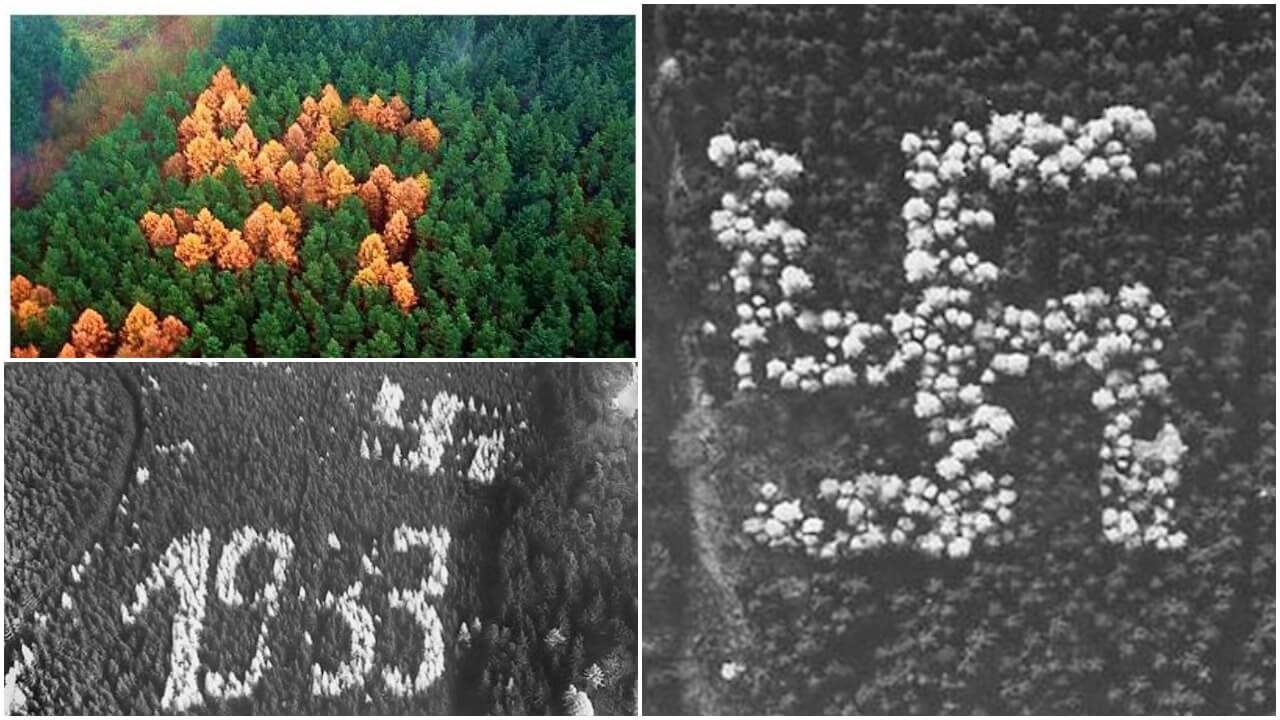

It’s in the human nature to seek logic in everything, but when a giant group of larches bloomed in a pine forest forming a swastika sign, it’s hard to find any logical sense. Outside of the northeast German town, Zernikov, a patch of larch trees cover 4,300 sq yds of the pine forest, carefully arranged to look like a swastika sign.

For a few weeks every year in the autumn and in the spring, the colour of the larch leaves would change, contrasting with the deep green of the pine forest. The short duration of the effect, combined with the fact that the image could only be discerned from the air and the relative scarcity of privately owned airplanes in the area, meant that the swastika went largely unnoticed after the fall of the Nazi Party.

During the subsequent Communist period, Soviet authorities reportedly knew of its existence but made no effort to remove it. However, in 1992, the reunified German government ordered aerial surveys of all state-owned land. The photographs were examined by forestry students, who immediately noticed the design.

Local forester Klaus Göricke measured the trees themselves and determined that they were in fact planted in the late 1930s, as Hitler was coming to power. Which means every autumn the swastika sign bloomed in the forest and disappeared in spring and summer, for years, without being discovered.

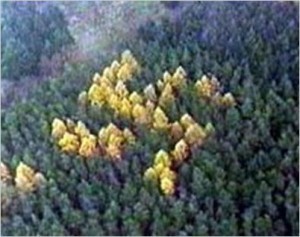

In the late 1970s, American troops discovered a swastika along with the numbers “1933” planted in a swastika style in a forest in Hesse. Who planted the trees is unknown.

Action to were immediate. In 1995, forestry workers armed with chainsaws made their way to the copse of larches and cut down 40 trees. They reported back to their supervisors that the symbol was now unrecognizable, and the commotion surrounding the Kutzerower Heath quickly subsided.

But the forestry workers were badly mistaken. It took five years before their error was discovered, but in 2000, the news agency Reuters published photos of a bright yellow and clearly visible swastika in the forest near Zernikow — even if the edges were a bit frayed. And the media response was once again immense. Even the Chicago Tribune wrote about it, noting that the swastika forest was not helpful for a region that had already become notorious for racist violence.

In fact, officials started becoming increasingly worried that the place could become a pilgrimage site for neo-Nazis. This prompted the Agriculture Ministry of the eastern state of Brandenburg to plan drastic measures. In 2000, Jens-Uwe Schade, a ministry spokesman, told Reuters that the intention had been to cut down all the trees in the area. But the BVVG, the federal office in charge of property management, blocked the plan because ownership of some of the property was in dispute and only gave the green light for state forestry officials to cut down 25 of the trees.

This was done on the morning of Dec. 4, 2000. Forestry workers had to be very careful about choosing which trees to cut down and about making sure that the swastika was no longer visible. They also had to cut the stumps just a few centimetres above the ground so that they could no longer be viewed from the air.

Although, the prominent swastika in the Uckermark region pictured above was eventually cut down in 2000. The Brandenburg state authorities, concerned about damage to the region’s image and the possibility that the area would become a pilgrimage site for Nazi supporters, attempted to destroy the design by removing 43 of the 100 larch trees in 1995.

However, the figure remained discernible with the remaining 57 trees as well as some trees which had regrown, and in 2000 German tabloids published further aerial photographs showing the prominence of the swastika. By this time, ownership of around half the land on which the trees sat had been sold into private hands, but permission was gained to fell a further 25 trees on the government-owned area on December 1, 2000, and the image was largely obscured.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions