One million Muslims are being held right now in Chinese internment camps, according to estimates cited by the UN and U.S. officials. Former inmates—most of whom are Uighurs, a largely Muslim ethnic minority—have told reporters that over the course of an indoctrination process lasting several months, they were forced to renounce Islam, criticize their own Islamic beliefs and those of fellow inmates, and recite Communist Party propaganda songs for hours each day. There are media reports of inmates being forced to eat pork and drink alcohol, which are forbidden to Muslims, as well as reports of torture and death.

The sheer scale of the internment camp system, which according to The Wall Street Journal has doubled in China’s northwestern Xinjiang region just within the last year, is mindboggling. The U.S. Congressional-Executive Commission on China describes it as “the largest mass incarceration of a minority population in the world today.” Beijing began by targeting Uighur extremists, but now even benign manifestations of Muslim identity—like growing a long beard—can get a Uighur sent to a camp, the Journal noted. Earlier this month, when a UN panel confronted a senior Chinese official about the camps, he said there are “no such things as to centers,” even though government documents refer to the facilities that way. Instead, he claimed they’re just vocational schools for criminals.

China has been selling a very different narrative to its own population. Although the authorities frequently describe the internment camps as schools, they also liken them to another type of institution: hospitals. Here’s an excerpt from an official Communist Party audio recording, which was transmitted last year to Uighurs via WeChat, a social-media platform, and which was transcribed and translated by Radio Free Asia:

Members of the public who have been chosen for reeducation have been infected by an ideological illness. They have been infected with religious extremism and violent terrorist ideology, and therefore they must seek treatment from a hospital as an inpatient. … The religious extremist ideology is a type of poisonous medicine, which confuses the mind of the people. … If we do not eradicate religious extremism at its roots, the violent terrorist incidents will grow and spread all over like an incurable malignant tumor.

“Religious belief is seen as a pathology” in China, explained James Millward, a professor of Chinese history at Georgetown University, adding that Beijing often claims religion fuels extremism and separatism. “So now they’re calling reeducation camps ‘hospitals’ meant to cure thinking. It’s like an inoculation, a search-and-destroy medical procedure that they want to apply to the whole Uighur population, to kill the germs of extremism. But it’s not just giving someone a shot—it’s locking them up for months in bad conditions.”

China has long feared that Uighurs will attempt to establish their own national homeland in Xinjiang, which they refer to as East Turkestan. In 2009, ethnic riots there resulted in hundreds of deaths, and some radical Uighurs have carried out terrorist attacks in recent years. Chinese officials have claimed that in order to suppress the threat of Uighur separatism and extremism, the government needs to crack down not only on those Uighurs who show signs of having been radicalized, but on a significant swath of the population.

The medical analogy is one way the government tries to justify its policy of large-scale internment: After all, attempting to inoculate a whole population against, say, the flu, requires giving flu shots not just to the already-afflicted few, but to a critical mass of people. In fact, using this rhetoric, China has tried to defend a system of arrest quotas for Uighurs. Police officers confirmed to Radio Free Asia that they are under orders to meet specific population targets when rounding up people for internment. In one township, police officials said they were being ordered to send 40 percent of the local population to the camps.

The government also uses this pathologizing language in an attempt to justify lengthy internments and future interventions any time officials deem Islam a threat. “It’s being treated as a mental illness that’s never guaranteed to be completely cured, like addiction or depression,” said Timothy Grose, a China expert at the Rose Hulman Institute of Technology. “There’s something mentally wrong that needs to be diagnosed, treated—and followed up with.” Here’s how the Communist Party recording cited above explains this, while alluding to the threat of contagion:

There is always a risk that the illness will manifest itself at any moment, which would cause serious harm to the public. That is why they must be admitted to a reeducation hospital in time to treat and cleanse the virus from their brain and restore their normal mind. … Being infected by religious extremism and violent terrorist ideology and not seeking treatment is like being infected by a disease that has not been treated in time, or like taking toxic drugs. … There is no guarantee that it will not trigger and affect you in the future.

Having gone through reeducation and recovered from the ideological disease doesn’t mean that one is permanently cured. … So, after completing the reeducation process in the hospital and returning home … they must remain vigilant, empower themselves with the correct knowledge, strengthen their ideological studies, and actively attend various public activities to bolster their immune system.

Several other government-issued documents use this type of medical language. “This stuff about the poison in the brain—it’s definitely out there,” said Rian Thum, noting that even civilians tasked with carrying out the crackdown in Xinjiang speak of “eradicating its tumors.” Recruitment advertisements for staff in the internment camps state that experience in psychological training is a plus, Thum and other experts said. Chinese websites describe reeducation sessions where psychologists perform consultations with Uighurs and treat what they call extremism as a mental illness. A government document published last year in Khotan Prefecture described forced indoctrination as “a free hospital treatment for the masses with sick thinking.”

This is not the first time China has used medical analogies to suppress a religious minority. “Historically, it’s comparable to the strategy toward Falun Gong,” said Adrian Zenz, a researcher at the European School of Culture and Theology in Germany. He was referring to a spiritual practice whose followers were suppressed in the early 2000s through reeducation in forced labor camps. “Falun Gong was also treated like a dangerous addiction. … But in Xinjiang this [rhetoric] is certainly being pushed to the next level. The explicit link with the addictive effect of religion is being emphasized possibly in an unprecedented way.”

Tahir Imin, a U.S.-based Uighur academic from Xinjiang who said he has several family members in internment camps, was not surprised to hear his religion being characterized as if it’s a disease. In his view, it’s part of China’s attempt to eradicate Muslim ethnic minorities and forcefully assimilate them into the Han Chinese majority. “If they have any ‘illness,’ it is being Uighur,” he said. In addition to Uighurs, The Washington Post has reported that Muslim members of other ethnic groups, like the Kazakhs and the Kyrgyz, have been sent to the camps. “I think the Chinese government is saying: ‘This ideological hospital—in there, send every person who is not [ethnically] Chinese. They are sick, they are not safe [to be around], they are not reliable, they are not healthy people.’”

