“The decision is made,” reads the text Ksenia Sobchak is due to deliver on Russian TV. “Enough silence, I’ve thought about it for months… I intend to be the candidate for those who want to vote against everyone.”

The declaration of intent ends weeks of speculation as to whether the journalist, socialite, famous daughter and yet-more-famous-goddaughter would run in presidential elections next March. The talk that Ms Sobchak was considering a presidential bid — against the public advice of fellow liberal opposition politician Alexei Navalny — had electrified Russia’s somnambulant political circles. And the news that she will run will be seen as a blow to Mr Navalny’s hopes, and a split in the opposition now seems likely.

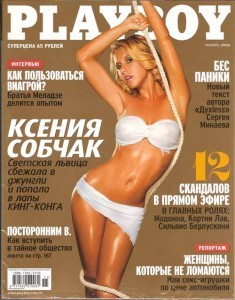

For Ms Sobchak, 35, the announcement completed a remarkable circle; the reinvention of “Russia’s Paris Hilton” as its Chelsea Clinton.

For much of her professional life, the daughter of St Petersburg’s first post-Soviet mayor had been synonymous with sex and celebrity. She hosted the local, raunchier version of reality show Big Brother, and entertained tabloids with a string of scandalous relationships. In public, she was brash and haughty. “If I’m honest,” she once lectured a radio host, “your problem is that you’ve got an inferiority complex — you know you’re not quite a star.”

With an army of fans and multi-million earnings, Ms Sobchak was in a place to judge.

That early Ms Sobchak was decidedly apolitical. She refused to criticise President Putin, who was a friend and colleague of her late father, and rumoured to be her godfather. But in 2011, something changed. Ms Sobchak began to wear the badge of a political activist. In December, she spoke at an opposition rally protesting the results of the Duma parliamentary elections. She began to date one of the leaders of the opposition movement, Ilya Yashin, with whom she has since split.

Authorities made the extent of their displeasure clear by raiding her home early in the morning of June 11, 2012; the masked, armed officers seized at least €2 million cash.

By that time, Ms Sobchak had already begun a new career as talk show host on TV Rain, the leading voice for liberal Moscow. Co-produced with the channel’s then editor-in-chief, Mikhail Zygar, Ms Sobchak’s shows were hugely popular. They were sharp and smart, and featured the newsmakers Russians wanted to see. With influence and connections that reached across the political spectrum, there were few people who could turn Ms Sobchak down.

The interview series has no doubt proved a useful testing ground for Ms Sobchak’s political career. But its roots go back much further than that — to 1989, and with the improbable union of two men: a 50-year democratic reformer called Anatoly and his former student, a 38-year old former KGB agent called Vladimir.

Then, St Petersburg mayor Anatoly Sobchak was touted him as a future national leader, second in popularity only to Boris Yeltsin. Vladimir Putin was Mr Sobchak’s loyal deputy and close confidante.

In the late 1990s, Mr Sobchak fell from grace and began to be hit with legal challenges and corruption allegations from opponents. He became ill from stress, and apparently on the verge of a heart attack. President Yeltsin refused to intervene to help his opponent, and legend has it, Mr Putin, then a Kremlin official, personally arranged a special operation to evacuate his former boss to Europe.

Mr Sobchak spent his final days in campaigning for Mr Putin’s presidency. In his last interview, taken in February 2000, just days before his death, he described Mr Putin as “a democrat, free marketeer and, also a man of government – decisive and brave.” Mr Putin returned the compliments: “I really like people like him. He’s real. We had very close, comradely relations, very trusting. I think I can call him an old comrade.”

At a press conference on 5 October, the president was asked what he thought about another Sobchak standing for office. He repeated his admiration for his former mentor, but refrained from endorsing a new Sobchak campaign. “It’s the first time I’ve heard that she wants to run,” he said. “I’m sure that there will be other candidates.”

Few doubt Ms Sobchak has at least checked in with the Kremlin about her campaign. On 14 October, BBC Russian Service reported that Ms Sobchak had recently met with Mr Putin. According to Ms Sobchak’s mother, the presidential hopeful had been recording a video about her father. Others suggested more was discussed. The business paper Vedomosti have reported “sources” in the presidential administration suggesting the Kremlin was “looking for a woman to run,” and that “Ksenia was ideal.”

A source close to the government told The Independent that the Kremlin understood Russia is not ready to endorse the idea of a female president. At the same time, it is widely assumed Ms Sobchak’s star appeal will energise an otherwise predictable election.

Whatever the details of any arrangement, the Kremlin’s response so far has contrasted obviously with the treatment of fellow opposition politician Mr Navalny, who remains in jail for his role in organising “unsanctioned” protests.

On Tuesday, Mr Navalny celebrated a legal victory with a preliminary judgment from the European Court of Human Rights. That ruling said the embezzlement trial that saw him and his brother convicted in December 2014 was unfair. The subsequent conviction was a technicality impeding Mr Navalny’s presidential bid. But the Head of Russia’s Central Election Commission Ella Pamfilova has since stepped in to declare that, regardless, he will be ineligible to stand until 2028.

The idea of Ms Sobchak’s candidacy has been divisive in Russian opposition circles. Navalny and Sobchak, once close colleagues, have fallen out over it. Mr Navalny himself described Sobchak as “the Kremlin’s ideal caricature liberal candidate.” Ms Sobchak took to Instagram to reply publicly, criticising Mr Navalny for “asserting a monopoly over the opposition.”

Ilya Yashin, opposition leader, and Ms Sobchak’s former boyfriend, told The Independent that Mr Navalny was the “only person with the popularity, the only person capable of running a campaign, and the only person running not for their image, but to win.”

Mr Yashin said his party would continue to support Mr Navalny’s campaign to get on the ballot paper.

“Without him, there are no elections,” he said.

Source: independent.co.uk

Ask me anything

Explore related questions