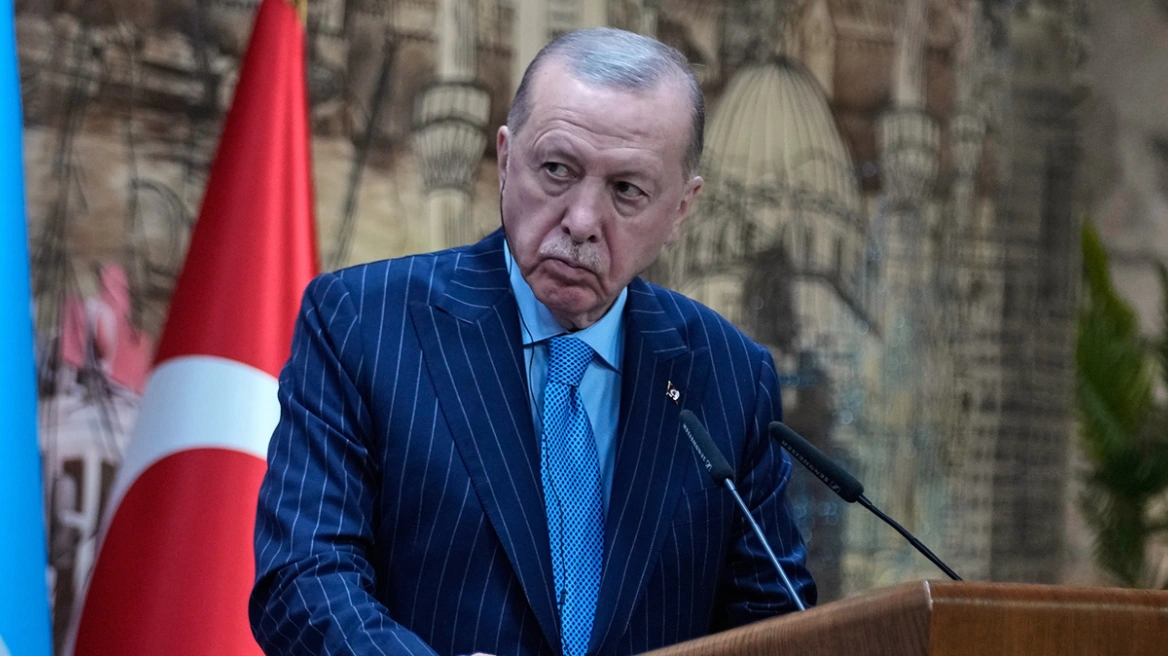

Modern Turkey arose nearly one hundred years ago against the backdrop of European efforts to divide the Anatolian Peninsula. This fact drives both Turkey’s collective paranoia and its xenophobia. Its nightmare is a Kurdish secession. While the PKK and its offshoot groups long ago abandoned this goal in favor of localized autonomy, Turkish president Recep Erdoğan’s penchant for instigating fights with neighbors and regional states may soon make Turkey’s fears a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Turkey’s problem with its Kurdish problem has existed almost as long as the Turkish Republic itself: Just two years after Turkey’s 1923 founding, Kurds rose up in the Sheikh Said rebellion in opposition to the abolition of the caliphate. In 1927, İhsan Nuri Pasha declared the Republic of Ararat, a small Kurdish state in far eastern Anatolia along the Iranian and Armenian borders. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, modern Turkey’s first president, ordered that entity crushed. Both the Turkish army and air force responded with brutal efficiency over the next three years. In 1936, another Kurdish rebellion erupted in Dersim in protest of forced Turkification and mandatory relocation in order to dilute demographically non-Turkish identities. Once again, the Turkish army crushed the uprising. In each case, Kurds could justify their uprisings in specific grievances beyond simply national identity, but their revolts simply reinforced the Turkish government’s distrust of any expression of Kurdish identity.

The Turkish government’s antipathy to Kurdish identity ossified after Atatürk’s 1938 death. Successive governments in Ankara ignored Kurdish-populated areas as they modernized Turkey’s economy. Turks accepted Kurds, but only when the Kurds foreswore their own ethnic and cultural identity.

Over subsequent decades, Turkey suffered its share of political instability. Some Kurds took part, but political violence usually occurred in the framework of left- versus right-wing extremists. It was in this context that the future Kurdistan Workers Party founding member (Partiya Karkerên Kurdistan, PKK) Abdullah Öcalan got his start. He eventually grew to resent the subordination of Kurds in the so-called class struggle and formed the PKK to rectify this. Öcalan officially launched the PKK insurgency in 1984, as often targeting rival Kurds as Turks.

Mitsotakis for Moria: Our priority is the health & safety of residents & immigrants

“Obviously, the controls at our maritime borders, which are also European, will continue”

The United States offered blind support to Turkey in its fight against the PKK. The PKK was a Marxist group and, in the Cold War context, that trumped everything. While both the PKK and supporters of its off-shoot groups in Syria might engage in historical amnesia, the group did also engage in brutality and terror inside Turkey. Curiously, it would be thirteen years—and against the backdrop of a Clinton-era arms sale—before the State Department would formally designate the group to a terrorist entity. It was an anti-climactic and perhaps even counterproductive action: Not only did its timing suggest motivations other than an objective assessment of terrorism, but the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War had also changed the group’s reality. Under President Turgut Özal, the Turkish government had begun to reform with an eye toward a deal. Özal’s premature death scuttled that effort, but Öcalan’s 1999 capture forced the group to move in new directions. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan himself authorized secret outreach in 2012, but ultimately broke off his talks after many Kurds in Turkey voted for the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) rather than his own Justice and Development Party (AKP). The Turkey-PKK peace process did have some success to show for its negotiators’ efforts: An interim agreement saw the PKK lay down their arms inside Turkey and many fighters move to Syria.

Read more: National Interest

Ask me anything

Explore related questions