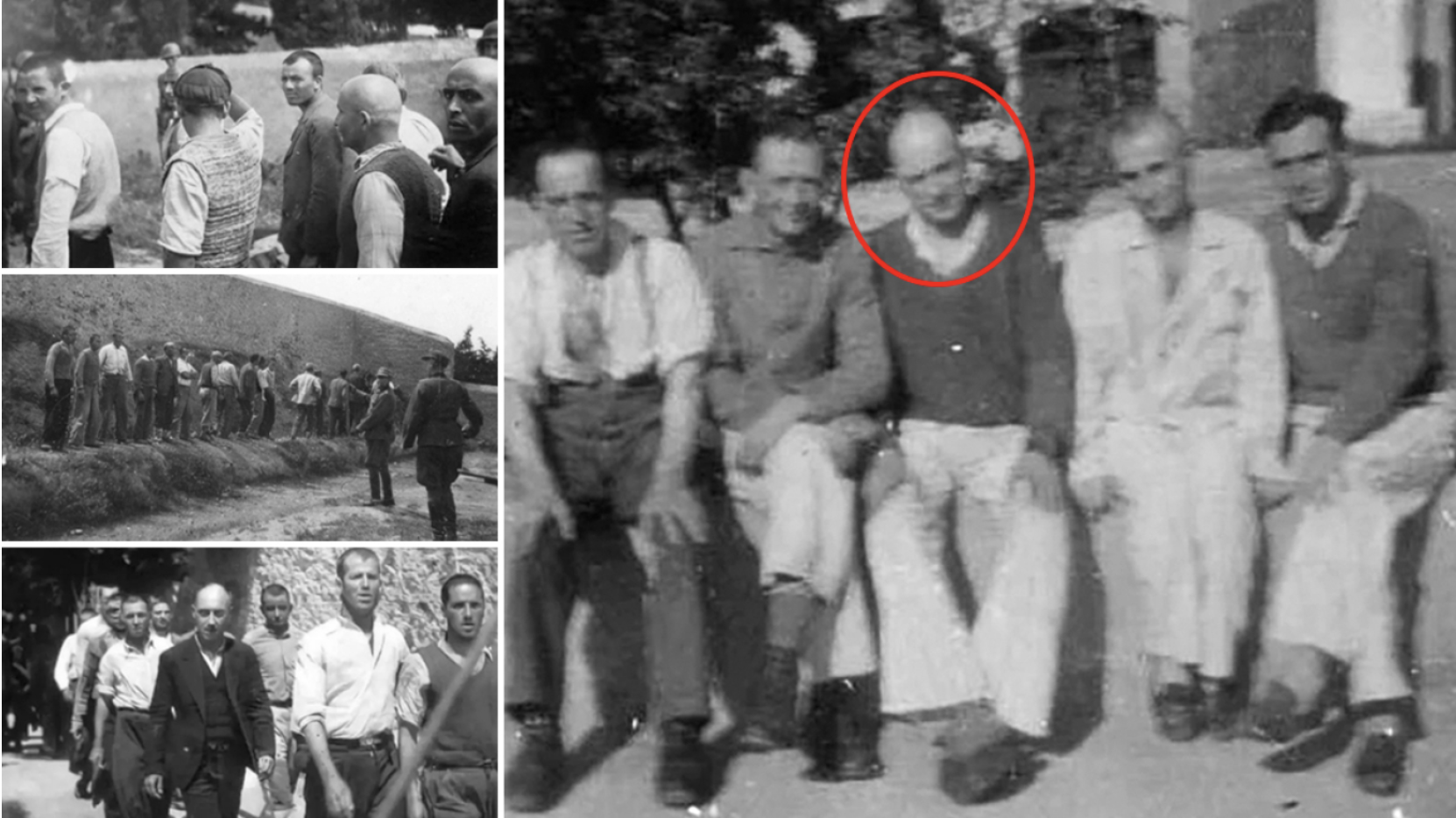

(The doors of mosques closed by authorities in Xinjiang)

The terrible irony is that in “treating” Uighurs for supposed psychological problems, China is causing very real psychological damage, both at home and abroad. One former inmate told The Independent he suffered thoughts of suicide inside the camps. And as Uighurs in exile around the world learn what is happening to their relatives back home, some have told reporters they suffer from insomnia, depression, anxiety, and paranoia.

Murat Harri Uyghur, a 33-year-old doctor who moved to Finland in 2010, said he has received word from relatives that both his parents are in the camps. He has launched an online campaign, “Free My Parents,” he said will raise money to start an advocacy organization to help them, but he told me he suffers from recurrent panic attacks. He also described finding himself prone to feelings of anger, powerlessness, and exhaustion. “I try to be normal,” he said, “but I have a psychological problem now.”

In an interview with The Globe and Mail, a Uighur woman in Canada who said she had a sister in the camps said, “I cannot concentrate on anything. My mind is off. I cannot sleep.” She added, “I lost a lot of weight because I don’t want to eat anymore.”

Some Uighurs I spoke to who are living abroad also have to cope with a pervasive sense of guilt. They know that Beijing treats any Uighur who’s traveled internationally as suspicious, and that their family members are treated as suspicious by association. For example, a 24-year-old Uighur attending graduate school in Kentucky, who requested anonymity for fear that China would further punish his relatives, said it’s been 197 days since he’s been able to contact his father in Xinjiang. He tracks the days on a board tacked to his bedroom wall. “I’m afraid for my dad’s life,” he said. Asked why he believes his father was sent to an internment camp, he replied without a trace of doubt: “Because I go to school here in a foreign country.”

“Now I know that if I ever go home,” he added, “I will be imprisoned just like my dad.”

Source: theatlantic

Ask me anything

Explore related questions