Almost 500 years ago, Italy’s Campi Flegrei supervolcano erupted, spewing molten rock and thick plumes of smoke into the atmosphere for eight days straight, and literally forming a new mountain from the chunks of Earth it drew from below.

Now, researchers are warning that this vast, fiery cauldron could be ready to blow once more, with pressure building up over the past 67 years showing no signs of easing up. And just to put that into perspective, this supervolcano is responsible for one of the biggest eruptions on the planet.

“By studying how the ground is cracking and moving at Campi Flegrei, we think it may be approaching a critical stage where further unrest will increase the possibility of an eruption, and it’s imperative that the authorities are prepared for this,” says Christopher Kilburn from the University College London Hazard Centre.

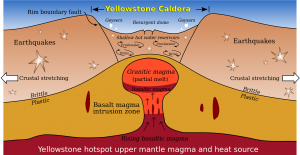

You might picture a supervolcano as just like a regular volcano, only super-sized, but it’s more like a giant volcano that’s been flattened into the ground, leaving extensive fields of volcanic activity like we now see at Yellowstone.

Supervolcanos form when a regular volcano ejects so much magma from its centre, it collapses in on itself, leaving behind a vast crater filled with geysers, swelling steam vents, and sulphuric acid.

Campi Flegrei (or “burning fields” in Italian) covers an area of 100 square kilometres (38 square miles) just west of Naples, with a massive 12-km-wide (7.4-mile) caldera at its centre. It boasts 24 craters and large volcanic edifices, mostly hidden under the Mediterranean Sea.

In recent times, Campi Flegrei has had two major eruptions – 35,000 years ago and 12,000 years ago – and a smaller eruption in 1538.

It’s all relative though, because that “smaller” eruption lasted for eight days straight, and spewed so much material into the surrounding area, it formed a whole new mountain, Monte Nuovo.

And that’s not even the half of it. When Campi Flegrei formed 200,000 years ago, it was the result of a volcanic collapse so cataclysmic, some researchers have tried to tie it to the extinction of the Neanderthals.

The eruption is thought to have spewed almost 1 trillion gallons (3.7 trillion litres) of molten rock onto the surface, along with just as much sulphur into the atmosphere, triggering what researchers now call a ‘volcanic winter’.

“These areas can give rise to the only eruptions that can have global catastrophic effects comparable to major meteorite impacts,” Giuseppe De Natale from Italy’s National Institute for Geophysics and Volcanology, told Reuters back in 2012.

Now, a team from University College London and the Vesuvius Observatory in Naples have teamed up to investigate whether Campi Flegrei could be preparing to erupt once more, and have found that the unrest that has been bubbling since the 1950s has had a dangerously cumulative effect.

The team reports that the volcano has been stirring for 67 years, with two-year periods of unrest in the 1950s, 1970s, and 1980s giving rise to small earthquakes – a pattern that was also seen in the lead-up to the 1538 eruption.

Previously, research has suggested that these periods of unrest could lead to a loss of energy required for an eruption, but this time, the researchers say that energy is doing nothing but accumulating.

“We don’t know when or if this long-term unrest will lead to an eruption, but Campi Flegrei is following a trend we’ve seen when testing our model on other volcanoes, including Rabaul in Papua New Guinea, El Hierro in the Canary Islands, and Soufriere Hills on Montserrat in the Caribbean,” says Kilburn.

“We are getting closer to forecasting eruptions at volcanoes that have been quiet for generations by using detailed physical models to understand how the preceding unrest develops.”

The research mirrors what a team led by Giovanni Chiodini from the Italian National Institute of Geophysics reported late last year, when they too modelled Campi Flegrei’s activity and found that it’s dangerously close to hitting a critical pressure point that could trigger another eruption.

Unfortunately, no one can say if or when the supereruption will actually occur, because it all depends on how magma swelling 3 km below the surface of the central caldera will behave in the coming decades.

If this magma stretches an uplifts the ground above to its breaking point, an eruption becomes more likely, but it’s anyone’s guess if that’s what’s going to occur.

But we do know that if an eruption does occur, it will affect the 360,000 people living across the caldera, and the nearly 1 million people living in Naples proper.

“Our findings show that we must be ready for a greater amount of local seismicity during another uplift, and that we must adapt our preparations for another emergency, whether or not it leads to an eruption,” says one of the team, Giuseppe De Natale, former director of the Vesuvius Observatory.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions