While most attention over the past few years has been centred on Russia’s aggression and the critical situation in the Middle East, very few analysts notice a security emergency on the EU’s south-eastern border.

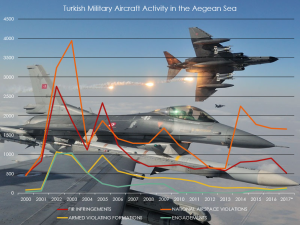

Only in 2016, the Greek General Staff recorded 1,671 national airspace violations by Turkish aircraft. The size of this breach can be easier understood if one considers that, during the same period, NATO jets scrambled to intercept Russian military planes 780 times, which is the highest recorded number since the Cold War.

The root of tensions in the Aegean is Ankara’s efforts to question the existing status quo in the area, both in the air and at sea. This antagonism has led the two countries three times (1976, 1987 and 1996) to the brink of war. According to international norms, the national airspace should correspond to territorial waters. However, Greece, since 1931, established its airspace to 10nm, while its territorial waters remain at 6nm. This international paradox was never challenged by Turkey before its invasion in Cyprus.

The reasoning behind the Turkish stance derives from its claims that the 4nm difference between Greek airspace and its territorial waters should be considered as international space over which Greece has no authority. The situation became more complex when, in 1995, the Turkish Parliament declared that any possible extension of the Greek territorial waters up to a limit of 12nm – and subsequently the national airspace – would automatically result in an act of war (casus belli).

Over the space of the past seventeen years, Turkish fighter jets – many of them equipped with combat arms – have been violating Greek airspace (see below), resulting in interception attempts by Greek forces and, in many cases, dangerous air engagements and dogfights, even over inhabited islands of the Eastern Aegean.

In reality, Turkey’s revisionism in the Aegean can be traced to its existential fear of possible geopolitical, economic and military isolation. Taking into consideration the political instability and security threats that the country is facing over the space of the past five years, one could easily understand how fragile peace on NATO’s Eastern flank is. In that frame, Erdogan’s rhetoric on possible change and renegotiation of the Lausanne Treaty – which defined, in 1923, the boundaries of the modern state of Turkey – endangers not only Greco-Turkish relations, but the entire South-East Mediterranean region.

The frequency of Turkish violations and infringements also dramatically affects and puts in harm’s way civil aviation in the area. The concentration of the Greek islands, coupled with the intensity and the heights that the warplanes can reach, increase the probability of another fatal accident in the Aegean, as has happened in the past.

Another important aspect of this secret war is the financial cost. According to Greek officials, every time a Greek fighter jet scrambles, the cost rises to €8,000 – €12,000 per hour. Of course, in the case of collision, this cost exceeds the €50,000,000 per plane without counting the loss of human lives. As it is easily understood, these numbers for a country in deep recession are onerous and deprive other sectors more vital for the daily life of the Greek citizen of important resources.

Unfortunately, during the last four decades, the EU and especially NATO, have not paid the necessary attention to Turkish bellicosity. It is evident that the Turkish political and diplomatic fluctuations should alert the West. Impartiality and apathy with regards to Turkish hostile behaviour towards its neighbours should not be the norm.

Erdogan and Putin’s recent marriage of convenience has raised many analysts’ doubt over Turkey’s intentions. Therefore, NATO should not underestimate the fact that Greece remains the oldest member of both NATO and the EU in the region, committing – even under the current horrendous financial situation – 2.38% of her GDP to defence, and thus to the Western alliance.

In fact, the Aegean dispute has not been adequately debated. It is not solely a Greco-Turkish problem. It should be perceived as an EU problem, as Greece is called upon to protect the Union’s external borders in the vital region of the Eastern Mediterranean. The EU should finally define, in the clearest terms, its current land, sea and air borders, in order to be prepared to protect them against any external threat.

An idea would be the creation of a common European airspace, by establishing territorial sea and airspace 12nm, throughout the EU. This decision might discourage further provocations and hostile acts by third countries, as well as defusing tensions between the two bitter friends in the Aegean.

author: Panos Tasiopoulos

source: martenscentre.eu

Ask me anything

Explore related questions