Turkey’s referendum was run on a promise of economic renewal. The powerhouses of the $857 billion economy didn’t buy into that pledge. In major industrial centers, voters largely rejected a proposal to grant President Recep Tayyip Erdogan unfettered powers.

Here’s how the data break down.

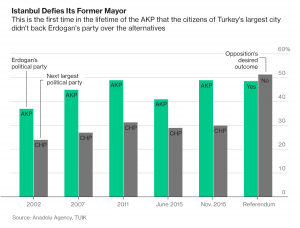

1. While the preliminary tally points to a 51.4 percent nationwide win for the constitutional changes, that was almost precisely the inverse of how people voted in both the capital city, Ankara, and the commercial capital, Istanbul.

2. In Izmir, the next most populous metropolis, less than a third of three million voters endorsed the proposal. That’s not such a surprise in what’s traditionally been an opposition stronghold, but Istanbul — Europe’s largest city, with an economy bigger than Portugal or Peru’s — does not have a history of defying the president’s wishes.

While the lead for “No” was slim, this referendum represents the first time since Erdogan founded the AK Party in 2001 that Istanbul’s citizens didn’t back their former mayor.

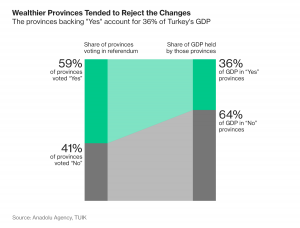

3. That pattern holds true across the country overall, where richer regions were less likely to endorse the government’s plan. Only 33 of Turkey’s 81 provinces may have voted no, but they account for almost two-thirds of the country’s gross domestic product.

The average economic output per capita in “No” voting cities was 59,726 liras (or $25,600, according to conversion rates contemporaneous to the most recent regional data). In “Yes”-voting provinces, it was less than a quarter of that.

4. On the campaign trail, Erdogan promised to use his new ability to issue laws by decree in order to jump-start the economy. Still, “it’s not clear that people in rural areas studied the detail of the referendum proposals and voted accordingly; it’s fair to say that they were acting largely out of a sense of conservative identity, out of allegiance to a party that’s always acted in their interests,” said Bekir Agirdir, head of the Konda polling agency, in the wake of the result.

But “Yes” voters weren’t the only ones voting ideologically, just as a lack of economic prospects didn’t always equate to government support.

The “No” vote was strong in the Kurdish southeast, which is at the same time poorer and less enthusiastic about the government than the median Turkish voter. (That said, a greater preference for the new constitution could be observed in heavily Kurdish provinces than the same voters’ support for the government at the last election might have suggested. That’s one of the things that’s fueling opposition allegations of election fraud.)

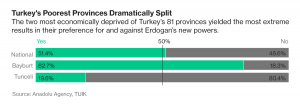

So, while most rural parts of Turkey endorsed the referendum package, it’s noteworthy that the two most economically deprived of Turkey’s 81 provinces were the most extreme ones nationwide in voting for and against Erdogan’s new powers.

The staunchly nationalistic province of Bayburt, and the Kurdish province of Tunceli — from where the leader of the opposition hails — together account for just over a thousandth of Turkey’s economic output. But they voted for and against the proposal in almost equal measure.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions