Ever heard someone say their family member “died of old age”?

That’s almost never what actually happened, at least from a medical perspective. Aging in and of itself is not a cause of death. When most of us say that someone died of old age, we usually mean they succumbed to an illness that a younger, healthy person would likely have survived, such as pneumonia or a heart attack.

In humans, the probability that one of these events will happen increases as we age. This is what we mean when we talk about mortality.

But not all animals get more likely to die as they get older, according to the book “Cracking the Aging Code: The New Science of Growing Old and What it Means for Staying Young,” by theoretical biologist Josh Mitteldorf and ecological philosopher Dorion Sagan. The authors write that some creatures, such as the desert tortoise, actually get less and less likely to succumb to mortality the older they get, while others enter a period of aging and then come out of it.

All of this suggests that aging is genetic, write Mitteldorf and Sagan. That means that in order to counter aging, we need to rethink how we live.

Cracking the aging code: There are no constraints

“Aging is not [always] a relentless process that leads to death,” Michael R. Rose, an evolutionary biologist at the University of California at Irvine, told Business Insider in 2015.

Indeed for some organisms, aging simply “is a transitional phase of life between being amazingly healthy and stabilizing,” Rose said. In other words, the period in which they’re most at risk of death doesn’t necessarily coincide with their later years.

Mitteldorf and Sagan emphasize this point as well, and suggest that humans may not be obligated to experience aging the way we currently do.

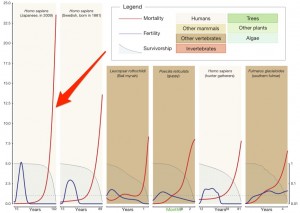

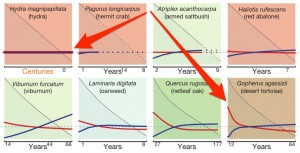

They point to a study published in the journal Nature that compares how 46 different species live and die. Some organisms, the research found, don’t age — their mortality rates stay constant from around the time they’re born until the time they die. Other creatures enter a period of aging — when they are the most likely to die — and then come out of it, continuing their lives.

Here’s a chart from that study comparing what aging looks like in a modern-day human, a human living in the 1800s, and other organisms. (Mortality rates are in red, fertility rates are in blue.)

(Click to enlarge)

See that sharp rise in the modern Japanese person’s thin red line? Humans have an incredibly long aging period.

But lots of other creatures’ life spans look nothing like this, as illustrated by the chart below. The “immortal” hydra, a tiny freshwater animal that lives to be 1,400 years old (left arrow), is just as likely to die at age 10 as it is at age 1,000.

The desert tortoise (right arrow) has a high rate of mortality in early life, but that rate actually declines as it ages. This means that the critters lucky enough to survive their early years will likely live out their remaining (healthy) years. Biology determines how many of those years they have.

If we could figure out how and why humans begin to age — something Mitteldorf and Sagan believe will require a much deeper understanding of our genetics — we might be able to change how we experience aging.

“Nature can do whatever she wishes with aging (or non-aging). Any time scale is possible, and any shape is possible,” write Mitteldorf and Sagan. “There are no constraints.”

Ask me anything

Explore related questions