On November 1st, 1913, Sultan Mehmed the 5th resigned from every right of domination over the Great Ocean. Exactly one month later, Crete was officially incorporated into the Greek State.

It took almost a century of tears, blood and martyrdom for Cretans to rid of the Ottomans. But in sunny Chania on Sunday, December 1, 1913, it was time for vindication. In the presence of King Constantine and Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos, in a very festive atmosphere, Crete was now part of Greece and the blue and white flag was flew proud on top of the fortress of Firka, while 101 cannon shots were fired from Greek Navy warships.

The Ottomans conquered Crete in 1667. Although the whole period was one of a difficult and often bloody struggle, the last 90 years were the most difficult for all Cretans to bear because Greece, after enormous sacrifices following the Revolution of 1821, achieved independence from the Turkish yoke, but Crete remained under Sultan rule.

Even though Cretans fought for their independence as hard as mainland Greeks and made the same sacrifices, the Great Powers had prevented Crete from joining Greece and becoming part of the new Hellenic Nation.

Greece was recognised as a new nation at the signing of the “Protocol of London” on January 22, 1830, but Crete was left out of it. The island was caught in the middle of power politics between the Great Powers that were trying to take as much as they could from the slowly dying Ottoman Empire. Crete was given to the Regent of Egypt to administer in recognition of services provided to the Sultan during the Greek Revolution in Peloponnese.

The Egyptian administration lasted 10 years and it was a relatively quite period in comparison to the previous 10 years. This was primarily due to the Egyptian ruler’s long term plan to achieve permanent control of the island and did not want to give any cause to the Great Powers to interfere with the affairs of Crete during his administration period.

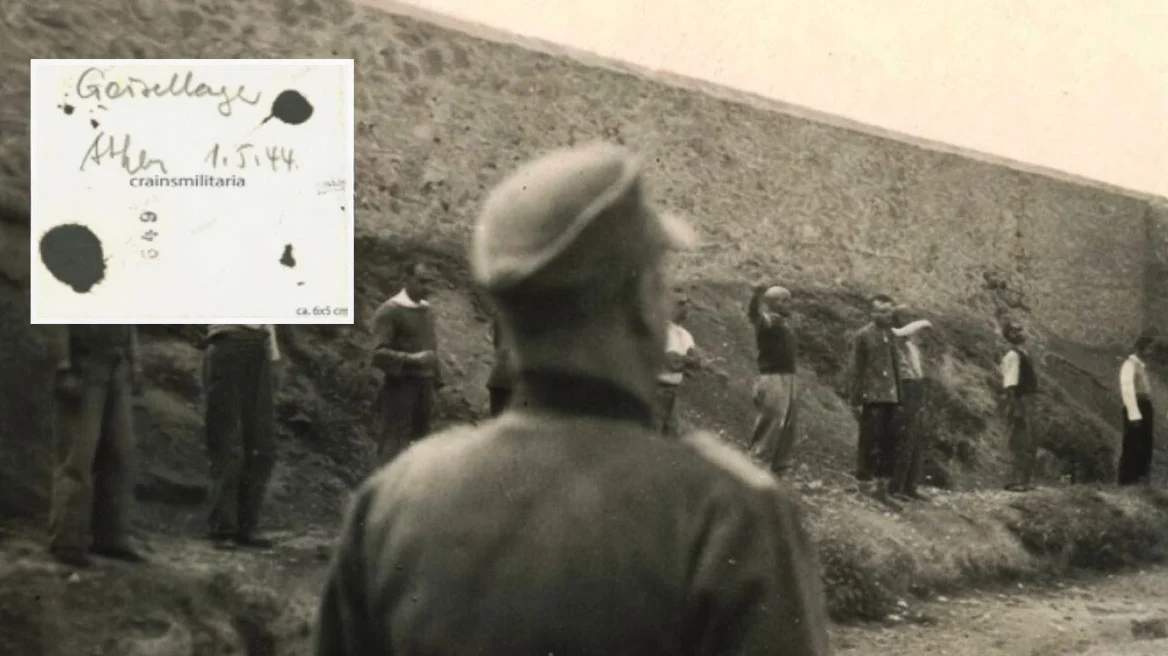

In 1833 there was an uprising but that was put down harshly and swiftly by the Egyptian troops that arrested and hung the leaders of the uprising. The war between the Regent of Egypt and the Sultan in Syria in 1840 and the defeat of the Egyptians put an end to the Egyptian administration of Crete. The Great Powers convened again and still being in favour of keeping the Ottoman Empire intact they signed a new “Treaty of London” in July 1840, ceding Crete from Egyptian control and bringing it again under direct Turkish control.

While that was happening a number of Cretan leaders who had been in exile in Greece, decided to return to Crete to organise a new uprising. Revolution was declared simultaneously in a number of places all over Crete on February 22, 1841. Unfortunately this uprising did not last long as Crete was not prepared for a long struggle. Greece was not in a position to help and the Great Powers were pressing for an end to the bloodshed. By April, many of the surviving rebels left the island for the safety of Greece and a long period in exile.

A number of other uprisings were to follow with the biggest one being the 1866 – 1869 revolt, during which Crete experienced one of the bloodiest and harshest periods of repression. The holocaust of the Monastery of Arkadi was to become a legend and an example of the type of sacrifices that Cretans were prepared to make in their struggle for freedom and for “Enosis”, union, with Greece.

Another Cretan uprising took place in 1897-1898 followed by more bloodshed and Ottoman atrocities in Chania in early 1898. Greece sends armed forces to the island, but the Great Powers turn against the Greek army and Cretan rebels. Yet, thanks to the heroic act of Spyros Kayales, who raised the Greek flag using his body as a pole, the Italian head of the Great Powers navy gives the order to stop bombarding Chania.

Now the Great Powers decide to give Crete autonomy, and on November 2 the last Turkish soldier left Cretan territory. Crete was placed under the protection of the Great Powers and only the Sultan’s high sovereignty. From 1898 to 1913 the Cretan State was founded, under Greek King George and a government of five Christians and a Muslim, as Muslims accounted for about 25% of Cretan population in 1900.

During that period, a dominant political force appeared, a young lawyer, Eleftherios Venizelos, who quickly came into conflict with King George. The “Revolution in Therissos” (March 10, 1905), organized by Venizelos, forced George to resign from his power in Crete. He was replaced by Greek politician Alexandros Zaimis. The main demand of the insurgents was the immediate union of Crete with Greece.

The victorious outcome of the Balkan Wars (1912-1913) for Greece, due to the insightful policy of Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos, has accelerated developments. On May 30, 1913, the Sultan of the Fellowship resigned all his rights to Crete by the Treaty of London (Article 4), and he withdrew from his Sovereignty on the island (November 1, 1913). Crete was free and its union with Greece was finally achieved.

Source: Philip Chrysopoulos/greekreporter

Ask me anything

Explore related questions