Aubrey R. Paris, Ph.D.,Science and Technology Policy Adviser in the Office of the Science and Technology Adviser to the U.S. Secretary of State (STAS) at the U.S. Department of State, wrote an interesting piece on Heritage Science, the discipline “that bridges science and culture” and we all need to read it.

The cinematic universe is ripe with fictional treasure hunters capable of quenching any moviegoer’s thirst for adventure. Fans of satchels and chase scenes may gravitate toward the classic Indiana Jones. Lara Croft offers an exciting film-video game crossover. And those who read this piece on blockchain might guess (correctly) that my personal favorite is Benjamin Franklin Gates of National Treasure fame. While their personalities differ, these characters have in common a passion for cultural heritage and, paradoxically, an undisputed ability to make heritage scientists cringe.

Heritage science is a truly interdisciplinary field that bridges science and culture. It combines the life sciences, physical sciences, engineering, and humanities to research and understand all aspects of cultural heritage. As early as 1843, scientist Michael Faraday indirectly described the field while lecturing about environmental factors that contribute to the degradation of leather book binding. Today, heritage science revelations appear in scientific journals, museums, libraries, and your favorite action flick (with creative liberties taken in the latter, of course).

Conservation of art, architecture, and other artifacts is an important component of heritage science—and one that movies often fail at portraying. In those movies, our heroes are practically villains when they carry ancient relics through death-defying stunts or paint lemon juice onto centuries-old parchment. But in real-life, environmental factors like light, heat, and humidity are the villains that permanently damage artifacts. Analytical methods ranging from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to infrared spectroscopy are used to understand how artifacts were made and identify which treatments or protective measures will minimize degradation.

As artifacts are discovered and conserved, heritage scientists also play a role in their interpretation, which employs scientific tools to assign dates and provide context. For instance, the nuclear science technique of carbon-14 dating can determine the age of objects up to 50,000 years old. In National Treasure 2: Book of Secrets, spectral imaging helps Benjamin Franklin Gates learn the context of a 140-year old diary page. If Indiana Jones unearths an intact crypt, the objects he finds within will be contemporaneous with one another. These are all examples of cultural heritage interpretation.

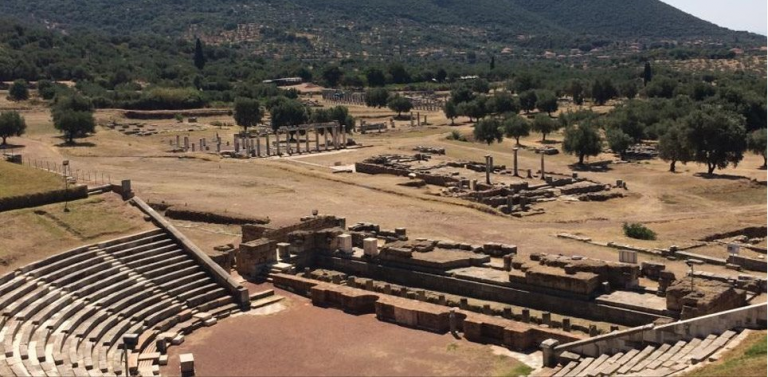

A third aspect of heritage science is management, or finding ways to ensure that sites, artifacts, and other objects can be simultaneously protected and appreciated now and in the future. With proper management, public engagement can increase understanding of cultural heritage. In fact, public engagement is arguably the one aspect of heritage science that Indiana Jones, Lara Croft, and Benjamin Franklin Gates get right, since their antics tend to boost interest in archaeology, culture, and history.

Progress in heritage science depends on developing new and improved methods for conservation, interpretation, and management. Good techniques are effective yet minimally invasive, since damage in the name of discovery is still damage. In other words, we do not want to accidentally explode a 200-year old ship (à la National Treasure) or leave behind a pile of architectural ruins (per the Lara Croft video game). Jokes aside, it turns out that finding non-destructive analytical methods can be challenging. Another challenge is collaborating across the myriad disciplines involved in the field, which include archaeology, art, biology, chemistry, ethics, history, philosophy, physics, sociology, and more.

When these challenges are overcome, major cultural, educational, and economic benefits follow suit. Heritage science helps people discover, understand, and appreciate their roots and, at the community level, informs decisions about the present and future. The knowledge provided by the field is shared broadly by museums and cultural heritage sites, which promote tourism while increasing respect for other cultures. Heritage science can even facilitate discoveries in other scientific fields, as evidenced by the identification of previously unknown bacterial species found in untouched caves.

The significance of these impacts has been—and continues to be—recognized throughout the U.S. Government. The State Department facilitates conservation when historical sites are threatened, engages in conversations about the role of cultural heritage in advancing foreign policy, and has even supported programs that have unearthed new discoveries. Other government agencies are developing new analytical tools, outlining goals for the advancement of cultural heritage preservation and access, and continuing to find helpful ways to engage as the field advances.

All things considered, it’s okay to have a love-hate relationship with fictional treasure hunters. They’re really good at being really bad heritage scientists, yet they still increase our appreciation for cultural heritage. What could you learn from heritage science today?

Source: US State Department

Ask me anything

Explore related questions