Some years ago, low on cash, I took an unusual job in Tokyo’s entertainment district Shibuya. Every morning I dressed in a swallow-tailed jacket stained with the sweat of a previous shift worker, assumed a fake name, and pretended to be an English butler for the women, and occasionally men, who visited a mock castle interior on the fifth floor of a beige high rise.

The premise was that these customers were princesses or princes who had traveled without a passport and ended up in a foreign land. Often, they were dressed the part and on arrival they were given a bell to ring for service. As a butler, my job was to take guide them into curtained-off nooks or behind trellises studded with artificial roses. There, we could flirt and swap stories, and I could earn commissions by encouraging them to order the pseudo-Italian fare and brightly colored cocktails we served up. It was one of scores of fantasy diversions scattered across the city. A couple floors down, men could pay for dates with young women in school uniforms. Elsewhere, there were fetish dungeons and, for the less adventurous, co-sleeping specialty shops that charged for cuddles by 20-minute increments.

“Yesterday the horses got away and I had to catch them,” I would hear myself telling groups at Formica tables in slowly enunciated English or rudimentary Japanese. From office workers in plastic tiaras I learned you could pick mushrooms near Kyoto; from out-of-towners claims that Nagoya had the best miso soup in Japan.

Our castle expected its guests to be one-off visitors—an assumption reflected in the overpriced food and, by Japan’s rigorous standards, sloppy service. But despite this, it hosted loyal regulars. There were middle-aged women who dressed in children’s clothing and wrote careful letters about not wanting to grow up. There was “Princess” Kanon, who came back every week to see her favorite butler and sometimes talked about having been abused; there was Mr. Six, named for the fact that he once had only six percent body fat; and there was “Prince” Shinichi, who had questions about love and once soiled himself on the castle’s parquet floor.

The butlers—none fluent Japanese speakers—were hardly qualified counselors. But the castle served an important function: it was a confessional, remote from the megalopolis below and, for some, a secret world in which to disappear.

My short stint there, and the stories the customers shared, came to mind recently, when I came across a book about Japanese people vanishing by the thousands. A French journalist called Léna Mauger had investigated the phenomenon of johatsu, or “evaporated people.” Every year, her book’s blurb claimed, nearly one hundred thousand Japanese vanish without a trace.

Many who cannot not lose the black dog of depression, throw the monkey of addiction from their backs, or buck the horns of sexual impropriety, remove themselves from their communities, Mauger said. They shed their addresses, jobs and families like unwanted costumes; sometimes they changed their names or their faces. “It’s something you can’t really talk about, but people can disappear because there’s another society underneath Japan’s society,” the author said in an interview about her book.

One story went like this: a man named Norihiro had been fired from his engineering job but was too ashamed to tell his family. Each morning, he put on his shirt and tie, kissed his wife goodbye and drove in the direction of his office. But without a place to go he stewed in his car all day, sometimes staying late to give the impression he was drinking with colleagues. Eventually, with salary no longer forthcoming, Norihiro could not continue the lie: instead he vanished, disappearing to Sanya, a place apparently so secret and shameful it had been scrubbed from Tokyo’s maps. “Taxi drivers avoid venturing into this shady neighborhood,” wrote Mauger. “The only ones who go there, they say, are those excluded from the good life and forgotten by everyone—the nameless.”

It was captivating. But early inquiries revealed that many in Japan doubted the veracity of Mauger’s reporting. “Most of us who saw [the story] found it unbelievable,” says Charles McJilton, a longtime expatriate resident of Japan, whose relief organization Second Harvest provides food assistance to other non-profits that operate in Sanya, which far from being shady has been openly written about as “Tokyo’s coolest ghetto.” Yes, its name was removed from maps in 1966 and its geographical boundaries incorporated into several other surrounding districts—but there is nothing particularly remarkable about that. Municipal authorities the world over have long bulldozed or renamed unsavory districts in a bid to boost an area’s reputation and attract new investment.

Not that much investment ever came to Sanya. The gritty neighborhood—which spans only a few blocks in each direction—had once been a refuge for down and out men seeking casual labor with no questions asked. By the time McJilton moved there in the early 1990’s, changing labor laws were already putting an end to that practice, and today the district is a place of cheap rooms and budget restaurants.

Parts of Mauger’s book are “fantasy at best,” McJilton tells TIME.

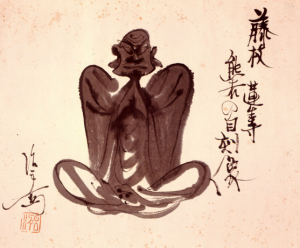

(Depiction of a Kappa, a type of vampire like lecherous creature of Japanese folklore)

‘There’s no exit, no escape’

Hidden worlds are a part of Japanese popular culture as they are anywhere. Elephants vanish and women climb down ladders into parallel realities in Haruki Murakami stories. In Mario games, the titular plumber squeezes through drainpipes into netherworlds populated by angry turtles. The country’s highest-grossing film—an animation feature about a family trapped in a supernatural world—is called Spirited Away.

“When we were children we would hear these kamikakushi stories all the time,” says Maho, an interpreter engaged by TIME, using the Japanese word for “spirited away.” She adds: “The vanished would always come back with some mark. Something to show they’d been taken.”

The fables are often surreal and grim. There’s the five-year-old who goes missing in the mountains only to return to the family home weeks later with her stomach full of tiny snails. In The Legends of Tono, anthropologist Kunio Yanagida records tales of women whisked away by wild-eyed mountain men, and of girls dragged into deep rivers by lusty imps called kappa. Their grotesque offspring are “hacked into pieces, put into small wine casks, and buried in the ground.”

A cultural prevalence of vanishing, however, is not reflected in the country’s official statistics. Japan’s National Police Agency registered around 82,000 missing persons in 2015 and noted that some 80,000 had been found by the end of the year. Only 23,000 of them had remained missing for more than a week and about 4,100 of them turned out to be dead. In Britain, which has about half the population of Japan, more than 300,000 calls were made to police in 2015 to report a missing person.

The Missing Persons Search Support Association of Japan (MPS), a non-profit set up to provide support to the families of the evaporated, argues that official numbers reflect under-reporting and are way too low. “The actual, unregistered number is estimated at several times 100,000,” claims the organization’s website.

Takehiko Kariya, professor of the sociology of Japanese Society at Oxford University’s Nissan Institute, explains that while people go missing in every country there are some factors that make the existence of johatsu more likely in Japan. For the past 20 years, he says, schools have officially nurtured creativity and individual expression but the social milieu and the workplace remain unchanged. A new graduate can find themselves in a hierarchical office environment being treated no better than a salaryman straight out of the 1980s.

Read the rest of the article HERE

Ask me anything

Explore related questions